On 18 March 1965 at 08.34 UT, viewers in Europe and Russia stared at their TVs in astonishment as 30-year-old cosmonaut Alexei Leonov climbed out of his Voskhod-2 spacecraft orbiting above Earth and became the first person in history to perform a spacewalk.

As far as the world was concerned, Leonov’s 12 minutes and 9 seconds floating outside the capsule – setting up and waving to a film camera that recorded the moment for posterity, tethered all the while by a 5m umbilicus – meant the Soviets were once again ahead of the US in the Space Race.

But it nearly wasn’t so, and it was only decades later that the death-defying drama of this historic mission came to light.

Read more about human spaceflight:

- What are the biggest dangers on the International Space Station?

- The history of the Soyuz rocket

- How will humans survive the journey to Mars?

Initial problems arose during pre-launch testing when Kosmos 57, an unmanned prototype sent to space to test the Soviet’s new spacesuit and airlock systems, self-destructed in orbit.

Nonetheless, just 3 weeks later the Voskhod-2 mission launched from Baikonur cosmodrome with Leonov and mission command pilot Pavel Belyayev on board.

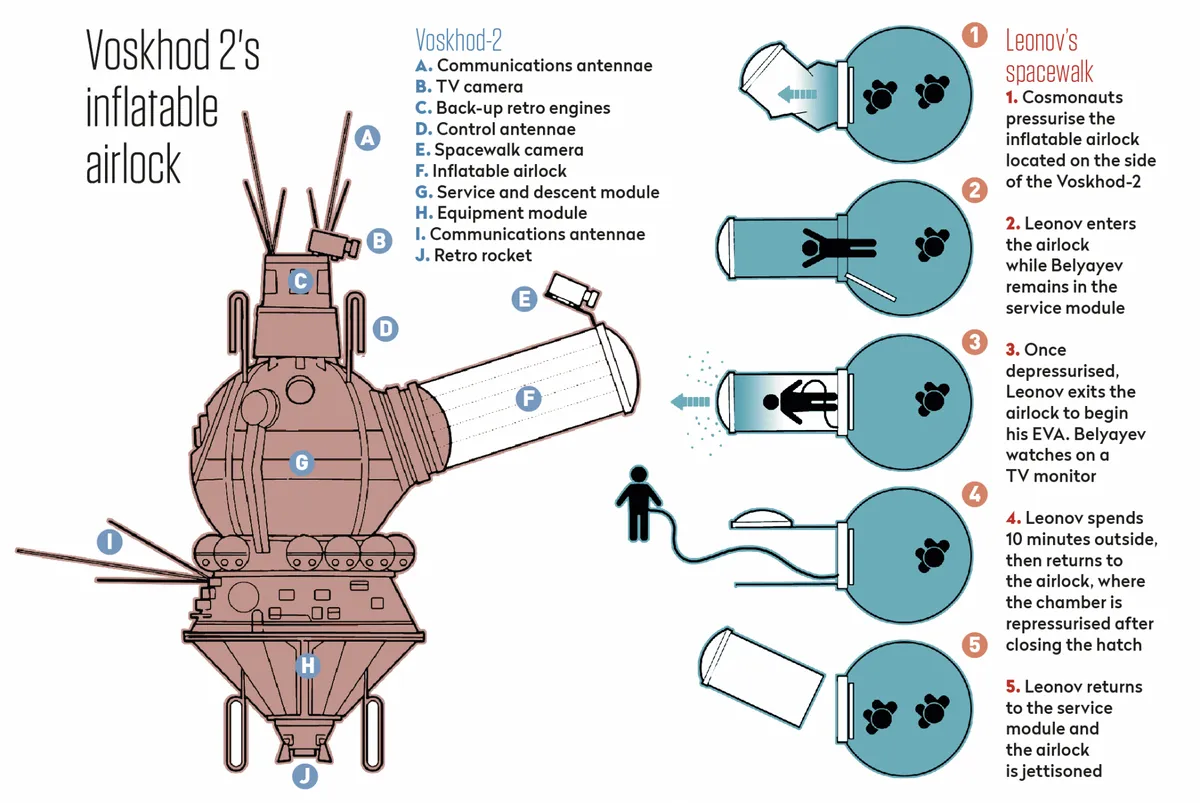

Once Voskhod-2 had completed its first Earth orbit, Leonov donned his life support backpack, while Belyayev deployed the Volga airlock, a 2.5m inflatable structure that had been designed, built and tested in 9 months.

After some final checks, Leonov climbed through the airlock’s hatch and shut the door. Exiting the second hatch, he activated the film camera and, safely tethered, floated into the void of space.

Leonov marvelled at the dynamic, “gigantic colourful map” of Earth below him. After 10 minutes, Belyayev called him to return, conscious that they were approaching Earth’s night side and would soon be plunged into darkness.

But Leonov’s spacesuit had expanded due to the lack of atmospheric pressure and his hands and feet now floundered inside.

Unable to grab the tether or fit through the hatch, he opened one of the suit’s valves, purposely depressurising it and risking oxygen starvation.

Sensing the difficulties, mission control cut the TV transmission.

Leonov re-entered the airlock head first, sweating profusely and fighting the symptoms of decompression sickness, but the airlock was designed for a feet-first entry so the outer hatch could be closed by hand.

Already exhausted in his bulky suit, Leonov now had to turn around in the narrow shaft to seal the hatch.

The crew found themselves in a Siberian forest, the habitat of bears and wolves. They jumped out of the capsule into snowdrifts.

At last he was back in the capsule. Respite, however, was brief. To the cosmonauts’ dismay, the descent module’s hatch wasn’t airtight and a slow leak caused the automated systems to release more oxygen into the capsule. One rogue spark would be enough to cause a fatal explosion.

To make matters worse, the automatic guidance system that prepared the spacecraft for re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere malfunctioned. The cosmonauts would have to do it manually, orientating the craft and firing the retro rockets right at the first attempt.

Leonov held Belyayev steady as he leant across the seats to check Voskhod-2’s alignment using the awkwardly positioned orientation porthole.

The cosmonauts scrambled back to their seats to rebalance the spacecraft for re-entry, but the delay between the two actions would land them hundreds of kilometres off-target.

As Voskhod-2 descended through Earth’s atmosphere, it began to tumble. The descent module had not separated from the equipment module, and Leonov and Belyayev endured intense gravitational loads.

At 100km, the modules separated. Finally, the descent module landed.

The crew found themselves in a Siberian forest, the habitat of bears and wolves. They jumped out of the capsule into snowdrifts.

Leonov recalled that, “after so many emergencies, the relief at drawing breath on Earth again was indescribable”.

Four hours later, a civilian helicopter located them. More aircraft attempted a rescue, but without success.

Supplies were dropped – clothes, food and a bottle of cognac – but most ended up caught in trees (the cognac smashed). As darkness fell, the temperature dropped to –5°C.

The following day, a rescue party on skis arrived with provisions, erected a hut and built a fire. After a second night, the cosmonauts and the group skied 9km cross-country to a helicopter that, at last, returned them to Baikonur.

Five years later Belyayev would be dead at just 44 from peritonitis. Leonov went on to be chief cosmonaut and then deputy director of the Cosmonaut Training Centre until his retirement in 1992.He died in October 2019.

Their story is one of danger met with courage and determination. These days, six-hour spacewalks may be routine aboard the ISS, but it was Leonov who took that incredible first step.

Nisha Beerjeraz-Hoyle is the space exploration editor of Popular Astronomy and a fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society. This article originally appeared in the March 2020 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.