The James Webb Space Telescope has detected carbon dioxide at Jupiter's icy moon Europa.

The discovery has major implications for the possibility that Europa could potentially support life.

Europa is one of Jupiter's Galilean moons, and previous research has shown that beneath its icy crust lies a salty ocean of liquid water.

Icy moons with subsurface oceans like Saturn's Enceladus, which was studied by the NASA Cassini mission, are important places in the Solar System in the search for habitability.

Now, Europa has been found to have a carbon source in studies of the icy moon using the James Webb Space Telescope.

The study shows that the carbon likely originated in the subsurface ocean, rather than being delivered by meteorites or other sources.

And the study also suggests that the carbon was deposited relatively recently.

Where is the carbon on Europa?

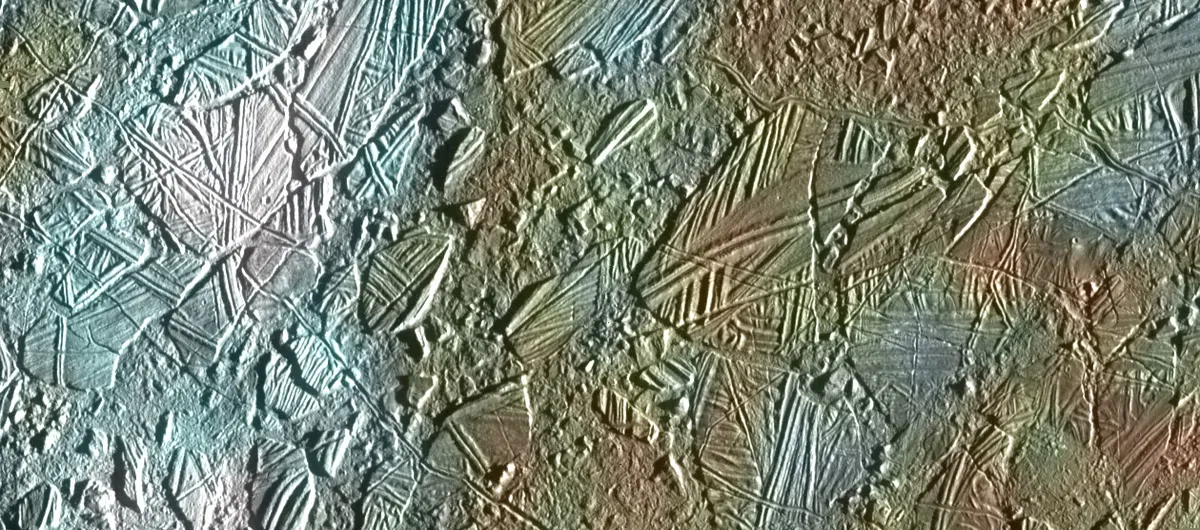

Studies using the Webb Telescope revealed that carbon dioxide is most abundant on Europa in a region called Tara Regio.

This is a geologically young area of resurface terrain known as 'chaos terrain'.

This means that in this region the icy surface has been disrupted, and that there could have been interplay of material between the surface and the liquid ocean below.

How the carbon dioxide was found

The researchers used data captured by Webb’s Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) instrument.

The instrument gathered spectra from the surface of Europa, allowing the teams to locate specific chemicals at the icy moon.

The carbon dioxide found by NIRSpec isn't stable, which the scientists say shows it was probably deposited on a geologically recent timescale.

This is further inferred given the carbon dioxide's concentration in a region of young terrain.

Key takeaways

Previous studies of the icy moons of the Solar System have concentrated on the fact that some of these bodies have liquid oceans beneath their frozen crusts.

Because liquid water is a key ingredient for life as we know it on Earth, moons like Enceladus and Europa are potentially habitable, and may even be able to support microbial life.

This latest revelation that Europa also contains carbon - which has likely originated from the subsurface ocean itself - is important because carbon is an element needed for life.

“On Earth, life likes chemical diversity – the more diversity, the better. We’re carbon-based life. Understanding the chemistry of Europa’s ocean will help us determine whether it’s hostile to life as we know it, or if it might be a good place for life,” says Geronimo Villanueva of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, lead author of one of two independent papers describing the findings.

“We now think that we have observational evidence that the carbon we see on Europa’s surface came from the ocean. That's not a trivial thing. Carbon is a biologically essential element,” adds Samantha Trumbo of Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, lead author of the second paper analysing the data.

What next?

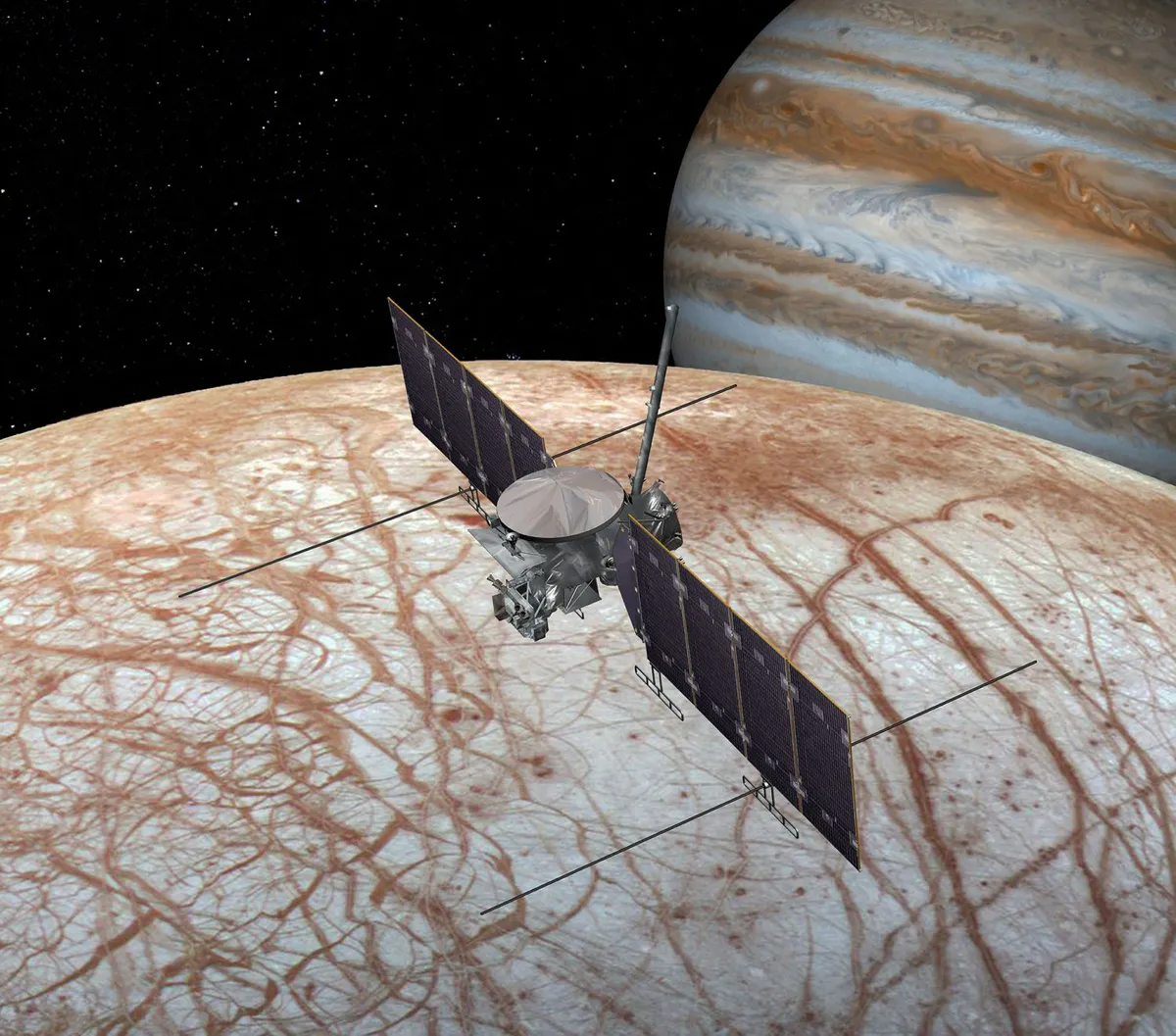

Future missions to Jupiter's icy moons are planned, like NASA's Europa Clipper spacecraft and the European Space Agency's JUICE mission.

Europa Clipper, which is due to launch in October 2024, will perform dozens of close flybys of Europa, gathering information about its potential habitability.

ESA's JUICE mission launched in April 2023 and is currently on its way to the Jovian system.

“Previous observations from the Hubble Space Telescope show evidence for ocean-derived salt in Tara Regio,” says Trumbo.

“Now we’re seeing that carbon dioxide is heavily concentrated there as well. We think this implies that the carbon probably has its ultimate origin in the internal ocean.”

“Scientists are debating how much Europa’s ocean connects to its surface. I think that question has been a big driver of Europa exploration,” said Villanueva.

“This suggests that we may be able to learn some basic things about the ocean’s composition even before we drill through the ice to get the full picture.”

Plumes on Europa?

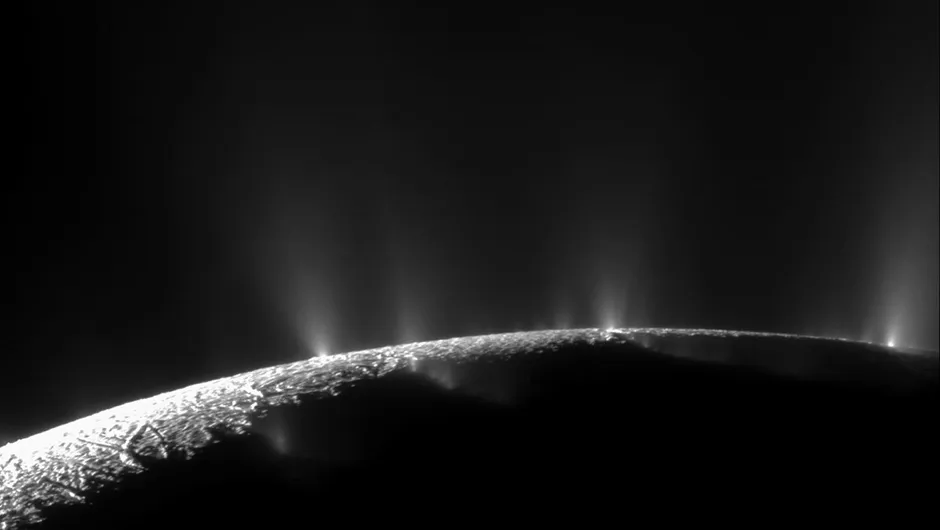

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SSI

One of the key revelations of the Cassini mission at Saturn was evidence of plumes erupting from beneath the surface of moon Enceladus.

In fact, the Cassini spacecraft was even able to make plume dives, analysing the material erupting from Enceladus into space.

In June 2023, scientists studying Cassini data found phosphorous, a key ingredient for life, at Enceladus.

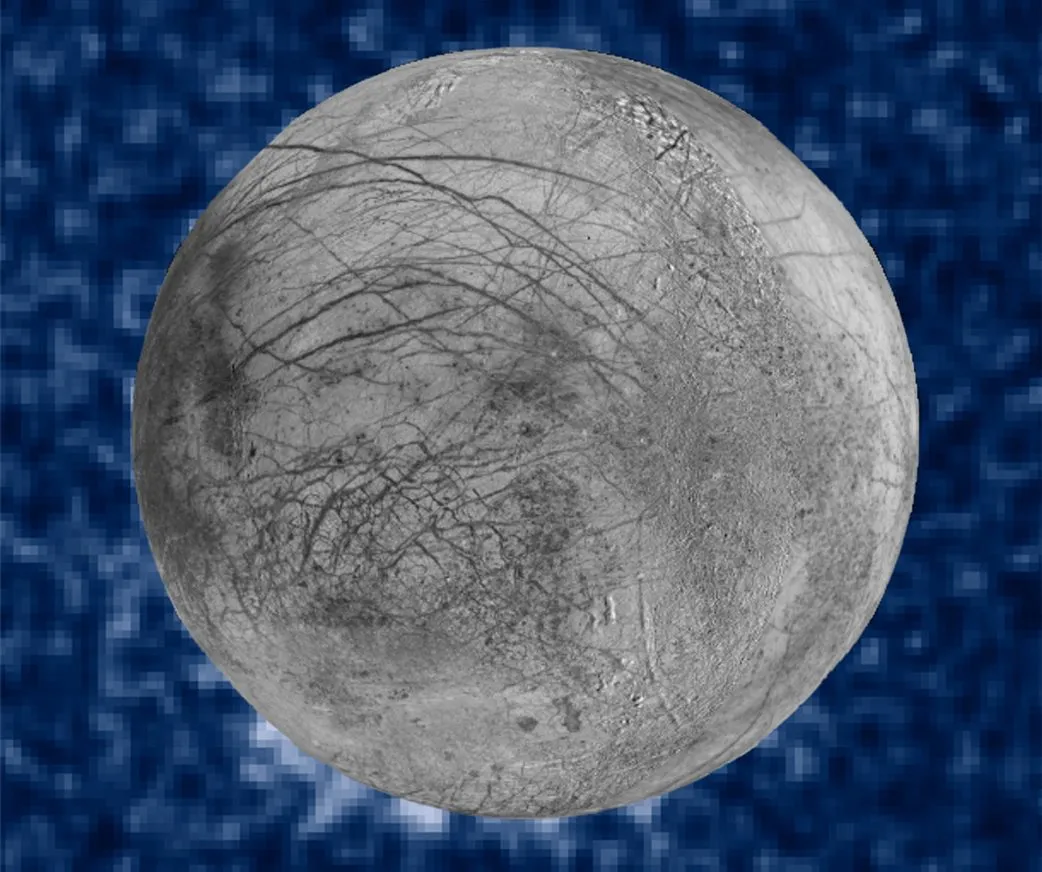

And observations with the Hubble Space Telescope have previously detected possible evidence of plumes at Europa.

Credits: NASA/ESA/W. Sparks (STScI)/USGS Astrogeology Science Center

So has Webb detected similar plumes at Europa?

For the time being, no.

Villanueva’s team say they looked for evidence of a plume of water vapour erupting from Europa, but weren't able to find conclusive proof.

“There is always a possibility that these plumes are variable and that you can only see them at certain times," says Hammel.

"All we can say with 100% confidence is that we did not detect a plume at Europa when we made these observations with Webb."