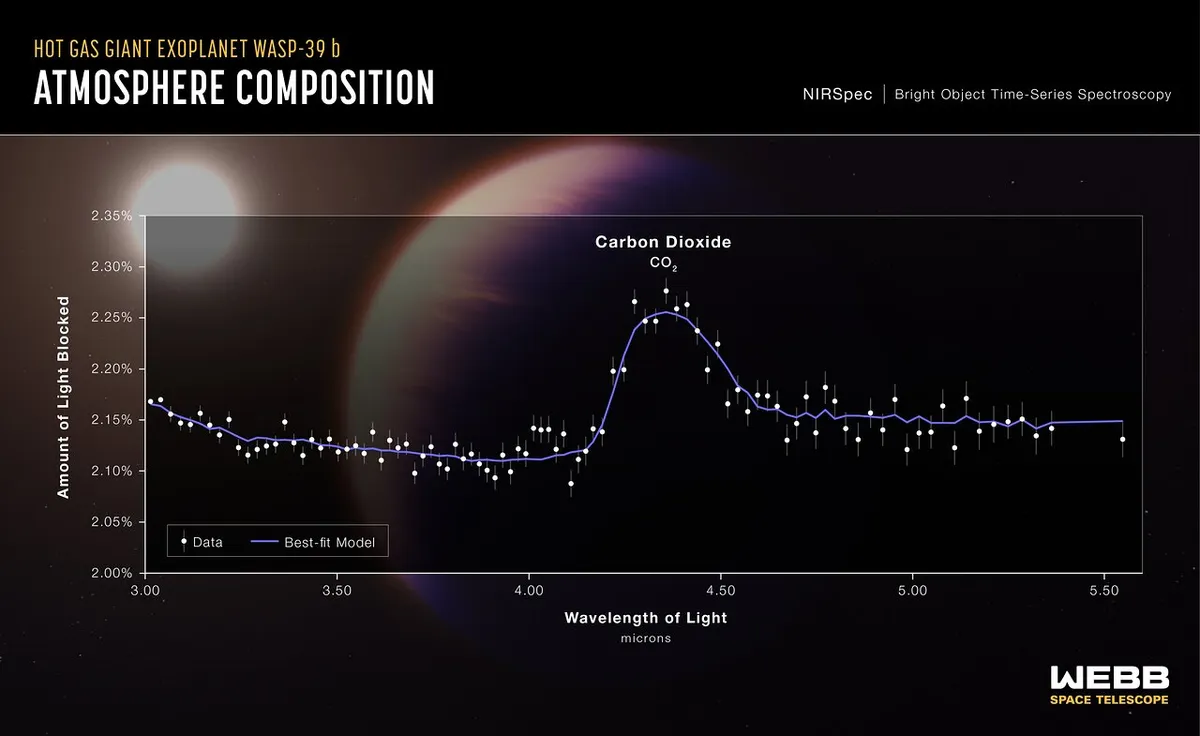

Carbon dioxide has been sniffed out for the first time in the atmosphere of a world beyond our Solar System by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

The gas is a key tool in understanding how planets grow and evolve, and is a potential biomarker that could point the way to finding life on other worlds.

The discovery was made at exoplanet WASP-39b, a gas giant 700 lightyears from Earth.

The planet is 1.3 times the diameter of Jupiter, but only a quarter of its mass.

For more on the science, read our guide to how James Webb Space Telescope will observe exoplanets.

It’s atmosphere has been greatly puffed up as it is extremely close to its star, meaning the atmosphere is superheated to around 900ºC.

When the planet passes in front of its star, some of the starlight we see passes through its atmosphere, and interacts with the chemicals in the air.

This leaves behind a signature in the light. It’s only a tiny change, but JWST is sensitive enough to be able to see it.

"As soon as the data appeared on my screen, the whopping carbon dioxide feature grabbed me," says Zafar Rustamkulov, from the Johns Hopkins University who helped with the study.

"It was a special moment, crossing an important threshold in exoplanet science."

JWST is the first telescope that’s able to look at the right wavelengths of light (3 to 5.5 microns) to pick out the signature of water, methane and carbon dioxide – all of which are vital to understanding how planet’s grow and evolve over time.

"Carbon dioxide molecules are sensitive tracers of the story of planet formation," says Mike Line from Arizona State University.

"By measuring this carbon dioxide feature, we can determine how much solid versus how much gaseous material was used to form this gas giant planet.

"In the coming decade, Webb will make this measurement for a variety of planets, providing insights into the details of how planets form and the uniqueness of our own Solar System."

But perhaps most interestingly, carbon dioxide is given off by forms of life here on Earth, including us humans, meaning it could be a biomarker.

"Detecting such a clear signal of carbon dioxide on WASP-39 b bodes well for the detection of atmospheres on smaller, terrestrial-sized planets," says Natalie Batalha of the University of California at Santa Cruz, who led the study

These types of planets are thought to be much more likely to hold life – or at least, a form of life we would be able to recognise as such – than planets like WASP-39b, raising hopes that we could be on the path to finding extra-terrestrial life.

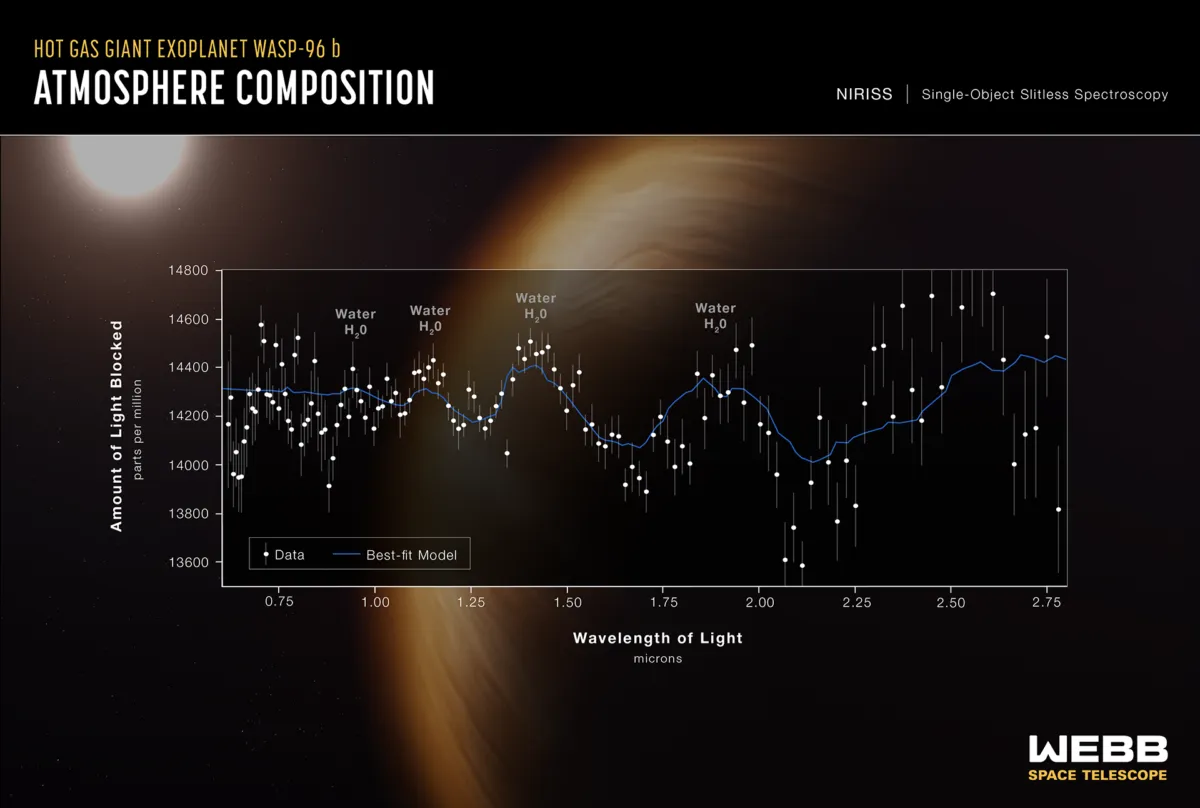

Though it has only been generating data for a few short months, JWST has already shown itself to be the next great instrument in exoplanet research.

"Over the last few decades the Hubble Space Telescope has been setting the precedent for what mysteries these atmospheres contain, from clouds scattering obscuring molecular features, to detections of water vapour absorption, and escaping atmospheres," says Hannah Wakeford from University of Bristol.

"Webb will complement and extend these studies with higher resolution, wavelength coverage, and precision to reveal the key trends in the data pointing to the formation and evolution of these planets."