NASA has been officially tasked with establishing a standard time-zone on the Moon, Coordinated Lunar Time (LTC), in a memo issued by the White House’s Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP).

LTC will be tied to Co-ordinated Universal Time (UTC) which is used as the global standard here on Earth.

However, Moon-time will need to differ as the effects of relativity means that time actually runs differently there.

Why does the Moon need its own time-zone?

“Time passes differently in different parts of space,” says Steve Welby, deputy director for National Security at the OSTP.

“For example, time appears to pass more slowly where gravity is stronger, like near celestial bodies – and as a result the length of a second on Earth is different to an observer under different gravitational conditions, such as on the Moon.”

As Earth has 81 times the mass of the Moon, time appears to run slightly slower on our planet. To an observer on the Moon, an Earth-based clock would appear to lose 58.7 microseconds every Earth-day, or one second every 46 Earth-years.

While this would make no difference to humans, it has a huge impact on machines operating at the Moon.

They require precise timing to stay in formation and correctly align their communications arrays.

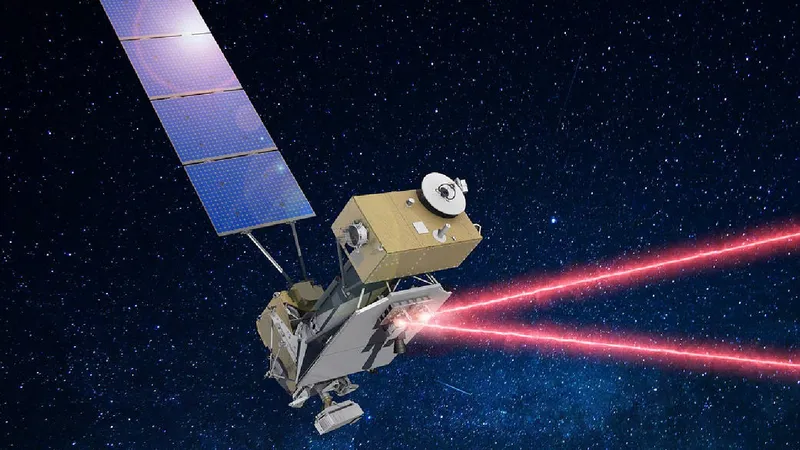

One example of a potential issue is spacecraft using range-finding – bouncing lasers off an object, then using the return time to calculate the distance.

If two spacecraft attempted to dock where one was running on Earth time and the other on lunar time, the discrepancy could cause them to disagree about their distance resulting in them missing each other or even crashing.

A similar problem effects GPS satellites, which differ by around 7 nanoseconds per day compared with Earth.

Return to the Moon

The need for a standard time-zone on the Moon has become a much more pressing issue, as recent years have seen a surge of renewed interest in the Moon.

In 2009, Chandrayaan-1 first found signs of water at the lunar south pole – not only was the discovery scientifically important, it is a potential resource for future space exploration.

Since then, there has been a great number of missions to the Moon (with varying degrees of success), with many more planned in the coming years.

The largest of these projects is NASA’s Artemis programme, which aims to return humans to the lunar surface for the first time in over 50 years. The first human landing mission currently scheduled for September 2026.

Such a mission will require a large amount of collaboration with international partners and private companies. All of these will need to operate to the same clock to ensure operations run smoothly.

“A consistent definition of time among operators in space is critical to successful space situational awareness capabilities, navigation, and communications, all of which are foundational to enable interoperability across the US government and with international partners,” says Welby.

China has also mounted several successful missions to the lunar surface.

The nation aims to send Chinese taikonauts to the Moon’s surface in the 2030s and has increasingly been seeking international collaboration to achieve its lunar aims.

With so many missions planning on operating in and around the Moon, it is more important than ever to ensure that they are co-ordinated to avoid accidents and ensure the safe return of their data.