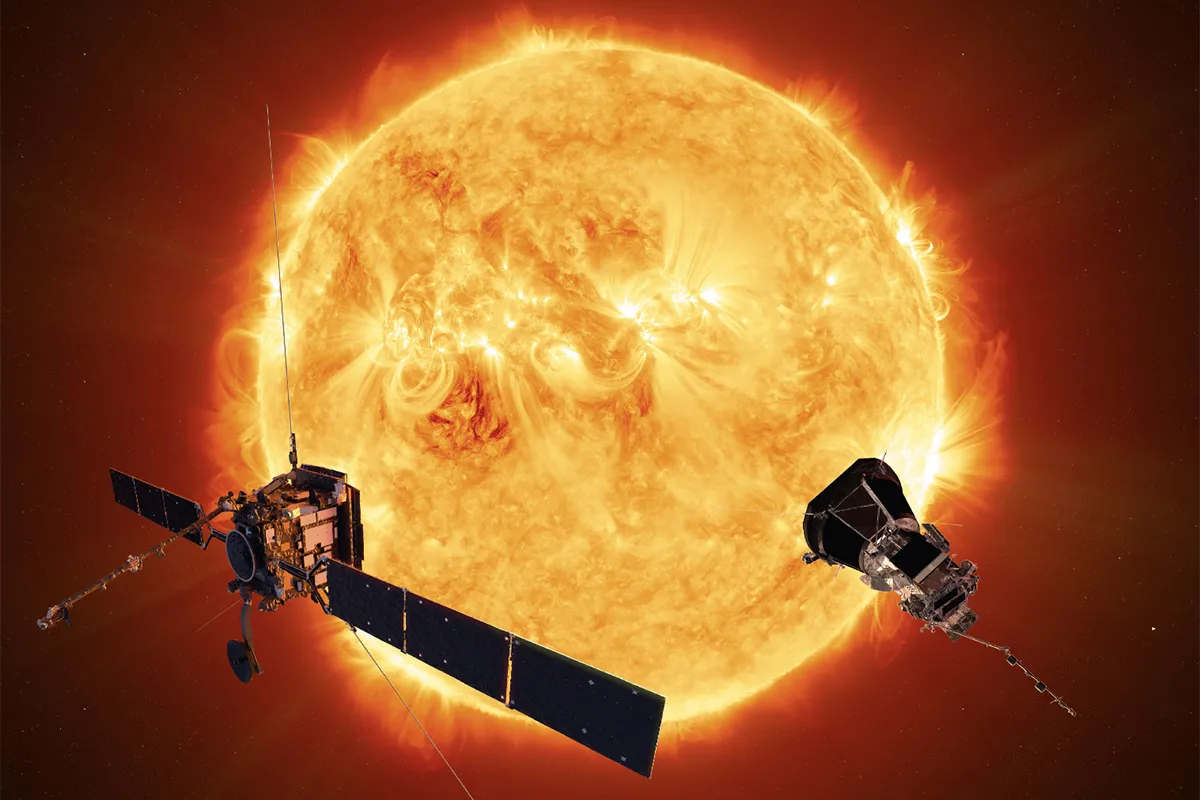

On Christmas Eve 2024, the Parker Solar Probe made its closest approach to the Sun so far.

The NASA spacecraft passed just 6.1 million km (3.8 million miles) from the Sun’s surface during its closest approach, known as perihelion, breaking the record for the closest humanity has ever past by the Sun.

While the Sun’s radiation would fry most spacecraft, Parker is specially designed to not only withstand the heat, but take measurements of the Sun’s atmosphere.

The flyby’s timing couldn’t be better, as the Sun is currently at or near solar maximum, the peak of its activity – mission controllers at NASA are hoping the spacecraft could be directly hit by a solar flare during one of its flybys.

“No human-made object has ever passed this close to a star, so Parker will truly be returning data from uncharted territory” says Nick Pinkine, Parker Solar Probe mission operations manager at the Applied Physics Laboratory, where the mission is operated from.

What is the Parker Solar Probe?

The Parker Solar Probe launched on 12 August 2018 from Cape Canaveral.

Its highly elliptical orbit takes it as far out as the orbit of Venus, before turning back and diving in close to the Sun.

The extreme orbit takes 88 days to loop around the Sun and serves two purposes.

Firstly, it allowed Parker to make gravitational assist manoeuvres by flying close to Venus, stealing a small part of its momentum to accelerate.

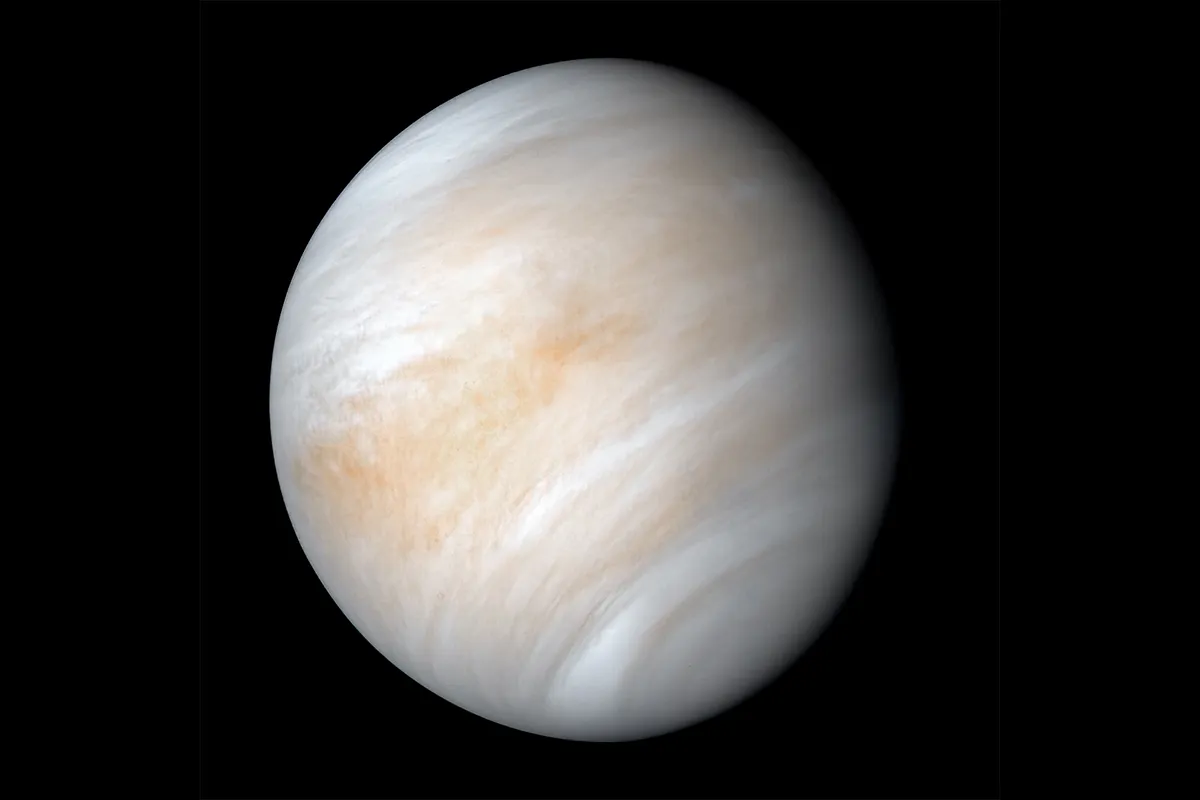

On 6 November 2024, the Parker Solar Probe made its seventh and final flyby of Venus, passing just 376km (233 miles) from the planet’s surface.

The manoeuvre accelerated the spacecraft to 692,000 km/h (430,000mph), making Parker the fastest human made object ever made.

Secondly, the elliptical orbit allow Parker to fly in very close to the Sun, but only for short periods.

During the Christmas Eve flyby, the Parker Solar Probe will be subjected to temperatures of around 980ºC (1,800ºF), as well as intense radiation.

It can survive as the spacecraft is equipped with an 11.5cm (4.5 inch) carbon composite shield that protects it from the Sun’s heat and radiation, but even this can only withstand the extreme environment for a limited time.

While this limits the length of each observation, by spending most of its orbit in a cooler more comfortable part of space, Parker has been able to conduct its mission over a much longer span of time.

The Christmas Eve 2024 flyby of the Parker Solar Probe

On 24 December 2024 at 11:53am UTC, the Parker Solar Probe undertook its Perihelion 22, passing just 6.1 million km (3.8 million miles) from the Sun’s ‘surface’, around nine times the Sun’s diameter.

To put this into perspective, if the distance between Earth and the Sun were a metre stick, the probe would be just 4cm away.

The flyby coincides with the peak of the Sun’s 11-year cycle of rising and falling activity, when the Sun releases solar flares more frequently.

The radiation from these flares can easily damage the electronics of spacecraft, as happened to Japan’s Hayabusa asteroid mission in 2003, while astronauts on the International Space Station have to take shelter when a bit flare passes by Earth.

So it’s unusual that Parker’s operators are actually hoping the spacecraft will be hit by a big flare, so it can take measurements of the event.

Though other spacecraft are also keeping an eye out for potential flares, we won’t know if the spacecraft got ‘lucky’ for several days, as the spacecraft goes out of contact with Earth for several days during perihelion to fully concentrate on taking data.

As the close pass is occurring when the spacecraft is on the other side of the Sun from Earth, we won’t know if it got ‘lucky’ for several days.

The spacecraft is due to transmit a ‘beacon tone’ on 27 December 2024, letting NASA know everything is alright, but won't transmit science data home until the new year.

"This is one example of NASA’s bold missions, doing something that no one else has ever done before to answer longstanding questions about our universe," says Arik Posner, Parker Solar Probe program scientist at NASA Headquarters. "We can’t wait to receive that first status update from the spacecraft and start receiving the science data in the coming weeks."

The science of the Parker Solar Probe

The Parker Solar Probe is braving the extreme conditions close to the Sun in an attempt to better understand our star, and by extension other stars as well.

The spacecraft is flying through a region known as the corona – the atmosphere of the Sun – which is normally only visible from Earth during a solar eclipse.

The corona is responsible for heating and accelerating the particles of the solar wind, and Parker is aiming to discover more about how this process works.

Strangely, while the surface of the Sun is a ‘mere’ 5,600ºC (10,100ºF), the corona can reach up to one million ºC (1.8 million ºF) and discovering why is one of Parker’s key science goals.

Fortunately, Parker doesn’t have to worry too much about the high temperatures as the corona isn’t very dense – it’s similar to how you can put your hands in the oven to get out the Christmas turkey without getting burnt, even though the air molecules are at 180ºC.

The solar wind can impact electronic equipment in space and power grids here on the ground, meaning understanding how it works has practical applications on Earth as well.

What comes next for the Parker Solar Probe after the Christmas Eve flyby

After the Christmas Eve 2024 flyby of the Sun, the Parker Solar Probe will continue to make close passes of the Sun.

On 19 June 2025, it will conduct Perihelion 24, its third closest pass of the Sun, completing its primary mission.

After this the probe will continue to loop around the Sun, but as it’s 6 November flyby of Venus nudged Parker within the planet’s orbit, it will not be able to perform another gravitational assist to adjust its orbit.

The spacecraft will occasionally have to fire its thrusters, as the solar wind is constantly pushing against it. Without correction, the spacecraft will drift out of alignment with Earth and be unable to transmit data home.

Eventually, the thrusters will run out of fuel. When this happens, mission controllers plan on ordering the spacecraft to flip around, exposing its delicate underbelly to the Sun’s radiation for the first time.

While this means most of the spacecraft will burn away, the carbon heatshield will survive and will continue to orbit the Sun for potentially a billion years – a lasting testament to the robustness of NASA engineering.