It is possible for disappearing islands to float on the methane seas of Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, a new study has found.

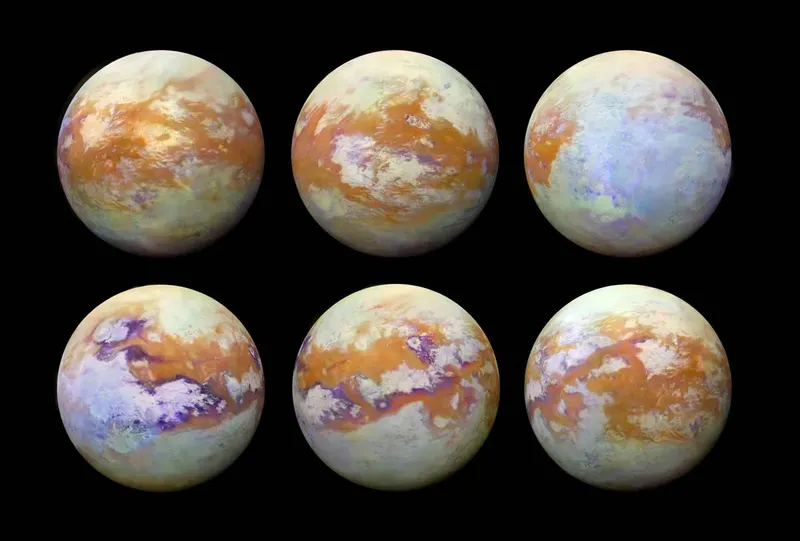

Titan is a remarkable place, and on paper matches many of the properties of our own planet Earth.

Titan is the only moon in our Solar System with an atmosphere.

Of all the worlds in our Solar System, including the planets, it is the only place other than Earth that's know to have liquid flowing on its surface: seas, lakes and rivers.

These bodies are not filled with liquid water, but instead liquid hydrocarbons like methane and ethane.

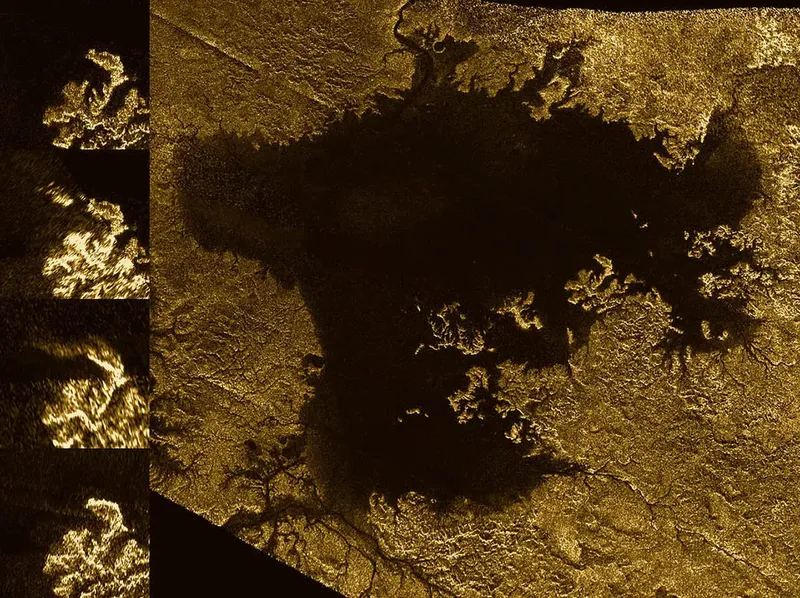

The largest seas on Titan stretch down hundreds of feet, and are hundreds of miles wide.

Previous studies found that Titan's lakes boast winds similar to Earth.

A new study found that islands of organic material may be floating on Titan's liquid lakes, before disappearing.

In 2014, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft spotted bright, transient dots in the moon’s seas, called ‘magic islands’.

“I wanted to investigate whether the magic islands could actually be organics floating on the surface, like pumice that can float on water here on Earth, before finally sinking," says Xinting Yu, from the University of Texas at San Antonio, who led the study.

"For us to see the magic islands, they can’t just float for a second and then sink. They have to float for some time, but not for forever either."

Yu’s team determined that any organics that rained down from the atmosphere wouldn’t immediately dissolve.

If these clumps had the right amount of porosity, it would be possible for them to float on the seas.

The clumps could amass near the shore, then break off to form the islands.