On 14 November 1969, the skies were grey over Florida as the crew of Apollo 12 readied to launch to the Moon. It was raining, it was windy, and the weather was getting worse.

Though the crowd that had gathered on the coast was far smaller than the one for Apollo 11, there was one vital person in the audience – President Richard Nixon.

Whether his presence or the threat of a month-long delay until the next launch window pushed them on, the mission controllers decided to launch despite the bad weather.

Read more:

- Everything you need to know about Apollo 11

- A guide to the Apollo missions

- Podcast: Apollo 12, volcanic moons and cannibal galaxies

At 11:22am local time, the Saturn V bearing Charles ‘Pete’ Conrad, Alan Bean and Richard Gordon launched and began to climb into the overcast sky.

36 seconds later, a flash of white light surrounded the rocket. Inside the cockpit, dozens of warning lights lit up at once.

Though the crew had run through every imaginable failure scenario during training, none of them had ever seen so many fault alerts activated at once.

16 seconds after the first flash, a second one hit. The lights on the instrument panel went dead.

“I don’t know what happened here,” Commander Conrad called into Mission Control. “We had everything in the world drop out!”

Conrad had just a few minutes to decide whether to abort the mission. Despite everything, Apollo 12 was still flying in the right direction, and so he waited, his hand hovering over the abort control.

The rocket’s data was a garbled mess, but it was a garbled mess that – back at Mission Control – John Aaron, the environmental control engineer responsible for the ship’s electrical systems, recognised.

A year before, he’d seen the same error during a training exercise. He’d taken the time to track down the problem and, more importantly, worked out how to fix it.

“Try SCE to AUX,” he said, directing them to switch the Signal Conditioning Equipment, which translated between the spacecraft’s instruments and its displays, to the auxiliary back-up.

The crew had just a few moments to track down the obscure switch among the hundreds on the control panel.

Fortunately, lunar module pilot Alan Bean knew exactly where it was. He flicked the

switch and the panel lit back up. The mission was saved.

Realising that the spacecraft had been struck by lightning, Conrad jokingly requested that NASA “do a little more all-weather testing” before the next mission.

His jovial reaction to near disaster was typical of the Apollo 12 crew.

The trio were well known around NASA for being the tightest knit of all the Apollo crews, acting more like brothers than colleagues.

For the next three days, the crew laughed and joked their way through their tasks as they journeyed onwards to the Moon.

On 18 November, the crew arrived in lunar orbit. Conrad and Bean prepared to make their landing, leaving Richard Gordon to orbit in the command module, named Yankee Clipper.

Although Apollo 11 had come down just 4km from its target landing site, the flight planners were certain they’d learned enough to now make a landing with pinpoint accuracy.

Whoopee! Man, that may have been a small one for Neil, but that’s a long one for me.

Apollo 12 Commander Charles ‘Pete’ Conrad Jr

They were so confident that they decided to visit an old friend – the Surveyor 3 robotic lander, which had scouted the site in 1967.

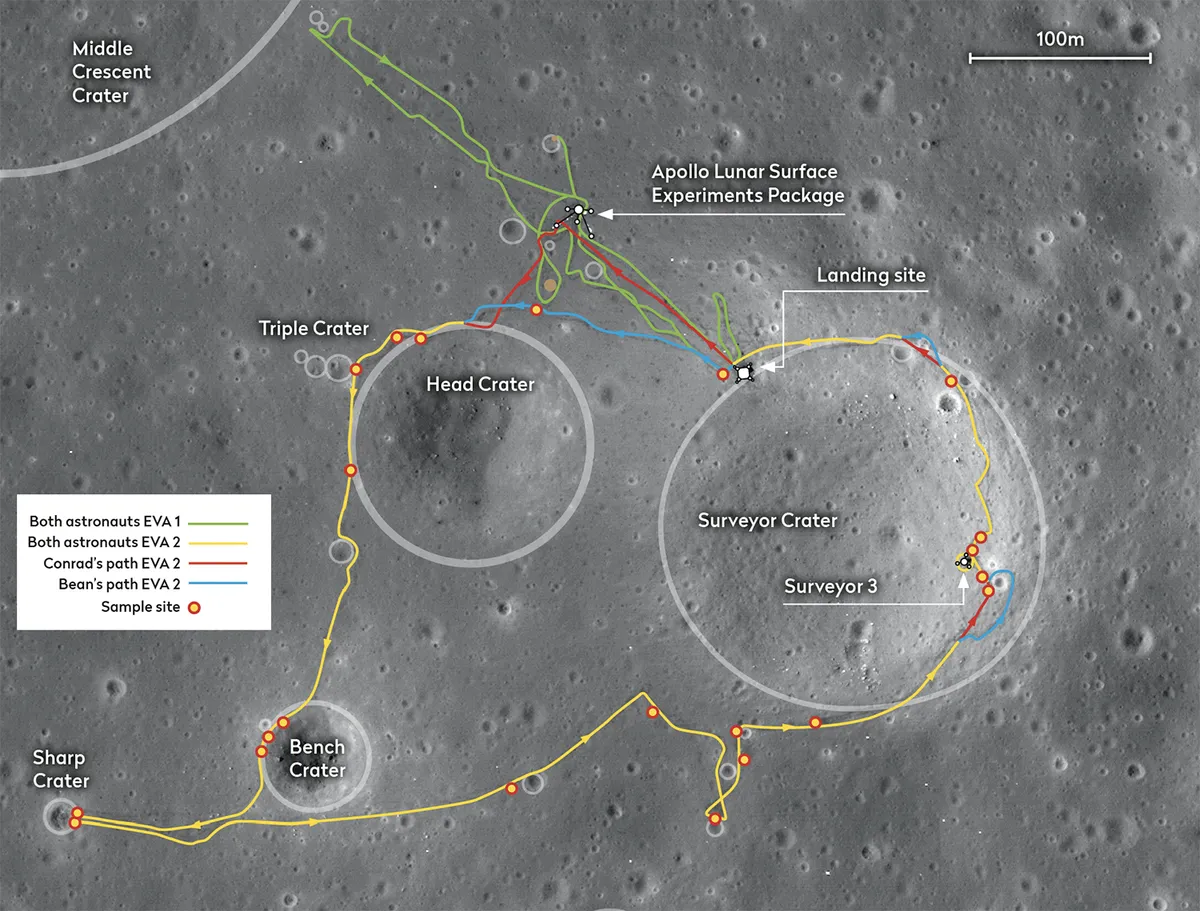

Confidence paid off and the pilots managed to bring down the lunar module, Intrepid, just 182m away from Surveyor 3.

After a short rest, it was time to exit onto the surface, though the occasion was slightly more irreverent than Apollo 11’s had been.

“Whoopee!” Conrad shouted as he reached the lunar surface. “Man, that may have been a small one for Neil, but that’s a long one for me.”

Conrad’s boisterousness, however, extended into how he walked across the lunar surface, and he soon earned the dubious honour of becoming the first person to fall over on the Moon.

Fortunately for him, the incident wasn’t captured on film. Unfortunately for the rest of the world, this was because the pair had destroyed the colour TV camera that was supposed to broadcast their moonwalk.

During set up, the camera had accidentally been pointed at the Sun, destroying its sensor.

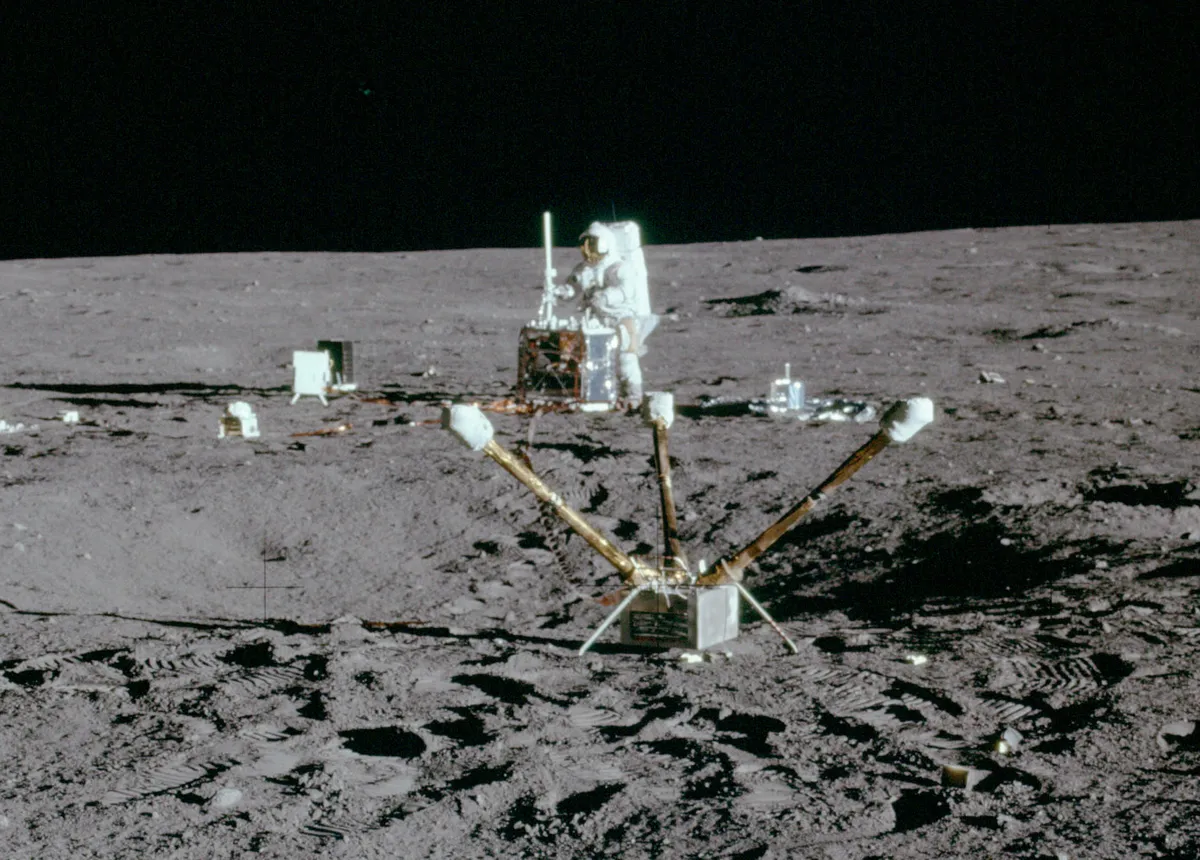

The pair did manage to successfully set up the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP), a set of experiments that would keep running after they’d left the Moon behind.

After four hours on the surface, the duo returned to the module to sleep.

They had to do so in their space suits, as removing them risked letting the highly abrasive (not to mention chafing) lunar dust into the suits’ delicate joints.

Once recovered, they ventured out on a second lengthy excursion, taking numerous samples before walking over to where Surveyor 3 was perched on the edge of a crater.

This was the first, and so far only, time humanity has revisited a robotic probe after it’s landed.

Wanting to test the long-term effects of solar radiation and exposure to space on the probe, the astronauts unbolted several pieces of the spacecraft to take home for analysis.

The mission now done, the pair returned to the lunar module before launching off the surface to reunite with Gordon.

4 days later they were preparing to re-enter Earth’s atmosphere. While the crew themselves were calm, back in Mission Control things were a lot more tense.

There was a chance the lightning strikes during take-off had prematurely released the landing parachutes.

If so, they wouldn’t work properly, and the crew would plunge to Earth and certain death.

Knowing there was no way to fix such a fault, NASA had kept the information from the crew.

The ground crew could only watch and hope as Yankee Clipper fell towards Earth. Fortunately, nine minutes into its descent, right on cue, the parachutes deployed.

The capsule splashed down in the choppy Pacific Ocean, and the crew were recovered by USS Hornet shortly afterwards.

The mission had been a success, but it had been one tinged with failure.

Several magazines of photographic film had been lost or damaged, not to mention the accidental destruction of the colour camera.

Both losses were a blow to scientists hoping to study the images, but the latter held far more dangerous consequences for the future of Apollo.

TV networks had cleared their schedules and sold advertising slots to show the first live colour footage of a moonwalk, only to end up with nothing to broadcast.

With public interest beginning to wane, there was already talk of cancelling the later Apollo missions, and the voices of the project’s many opponents were growing louder.

To get things back on track, NASA could only hope things would go better during their next mission – Apollo 13.

Apollo 12: the mission brief

Launch date: 14 November 1969

Launch location: Launch Complex 39 A

Landing location: Ocean of Storms

Time on surface: 1 day, 7 hours, 31 minutes

Duration: 10 days, 4 hours, 36 minutes

Return date: 24 November 1969

Main goals: scientific exploration of the Moon; colour TV broadcast from surface

Firsts: multi-EVA surface mission; return to a space probe; human to fall over on the Moon

Scientific instruments: Seismometer; magnetometer; solar-wind detector; suprathermal ion detector; cold cathode gauge (measures tenuous lunar atmosphere)

Meet the astronauts

Commander: Charles ‘Pete’ Conrad Jr

Conrad started his aviation career in the US Navy before becoming one of the Mercury Seven astronauts, despite rebelling against invasive medical checks by delivering his stool sample in a box tied with a bow. Before Apollo he flew two Gemini missions, and later took part in Skylab 2. He died on 8 July 1999, following a motorcycle accident.

Command module pilot: Richard F Gordon Jr

Gordon joined the Navy in 1953, becoming a test pilot before joining NASA in 1963. He and Conrad had been friends for many years, having met as roommates on USS Ranger and serving together on Gemini 11. After Apollo he helped to design the Space Shuttle before retiring in 1972. He passed away on 6 November 2017.

Lunar module pilot: Alan L Bean

Bean joined NASA alongside Gordon in the 1963 astronaut class. Apollo 12 was his first space flight, after which he took part in the Skylab 3 mission. He left NASA in 1981 to become a painter, creating scenes from his moonwalk and often working small pieces of his moondust-stained mission patches into the paint. He died on 26 May 2018.

Apollo 12 mission timeline

14 Nov 16:22 Apollo 12 launches and is struck by lightning after 36 seconds and again 16 seconds later

14 Nov 19:15

The capsule leaves Earth orbit

14 Nov 19:40

The command module Yankee Clipper separates from the launch vehicle then extracts the lunar module, Intrepid

18 Nov 03:47

Burn to enter lunar orbit begins

19 Nov 04:16

Lunar module disconnects from command module and descends towards surface

19 Nov 06:54

Intrepid touches down on the lunar surface

19 Nov 11:32

First moonwalk, lasting 3 hours 56 minutes

20 Nov 03:54

Second moonwalk, lasting 3 hours 49 minutes

20 Nov 14:25

Lunar module takes off from the Moon’s surface

24 Nov 20:53

Despite fears of lightning damage, the parachutes open as expected after re-entry

24 Nov 20:58

Crew splashdown 800km east of American Samoa

All times are GMT.