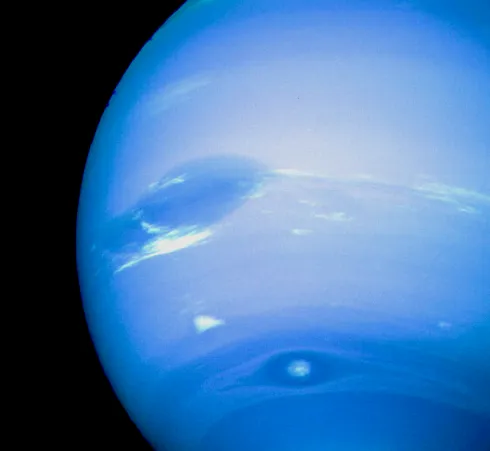

Storms on Neptune seen by the Voyager probe, which flew by the planet in 1989. Credit: NASA/JPL

By Brian Sheen

Neptune is the Solar System’s outermost planet, so far from the Sun that it takes almost 164.8 Earth years for it to travel once round around it. The 4.5 billion km that separate Neptune and the Sun is some 30 times greater than the Earth-Sun distance.

With all its twists and turns, the story of Neptune’s discovery reads like the work of a Victorian novelist.

The British side of the story had the Cornish mathematician John Couch Adams (pictured left around 1846) working away by candlelight in his remote farmhouse, calculating the position of a new and unknown planet from the ‘wobbles’ in Uranus’s orbit – perturbations caused by the influence of another massive body.

Meanwhile, across the Channel, experienced astronomer Urbain Le Verrier had also been asked to solve the problem of Uranus’s irregular orbit by the director of the Paris Observatory.

Back in Britain, Adams’s results were passed to Astronomer Royal George Biddell Airy, who subsequently replied asking for some confirmation. But the Astronomer Royal never received an answer from Adams.

However, a draft reply from Adams was recently discovered in the Cornwall Records Office. The reason this was never posted may have something to do with Adams believing that Airy’s question was trivial.

This is supported by Airy’s textbook on gravitation, which Adams had already read. Since it confirmed what Airy was asking about, Adams assumed that Airy didn’t need a response.

The British drive to find Neptune stalled. Those involved rested on the knowledge that the Paris Observatory did not have a telescope big enough to find the planet, even if they knew where to look.

The spell of procrastination was broken when Airy got news of Le Verrier’s accurate predictions for Neptune’s position. The Astronomer Royal asked James Challis to search for Neptune at the Cambridge Observatory.

But, on the continent, Le Verrier had sent his results to astronomer Johann Galle at the Berlin observatory. With good fortune, Le Verrier’s letter arrived on the director’s birthday, with a clear night and no Moon.

In an accommodating mood, director Johann Encke gave permission for Galle to undertake observations following Le Verrier’s letter, and using a new, unpublished map, he found Neptune within the hour.

The observations made by Challis were not an entirely wasted effort. Adams used the results to calculate the true distance between Neptune and the Sun, as well as the planet’s mass. And, just 17 days after Galle’s discovery of Neptune in Berlin, William Lassell used his large reflector to find its largest moon, Triton.

Lidcott Farm near Launceston, Cornwall, birthplace of John Couch Adams. Credit: Brian Sheen

Brian Sheen is a retired research chemist and director of the Roseland Observatory in Cornwall. A Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society, he became interested in John Couch Adams after he discovered two memorials to the astronomer in St Sidwell’s church, Laneast. He continues to research Adams’s life using local records to uncover details about his childhood and later astronomical work.