This year’s solar maximum has been a remarkably lacklustre event, leading to fears that our star may be heading towards a long-term slump in activity.

However, the latest research shows that the current lull may just be part of the natural peaks and troughs within the Sun’s cycle.

Activity on the surface goes through a cycle lasting around 11 years.

The number of sunspots on the surface rises and falls as the solar magnetic field flips its poles, throwing the material inside the Sun into turmoil.

The peak of our current cycle was due to happen in 2012/13, but arrived a year late, over this winter.

When it did arrive, the maximum saw some of the lowest activity ever recorded.

- For more on this, read Lucie Green's guide to the science of the solar cycle.

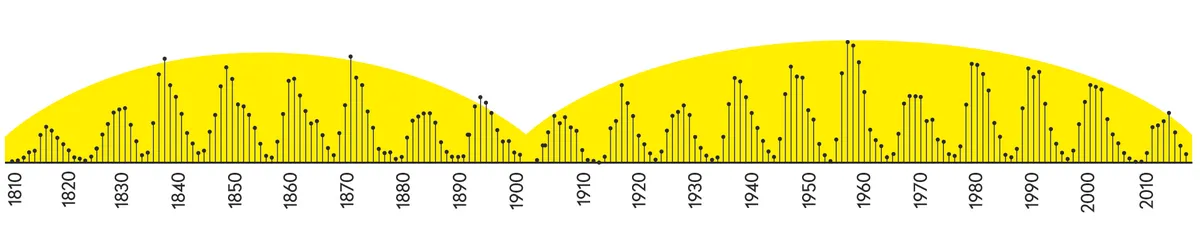

The number of sunspots recorded was half that of 2002, the previous cycle’s peak. It is the lowest level of activity since Solar Cycle 14, which ran from 1906 to 1913.

There have been some suggestions that the Sun is heading towards a global minimum, exhibiting consistently low activity for several cycles in a row.

These lulls can have knock on effects on Earth’s climate leading to colder temperatures.

Between 1645 and 1715, our star went through a long period of inactivity, known as the Maunder Minimum, where hardly any sunspots were recorded.

Experts were concerned that this year’s cycle was the beginning of another such minimum.

The Earth won't freeze

But Yale University’s Dr. Sarbani Basu from Yale University suggests otherwise.

Speaking at the 224th AAS Meeting in Boston, she was keen to point out that records of sunspot activity over the last 400 years show that the there have been several dips in activity that have lasted only one or two cycles.

Whilst sunspot numbers are the lowest for any maxima in living memory, they are not that extreme when compared with previous dips.

The slump appears to stem from the fact that the magnetic field around the Sun was low after the last cycle’s maximum.

The solar magnetic field is the main driver of the solar cycles, and as the results of a maximum can take over 17 years to fully dissipate, the effects are still being felt.

Researchers will be studying the Sun even more closely over the coming years to predict how this low maximum will affect the next.

With dozens of specialist observatories observing every aspect of the Sun, researchers hope to learn more about the Sun’s long term activity and help make better predictions in the years to come.