Will the James Webb Space telescope be able to detect signs of life one day, either in our own Solar System or elsewhere in the Galaxy?

When it comes to detecting carbon-based chemicals in the atmospheres of other planets, it seems no telescope can match the James Webb Space Telescope.

Carbon-based chemicals form the building blocks of life, and Webb is helping to track their distribution both within our Solar System and beyond, as shown in two recent discoveries.

Four questions James Webb Space Telescope is poised to answer

Webb's discovery at Europa

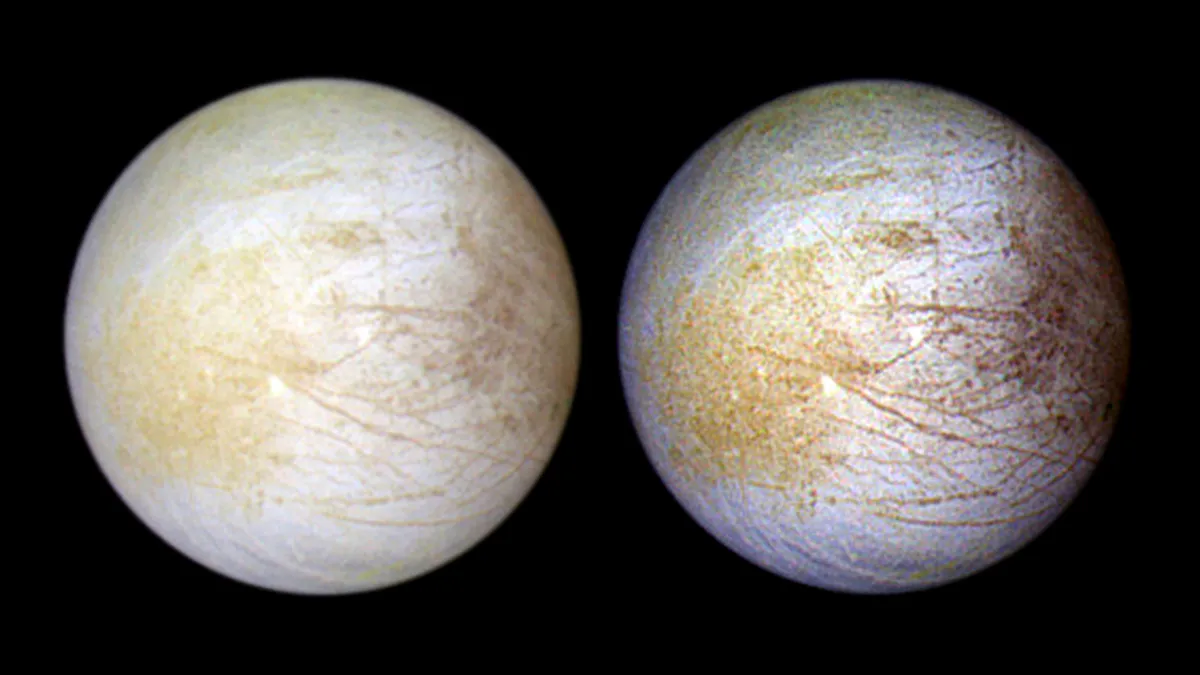

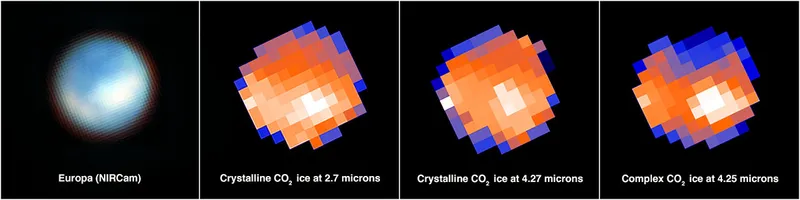

Beneath the icy crust of Jupiter’s moon Europa lies a saltwater ocean, one of the few places in our Solar System that could potentially be habitable.

The region of Europa called Tara Regio – a yellowish area of ‘chaos terrain’ – offers a unique way to glimpse the subsurface ocean.

Its jumble of geological features appear to indicate the surface ice is interacting with the ocean below.

When James Webb Space Telescope looked at Tara Regio, it found signs of carbon dioxide.

As this gas is unstable and the terrain is geologically young, it must have been deposited relatively recently, and most probably came from the ocean rather than an external source.

"We now think that we have observational evidence that the carbon we see on Europa’s surface came from the ocean," says Samantha Trumbo from Cornell University, who led one of two studies on the region.

"That’s not a trivial thing," she adds. "Carbon is a biologically essential element."

Carbon at exoplanet K2-18b

We know that the Webb Telescope is revealing active exoplanet atmospheres, and the discovery at Europa came a few weeks after big announcement.

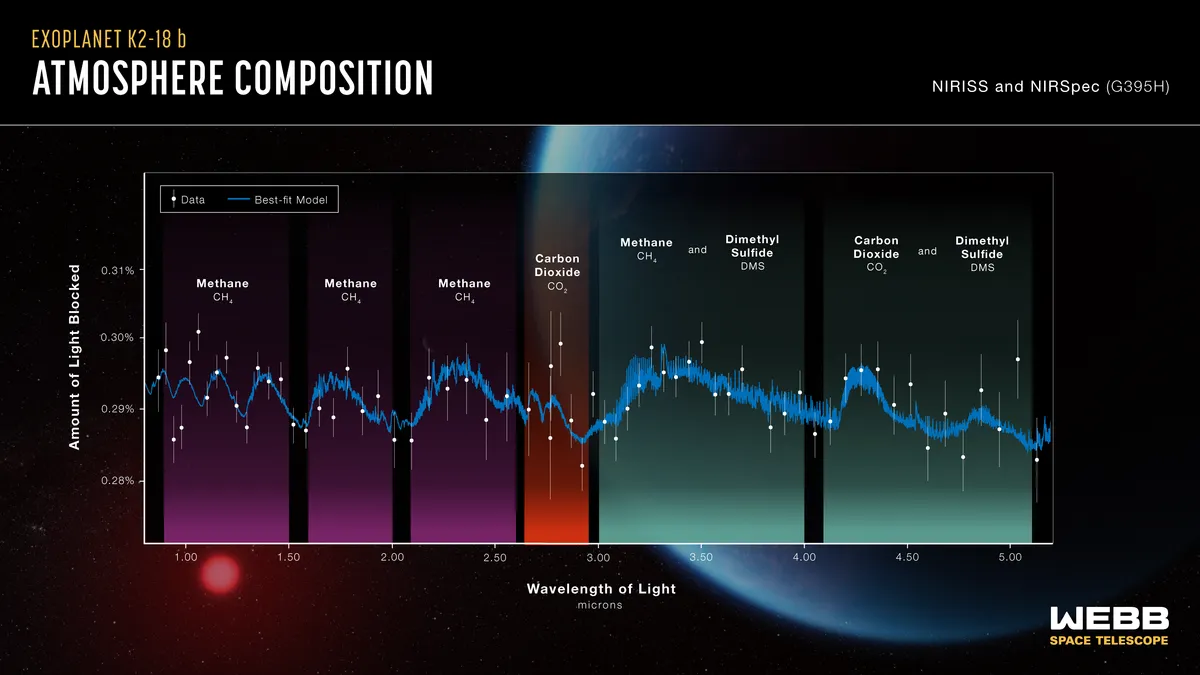

Another team revealed Webb had managed to detect not only carbon, but also a potential life signature in the atmosphere of an exoplanet.

K2-18b is around 2.6 Earth radii, making it sub-Neptune size, and sits within the habitable zone of its red dwarf star, where liquid water can potentially pool on the surface.

JWST detected clear signs of both carbon dioxide and methane on the planet, as well as a tantalising hint of dimethyl sulphide (DMS).

On Earth, DMS is only produced by life and the bulk of it found in our atmosphere is created by tiny marine algae known as phytoplankton.

The detection is currently very tenuous, though, and will require further validation.

"Upcoming [JWST] observations should be able to confirm if DMS is indeed present in the atmosphere of K2-18b at significant levels," says Nikku Madhusudhan from the University of Cambridge, who led the study.

Despite the uncertain nature of the find, Madhusudhan is hopeful of what the signal could mean.

"Our ultimate goal is the identification of life on a habitable exoplanet, which would transform our understanding of our place in the Universe."

Given the recent discoveries, the idea that Webb might one day detect life beyond Earth doesn't seem too much of a stretch.