When Buzz Aldrin talks to you, it is most often about spaceflight. And the discussion will not be primarily the reminisces of an aging moonwalker: no, this discussion will be about the future. The future of spaceflight, the future of America’s role in it, the future of internationalism, and the future of humanity.

You see, Buzz is a visionary, and vision is something that must be shared. Buzz Aldrin has not slowed much.He still stands ramrod-straight, speaks with energy and passion, and continues to generate new ideas constantly.

More about Apollo 11

Buzz founded the Human SpaceFlight Institute to seek more collaborative approaches to leaving our planet, and is seeking to create a global alliance of spacefaring nations to facilitate international cooperation in space exploration and development.

“I want to put together an advisory group with the National Space Council - a world alliance for space exploration," he tells me.

"NASA, the European Space Agency, Japan and China. Let NASA put it together, then the partners talk to each other about opportunities.

"NASA can then bring in ULA, SpaceX and Blue Origin. Of course, this creates problems with vested interests, but if you supply the foreign markets and foreign contributions, a space exploration alliance makes more sense.”

If this sounds lofty, it is. If it sounds ambitious, doubly so. But that’s how Buzz rolls.

He’s not a man of small ideas, and at an age where many people are more worried about a new recliner than new spaceflight alliances, he is a remarkable and energetic exception, always thinking, always planning.

He’s aware that the time to complete his legacy is now, and never stops working on it.

Says Roger Launius, a former curator of space history curator at National Air and Space Museum: “He doesn’t stop. He could if he wanted.”

Aldrin's early life

Buzz - formally Edwin Eugene Aldrin Junior - was born on January 20, 1930, into a family wrapped in military tradition.

His father had been an aviator in World War One and was assistant commandant at the U.S. Army’s test pilot school for 3 years after that conflict, and was an executive for Standard Oil by the time Buzz was born.

Edwin Sr. had planned for his son to attend the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, and used political connections to pull in an appointment as Buzz neared high school graduation.

But Buzz had other ideas the straight-A American football star of Montclair High School in Montclair, New Jersey wanted to go to West Point, where the Army trained its officers.

His father eventually relented, and in 1947, off Buzz went to New York.

Credit: NASA

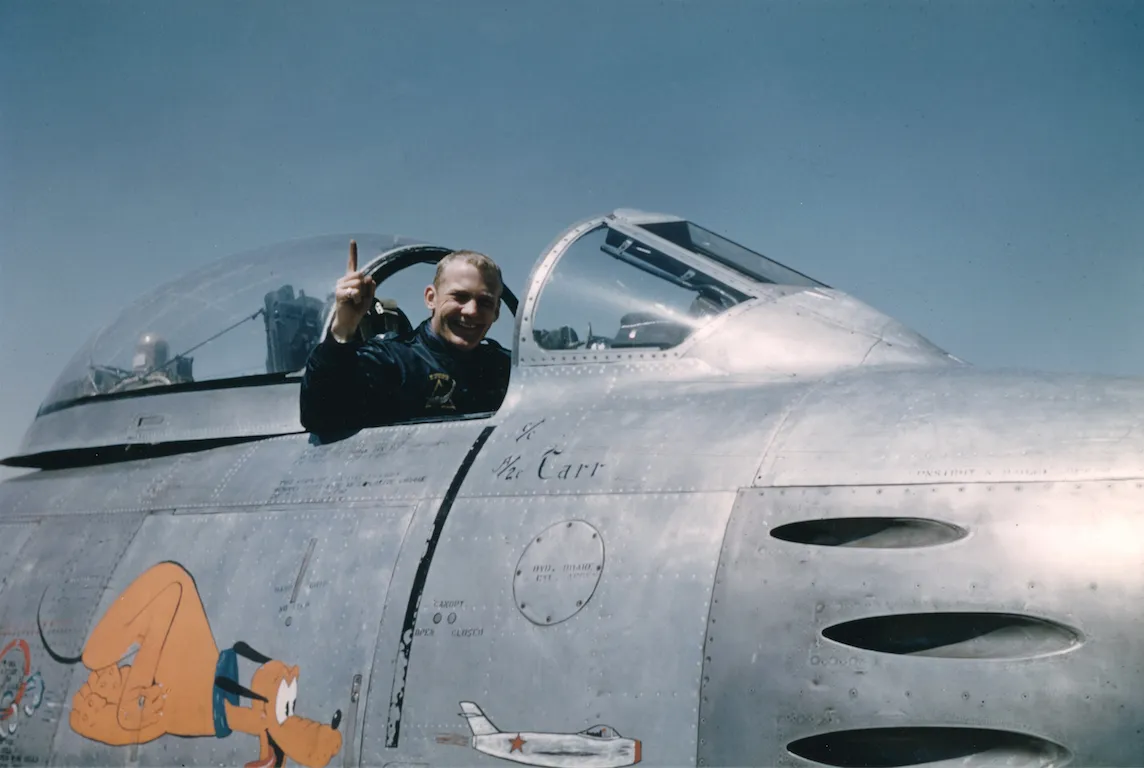

West Point led to a commission in the U.S. Air Force, and by 1952 he was flying fighter jets in Korea.

After shooting down two Migs and earning number of flight medals, he was back in the United States for more training.

After a 3-year assignment flying jets in Europe in support of NATO’s mission there, Buzz enrolled at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to pursue higher education in engineering, eventually leading to a doctorate in astronautics with an emphasis in manned orbital rendezvous. This was not strictly an academic decision.

“The country was swept up in the space program, and I wanted to be a part of it,” Aldrin recalls, “But NASA retained its requirement that astronauts have a diploma from a military test pilot school—not one of my credentials.

"Since I knew that the moonlanding program Kennedy had described would need astronauts with skills other than the ones they drummed into you at test pilot school, I opted for another eighteen months of intensive work on a doctorate in astronautics, specialising in manned orbital rendezvous.”

In his dedication to the dissertation, he wrote, "In the hopes that this work may in some way contribute to their exploration of space, this is dedicated to the crew members of this country's present and future manned space programs. If only I could join them in their exciting endeavours!"

How prescient this would prove to be.

It took two applications to become a NASA astronaut, but by 1963 he was accepted and was immediately assigned to working on orbital dynamics and rendezvous for the upcoming Gemini program.

Gemini started flying in 1965 and continued through 1966, with Buzz’s Gemini 12 flight the last of the program.

As with all the Gemini flights, there was a long list of objectives to be fulfilled, but perhaps the most critical at that point was that of extra vehicular activity or EVA, also known as spacewalking.

Performing tasks during EVA was deemed a critical step for the Apollo program, and had not yet been mastered despite many attempts on previous Gemini flights.

These attempts—which had not received the preparation they should have—resulted in fatigued, disoriented, exhausted astronauts who had been unable to accomplish all their EVA goals.

Aldrin’s mission was the last chance to get it right.

Buzz was determined to hit his marks. Alone among his colleagues, and sometimes at the butt-end of their ridicule, he spent countless hours over months training for his EVA.

The others had trained, yes, but nobody to nearly this extent or with Aldrin’s ferocity.

He went up in the zero-g simulator aircraft again and again and used other NASA Gemini trainers, but was not convinced that this was enough to assure success.

NASA had started experimenting with underwater training. although it was just a nascent effort at this point.

The space agency did not even have a water tank for such activities, and so it leased time in a pool at a nearby high school (having to make scheduling allowances for water polo practice).

Aldrin, already an avid scuba diver, seized on this - what would later become known as neutral-buoyancy training - and could be found day after day, sealed in a Gemini pressure suit, in the deep end of the pool clambering over the Gemini simulator there.

Then on November 11, 1966, it was time to strut his stuff.

Gemini 12 and spacewalk

Gemini 12 launched shortly after the Agena target vehicle with which it would rendezvous and dock, and but there was trouble just a few hours later.

Soon after the Gemini’s radar acquired the still-invisible Agena stage, now 225 nautical miles (473 km) away, the onboard radar failed.

Undeterred, Aldrin - they didn’t call him 'Doctor Rendezvous' for nothing - pulled out some navigational charts, a sextant and a slide rule, and manually calculated where the Agena should be.

“The fallback for this situation was for the crew to consult intricate rendezvous charts - which I had helped develop - to interpret the data using the ‘Mark One Cranium Computer,’ the human brain," Aldrin would later say.

Commander Jim Lovell completed the docking, using less fuel than previous flights, and they laughingly checked-off the manual rendezvous exercise, which had been scheduled for later in the flight.

A day later, Aldrin’s second EVA would be a true test of his mettle.

Leaving Gemini capsule, he carefully - and in comparison to his predecessors, effortlessly - made his way first to the Agena to set up an experiment, then moved back to the rear of the Gemini capsule to an experimental station.

The astronauts called it "the busybox". Once there Aldrin performed the tasks that had so vexed his predecessors, torqueing bolts and adjusting fixtures. It went like clockwork.

As he later said, “Project Gemini had finally triumphed. All of its objectives had now been met. We were ready to move on to Project Apollo and the conquest of the Moon.”

Apollo 11

Crew selection for Apollo 11 came in 1968 during the flight of Apollo 8.

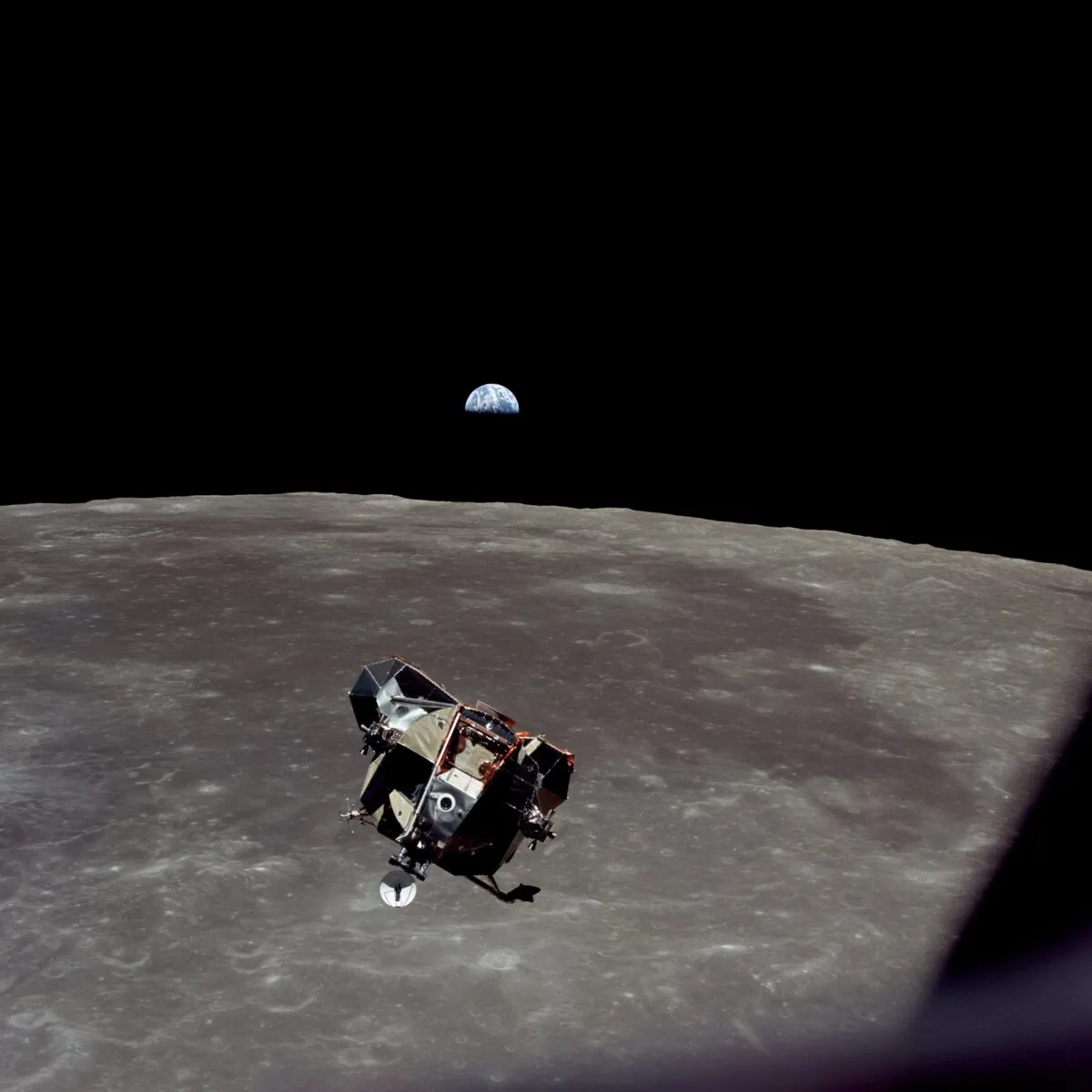

Neil Armstrong would be the commander, Buzz the Lunar Module Pilot, and Mike Collins the Command Module Pilot.

But as they dove deep into training for this mission, one question had not yet been resolved: who would exit the Lunar Module and set foot on the Moon first?

Buzz thought it made sense for this to fall to the Lunar Module Pilot—in previous EVAs it had always been the second in command who left the spacecraft.

“In the history of NASA EVAs, the guy who got out was always the junior person... But I understood that ultimately public image was important in this case, and we needed a decision - this concern could delay training.”

Armstrong had his own ideas and would not rule out the option of being first out. Aldrin took his concerns to senior management and got his decision: Armstrong would be first out, and that was that.

Training continued for 6 more months, and then it was time to go.

On 16 July 1969, everything that could be done to prepare for the first landing attempt had been done, and at 9:32 am Eastern Time, they were off. Apollo 11 bolted into a perfect blue Florida sky.

Three days and a harrowing landing later, Aldrin and Armstrong were on the lunar surface, and it was time to get out and explore the Moon.

They suited up and opened a valve to depressurise the LM’s cabin, but when they tried to open the hatch, it would not open.

After looking at the pressure gauge and trying again, it was still a no-go. The hatch would not budge.

There was still just a bit too much air pressure inside the LM. Aldrin was nonplussed.

“We didn’t fly 240,000 miles to not explore the Moon,” he told me. “I reached down and grabbed the corner of the hatch and flexed it back—there was a hiss of escaping oxygen, and it swung open. You do want to be a little careful about not bending that door, however” he added with a chuckle.

Armstrong got out first, inadvertently breaking a small plastic switch as Aldrin manoeuvred him out of the LM’s hatch.

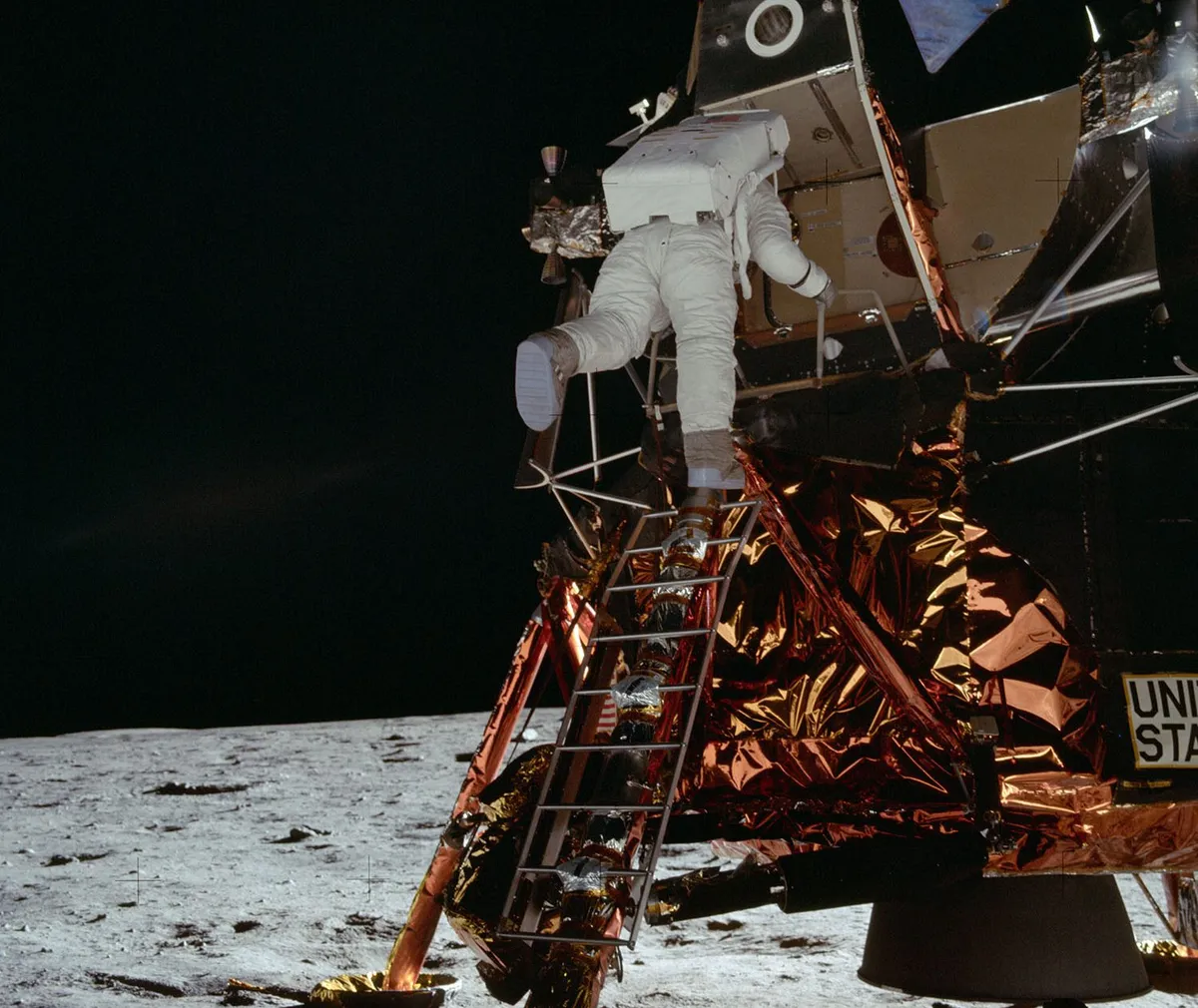

Aldrin followed him down the ladder about 20 minutes later. While Armstrong went down in the history books for his famous first words on the Moon, Aldrin would prove to be among the most poetic of all the Apollo astronauts.

As he turned away from the ladder to step onto the surface, he said, “Beautiful view.” Armstrong retorted, “Isn’t that something? Magnificent sight out here.”

After a pause, Aldrin replied, almost dreamily, “Magnificent desolation.” It was a perfect—and lyrical—description of the lunar surface.

For the next two and a half hours the pair gathered rocks, set up experiments and took photos and measurements as laid out by a very aggressive timetable.

Then Aldrin went back up the ladder, followed by Armstrong. They buttoned up the LM, cleaned up, and it was then that they noticed the small plastic tab on the floor of the lunar module.

The switch that Armstrong had broken with his backpack as they left the spacecraft was the ascent engine arming breaker - the very switch they would throw to return to lunar orbit.

While they rested, Mission Control developed a workaround to bypass the switch, but as the astronauts prepared for lunar liftoff about ten hours later, the ever-pragmatic Aldrin looked at the breaker - now just a plastic hole in a panel - pulled a felt-tipped pen out of his pocket, and jammed it inside.

The switch closed and they were soon ready to go. Problem solved for less than the cost of a beer.

Under 3 days later they were bobbing in the Pacific Ocean, awaiting pickup by the Navy.

But their ordeal was not over. They would have to don biocontainment suits before getting out of the capsule and would then spend the next 3 weeks in quarantine to assure than they had not brought any dangerous germs back from the Moon.

“It was a bit of a blessing,” Aldrin would later say. “We had time to decompress.”

At one point during their lockdown, Armstrong and Aldrin were watching recorded footage of the moonwalk. Aldrin smirked, and turned to Armstrong who was just staring at the screen.

He recalls saying, “Neil, you know what? We missed the whole thing!”

In a sense, he was right—they had been so busy completing their lunar chores there had been little time for it to soak in.

After a whirlwind tour of U.S. and 25 world capitals, the crew went their separate ways.

After Apollo 11

Armstrong secured a teaching appointment in aeronautical engineering at the University of Cincinnati, while Mike Collins eventually became the head of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum.

But Aldrin’s post-NASA life took a very different trajectory. As they recovered from the world tour, Collins noted that Aldrin had seemed to be quite withdrawn - almost depressed - and he was right.

Over the next number of years, Buzz struggled with depression and eventually alcoholism.A divorce resulted; two more marriages came and went.

But neither the relationships, three wonderful children, nor the various assignments he received seemed to help. Buzz was struggling to find new relevance in his life after the mission of Apollo 11.

In his books about his career and the missions of Apollo and Gemini, Buzz spoke openly about his struggles with depression and alcohol: an incredibly bold step during an era in which combat pilots and astronauts did not discuss such things with each other, much less announce them to the public.

But Aldrin felt it was important for the world to know the pressures people such as himself worked under, and is was likely a cathartic process for him as well.

By the 80s, things were improving. Aldrin had written a number of books, was energetically pursuing his agenda of advancing the human presence in space and had become somewhat of a media darling.

There were appearances on numerous TV shows, autograph signings, and a demanding schedule of talks and other media appearances.

And he has, since the mid-1980s, served tirelessly on the Board of Governors of National Space Society, a large pro-space organisation. But always, his core ambition has been to push the development of human spaceflight beyond Earth orbit.

“About 1985 I began looking at how we might go to the Moon and Mars with free return trajectories—to swing around and return from these places, and this led to the cyclers,” he tells me.

His Aldrin Mars Cycler - now joined by a design for lunar trips - employs a large spacecraft that would be placed into a continuous, looping trajectory between the Earth and either the Moon or Mars, with smaller shuttles carrying crew to and from the cycler.

In this way, the cycler acts as a continuous transport - with comfort and radiation protection for its crews - with the shuttles or 'taxis' moving from the cycler to Earth, the Moon, Mars or its moons.

It’s a brilliant plan, and one that he can describe at the drop of a hat.

In his ninth decade, Aldrin is still a vibrant force for expanding the human presence in space.

Alone among the astronauts of Apollo, he has continuously and vigorously campaigned for NASA to continue its journey beyond Earth orbit.

He is also a prominent voice for internationalism in space, pushing for greater collaboration with a number of nations, most notably with China.

The relationship between the United States and China is often challenging, but he sees great potential there, and feels that our best chances for success in space involve unity and shared successes.

Aldrin has traveled the globe tirelessly to deliver this message, and recently formed the Human Spaceflight Institute to continue the push.

He serves with the National Space Council, a NASA advisory group, and is working to form a global alliance for space exploration.

“Let NASA put this together along with the Europeans, Japan, Russia and China,” he tells me,

“Then let NASA bring in SpaceX, Blue Origin” and the other commercial entities. “I'm very interested in dealing with international groups, and I’ve heard people discussing this over in China. How should we come together? It’s very crucial to not have a competition with China.

"We can work together. When we come together, we’re better at problem-solving as an international group of thinkers."

In the numerous interviews I’ve conducted with him for this article and many books, Buzz is always engaging and energetic he is a true force of nature.

It often seems as if there are five brilliant minds competing for one mouth, and the ideas and plans come fast and furious, as he continues to work towards his final legacy: humanity’s greatest adventure.

"50 years after Apollo, what can we actually do?" he recently said.

"The Space Launch System won’t [initially] even be able to get the Orion capsule into a proper lunar orbit with any real maneuvering capability," so rather than a direct landing, Orion will enter a rectilinear lunar halo orbit, where NASA has planned to place the Lunar Orbiting Gateway—which is a design forced to accommodate Orion/SLS’s limited capabilities.

"I hate the Gateway," he continues. "We don’t need a permanent orbital structure at the Moon!"

Instead, he thinks that the core of the Gateway could actually be used as a transit vehicle between the Earth and the Moon with increased efficiency if properly developed.

"If that’s not a winner, I don’t know what is," he says. But he then summed up the interactions between people like himself and NASA with a chuckle. "It’s hard to mix fighter pilots with managers."

That may be true, but after nearly a half-century of developing ideas to return humans to deep space, his ideas seem to be increasingly relevant, and can be summarised by his line of t-shirts that read 'Get Your Ass to Mars', to which he might now add, after a layover at the Moon.

"It’s time to get on with it... now."

This article originally appeared in truncated form in the January 2020 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.