When Apollo 14 launched on 31 January 1971, it carried the weight of the entire Apollo programme. The Apollo 13 rescue had recaptured the public’s dwindling interest, but for all the wrong reasons. Policymakers already questioning Apollo’s high cost, having cancelled Apollo 18 and 19 in September 1970, now wondered at its safety.

If the remaining missions were to fly, then Apollo 14 had to be a success.It was a heavy responsibility, and one that rested on the most inexperienced crew of the whole Apollo programme.

More spaceflight history:

- Interview with Space Shuttle Flight Director Paul Dye

- How Mission Control saved Apollo 13

- Alexei Leonov: the first person to spacewalk

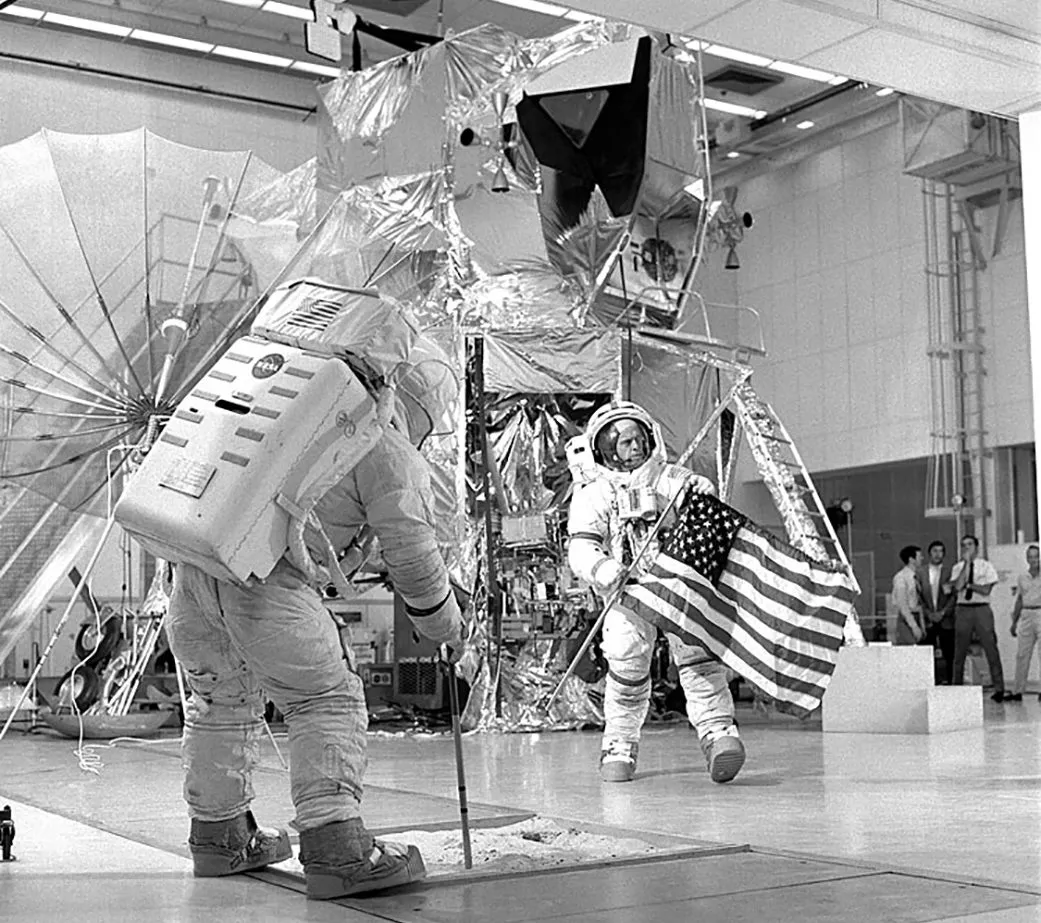

The Commander, Alan Shepard, was one of NASA’s most famous astronauts, having been the first American to reach space back in 1961.However, he’d spent the best part of the intervening decade grounded due to an ear problem that caused vertigo.

Joining him were two rookie astronauts – Command Module Pilot Stuart Roosa and Lunar Module Pilot Edgar Mitchell – neither of whom had flown in space.

Despite having a sum total of 15-minutes spaceflight experience, the mission had the most intensive scientific programme yet.

Who were the Apollo 14 astronauts?

Commander Alan Shepard

At 47, former navy pilot Alan Shepard was the oldest Apollo astronaut. He was the first American in space during his Freedom 7 mission on 5 May 1961. He served as Chief of the Astronaut Office from 1963-1969, before joining the Apollo programme. He left NASA in 1974 to pursue philanthropic ventures. He died on 21 July 1998.

Lunar Module Pilot: Edgar Mitchell

Mitchell was originally a navy pilot, joining NASA in 1966. After leaving in 1972, he continued to pursue his interest in the paranormal, including setting up the Institute for Noetic Sciences to investigate the metaphysical power of the human mind, and made several statements about UFOs before his death on 4 February 2016.

Command Module Pilot: Stuart Roosa

Roosa began his career as a ‘smokejumper’ – rapid response firefighters who parachute into wildfires – before joining the Air Force. He was selected as an astronaut in 1966, but Apollo 14 was his only spaceflight. He later worked on the Space Shuttle programme until retiring from NASA in 1976. He died on 12 December 1994.

What was the Apollo 14 landing site?

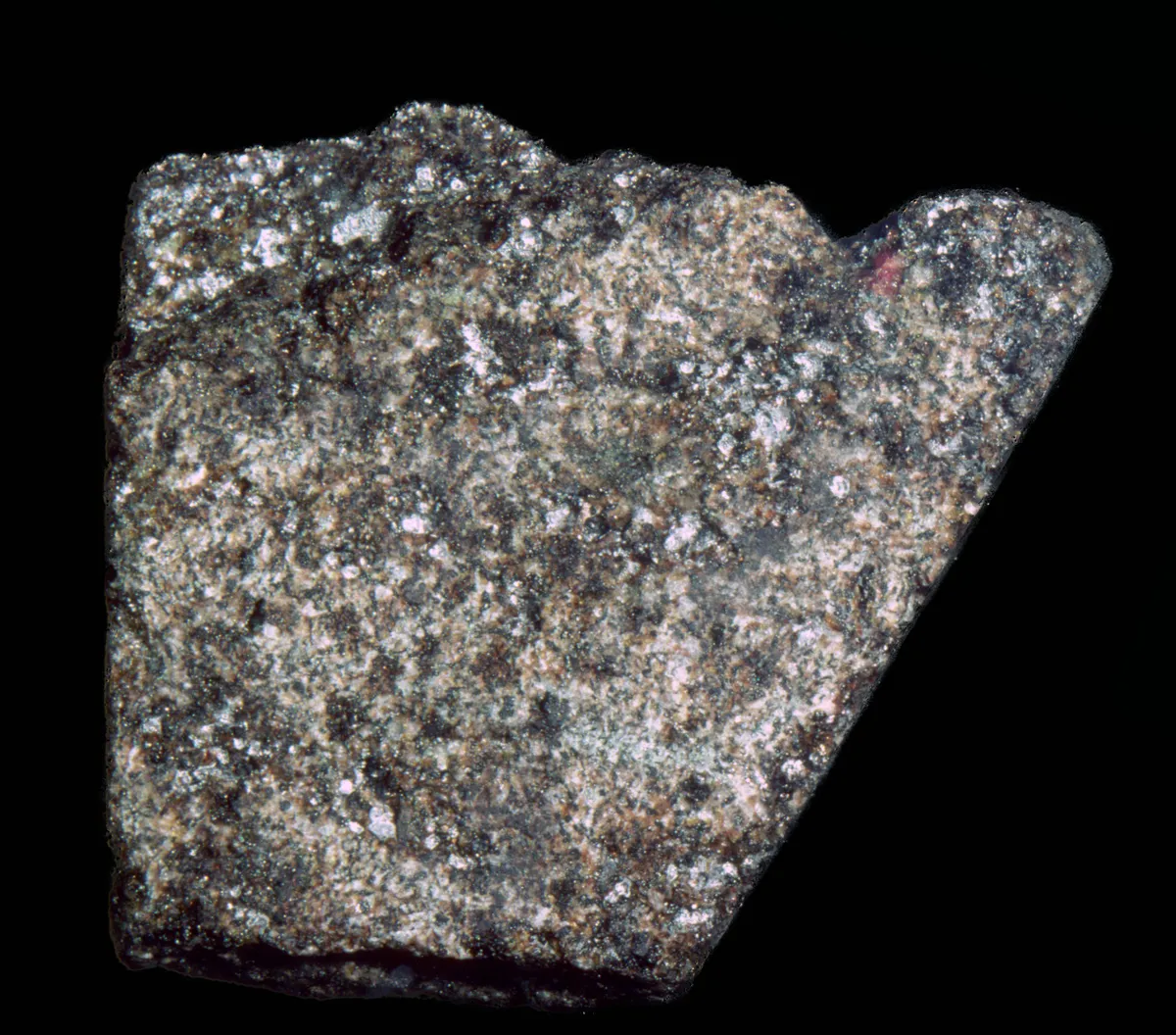

Apollo 13 had been heading towards an important landing site – Fra Mauro, a formation created by the ejecta of the collision which created Mare Imbrium.

This impact would have kicked up rocks from much deeper beneath the surface, which could potentially allow geologists to date the formation of the Moon.

With the risk that the Apollo programme could be cancelled at any moment, Apollo 14 was re-planned to visit this scientifically vital area.

The importance of the site, however, was somewhat lost on the two moonwalkers, Shepard and Mitchell. Neither were geologists and though they had had a crash course in identifying rocks, Shepard never developed an interest in the science.

Whether his celebrity ego or the pressure of commanding the mission after a decade on the ground was to blame, his lack of enthusiasm rubbed off on Mitchell.

Launching Apollo 14

When launch day came around, NASA was hoping for an easy start to the mission, only for bad weather to cause a delay.

If the skies didn’t clear within the four-hour launch window, the mission would be scrubbed until March, leaving the rocket open to the elements on the launch pad for a month.

Fortunately, after 40 minutes the weather improved, and the crew of Apollo 14 began their journey to the Moon.

It only took a few hours for things to go wrong again. When Roosa attempted to extract the Lunar Module, Antares, and dock it with the Command Module, Kitty Hawk, the two refused to latch together.

If he couldn’t get them connected, the lander was useless and there’d be no landing. After five failed attempts, Roosa took a last-ditch brute force approach, finally making the connection.

Thankfully, this course manoeuvre didn’t damage Antares and the Apollo 14 lander touched down successfully on the lunar surface on 5 February 1971.

The crew immediately prepared for their first extra vehicular activity (EVA), only to discover a fault in the communications system, requiring another delay. Had they come this far only to fail at the last moment?

Fortunately, the problem was quickly fixed and just five and a half hours after landing on the Moon, Shepard and Mitchell were ready to head out.

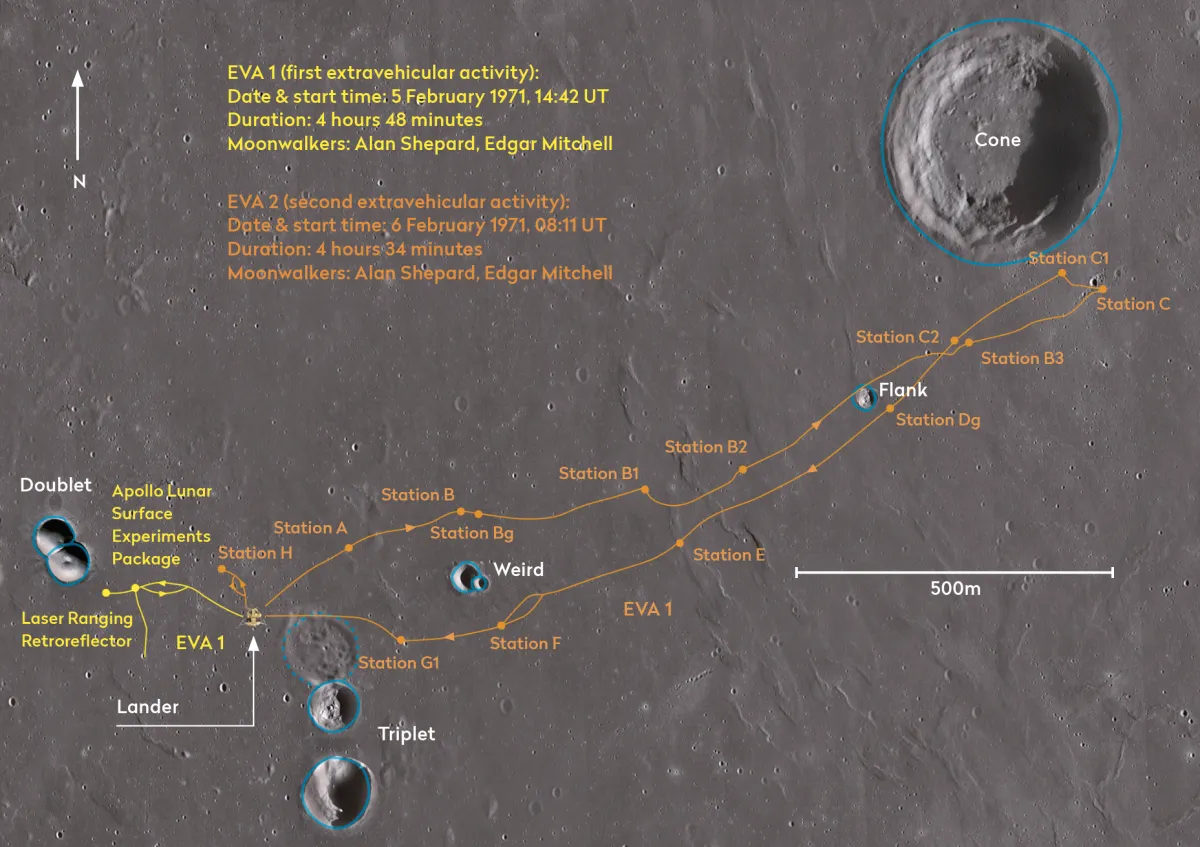

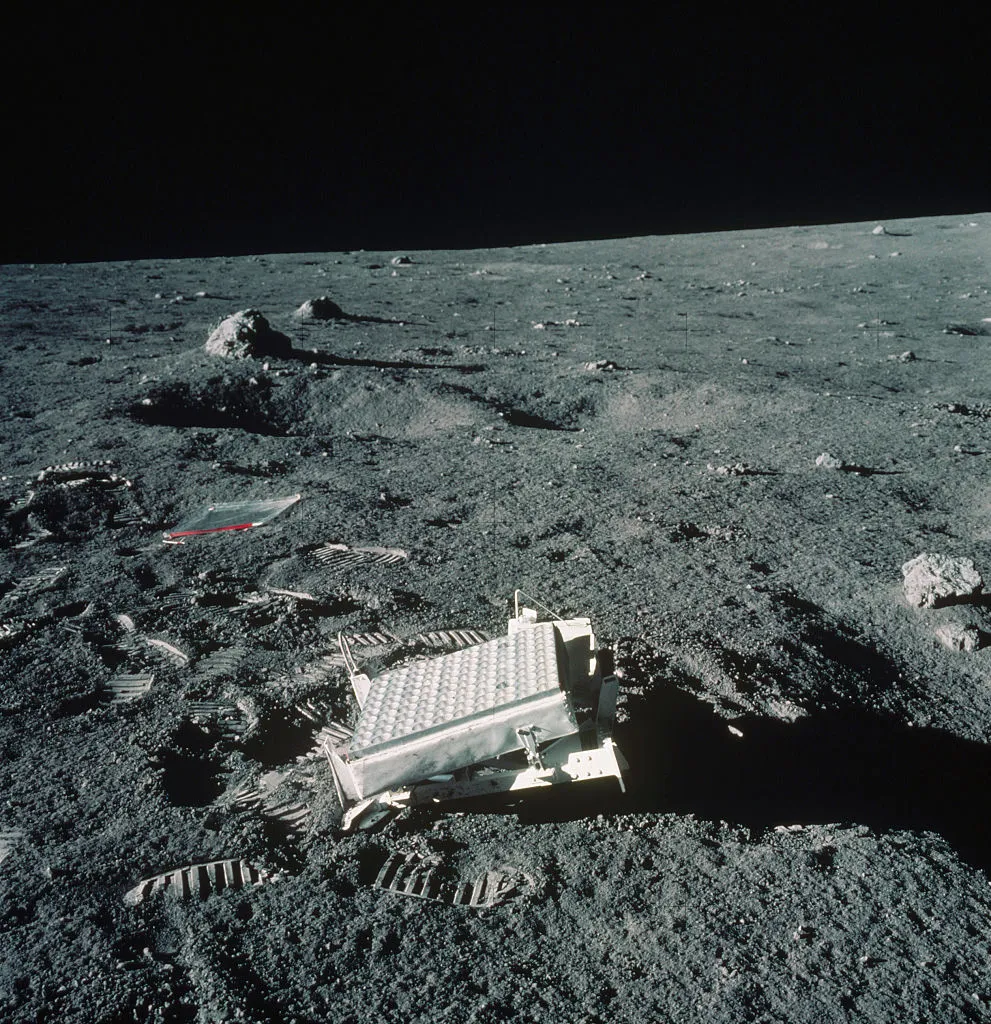

For their initial sojourn, the astronauts didn’t stray far from Antares, instead using the time to offload their equipment and set up experiments around the lander.

While many of these were the same suites of seismometers and detectors from previous missions, one novel experiment involved detonating dozens of ‘thumper’ charges, the vibrations of which were picked up by instruments left on previous landings.

What were Apollo 14's scientific experiments?

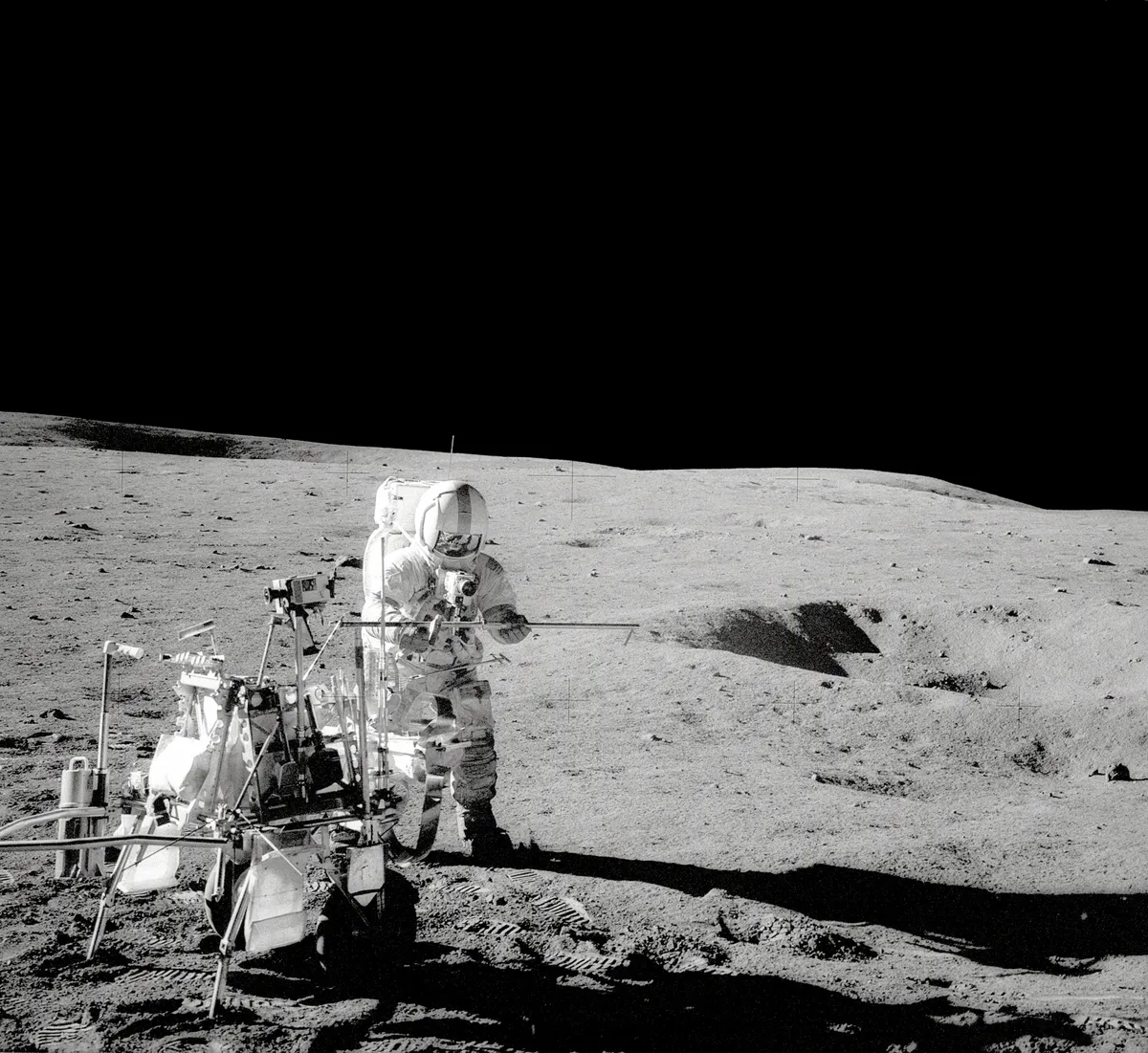

The second EVA the next day, however, was much more demanding. The moonwalkers had to live up to the ‘walk’ part of their name and trek towards crater Cone around 1km away.

It was the longest journey of the programme so far and to help cart their equipment around, the crew used a wagon officially named the Modular Equipment Transporter, but known to the astronauts as the ‘rickshaw’.

The pair soon found navigating the lunar surface was far harder than either had anticipated. With no atmosphere to diffuse the light, it was difficult to judge distances, while landmarks that were obvious on maps became unrecognisable on the surface.

“You can sure be deceived by slopes here,” said Mitchell while on the surface. “The Sun angle is very deceiving.”

After two hours, the pair thought they were about to reach the crest of the crater’s rim, only to see the field of boulders stretching out before them. The long walk pulling the heavy cart was rapidly exhausting the astronauts and Mission Control was getting worried about their rapid heart rates.

The pair were given another 30 minutes to find crater Cone’s rim before they were told to stop, take their samples and come back. It would later turn out that the astronauts had stopped just 20m short of the crater’s edge.

Meanwhile, in orbit, Roosa was conducting his own scientific study – the first time a Command Module pilot had been called on to do so.

He was meant to image the lunar surface with a special Hycon Lunar Topographic Camera, but the shutter kept sticking, ruining half of the images.

Fortunately, he managed to snap a few photographs with the Hasselblad cameras carried by every Apollo crew, including some shots of the future landing site of Apollo 16.

Back on the surface, the moonwalkers returned to the lander, but just before climbing onboard, Shepard pulled out a 6-iron golf club head he’d smuggled on board.

He attached it to the handle of his lunar excavation tool and proceeded to take a couple of drives.“There it goes,” said Shepard. “Miles and miles and miles.”

This didn’t go over at all well with the scientific community. While lining up his swing, Shepard had put down a canister of photographs documenting several of the rock samples they’d collected, and he forgot to pick it up afterwards.

Not only had the geology teams missed out on getting the samples from the rim of crater Cone, they now lacked the documentation that would really let them exploit the scientific usefulness of the ones they did have.

The feelings of ill-will only grew when Mitchell, upon his return to Earth, publicly announced that he’d conducted an unofficial pseudoscience experiment, attempting to psychically transmit messages back to Earth.

While headlines and history books remembered Apollo 14 for Shepard’s golf swing, for many at NASA it was a squandered opportunity.

The moonwalkers were meant to bring back the most important moonrocks of the entire programme, reminding people of the importance of Apollo. Instead, they were seen as making a mockery of everything the agency was trying to achieve.

Timeline of Apollo 14 events

*All times are UT

31 January 20:15Countdown paused with eight minutes left on the clock

31 January 21:03Apollo 14 launches

31 January 21:03Engine burn sends the spacecraft on a trajectory towards the Moon

1 February 00:16First attempt at docking the Lunar Module (LM) and Command Module (CM)

1 February 01:59Docking finally successful

3 February 08:53LM pressurised; the Commander and Lunar Module Pilot transfer across

5 February 09:18The LM lands on the Moon’s surface

5 February 14:42First EVA begins

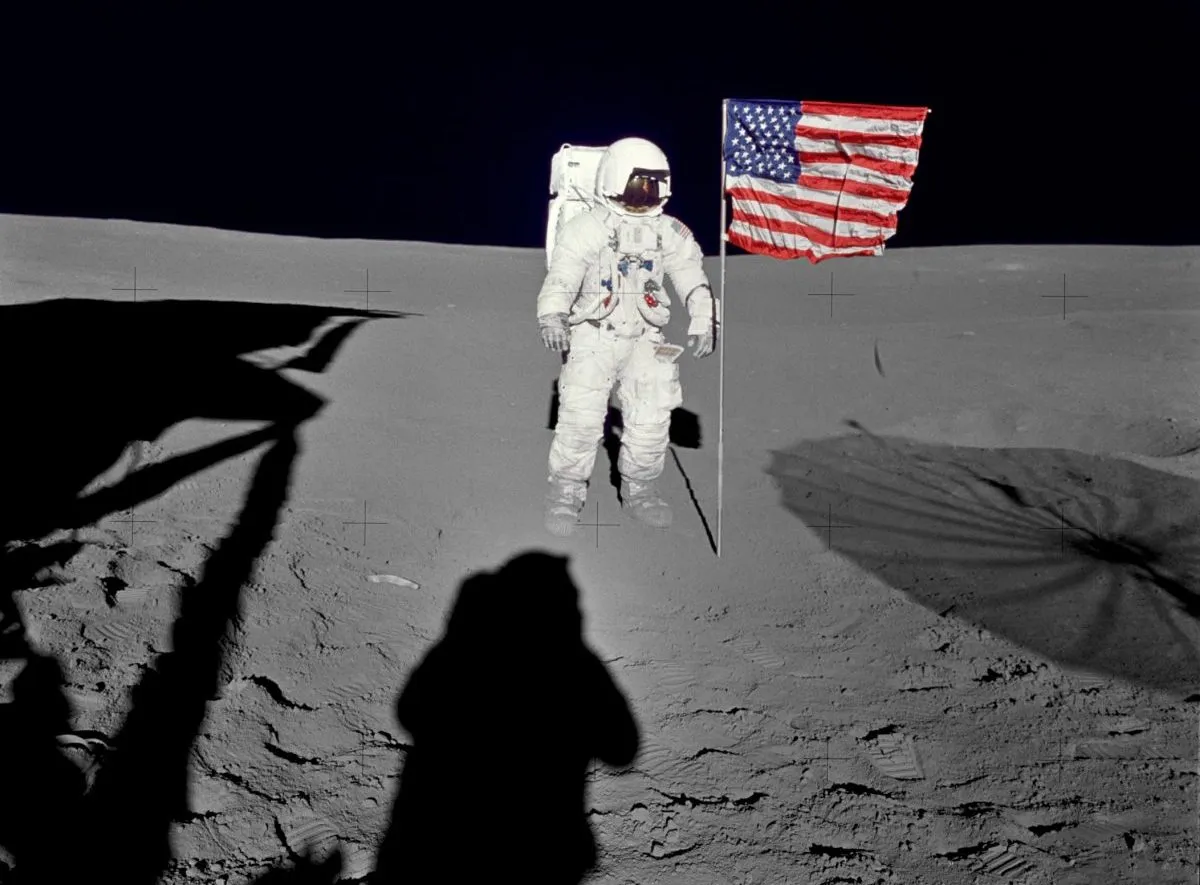

5 February 15:44US flag deployed on the surface

6 February 08:11Second EVA begins. Shepard and Mitchell begin hike to crater Cone

6 February 10:43Moonwalkers reach Station C1, the closest point to crater Cone

6 February 18:48The LM launches from the Moon

6 February 20:35The LM redocks with the CM

9 February 21:05The CM splashes down on Earth

Dr Ezzy Pearson is BBC Sky at Night Magazine’s news editor. She gained her PhD in extragalactic astronomy at Cardiff University. This article originally appeared in the January 2021 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.