Is there life beyond Earth? No one knows, but most scientists think it’s almost inevitable.

Our Universe is incredibly extended, both in space and in time, so anything that can happen – in this case, the emergence of life – is almost bound to happen more than once.

Moreover, the Universe teems with planets, and the organic building blocks of life appear to be found wherever we look.

Even though we don’t know precisely how the first living cells were formed, it’s extremely unlikely that the process occurred just once.

Enter the Habitable Worlds Observatory

Still, as yet there’s no convincing evidence of life beyond Earth.

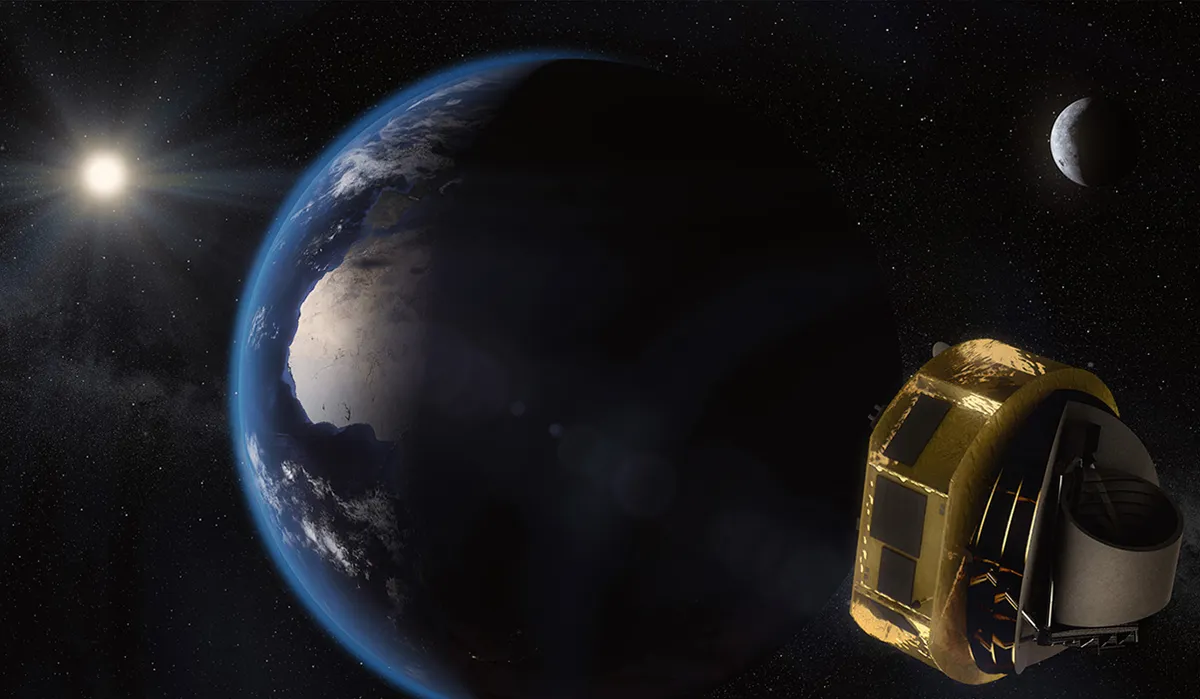

But that may change in the next two decades or so with the launch of the Habitable Worlds Observatory (HWO), a powerful future space telescope that’s currently on the drawing board.

On 1 August 2024, the project entered ‘pre-Phase A’, with the opening of the HWO Technology Maturation Project Office at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

According to NASA, the space observatory will be "the first specifically engineered to identify habitable, Earth-like planets… and examine them for evidence of life."

Exploring exoplanets for life

Since the first discovery of a planet orbiting a Sun-like star back in 1995, astronomers have uncovered more than 7,000 extrasolar planets, or ‘exoplanets’ for short.

Although small low-mass planets like Earth are much harder to detect than gas giants like Jupiter, quite a few have been found.

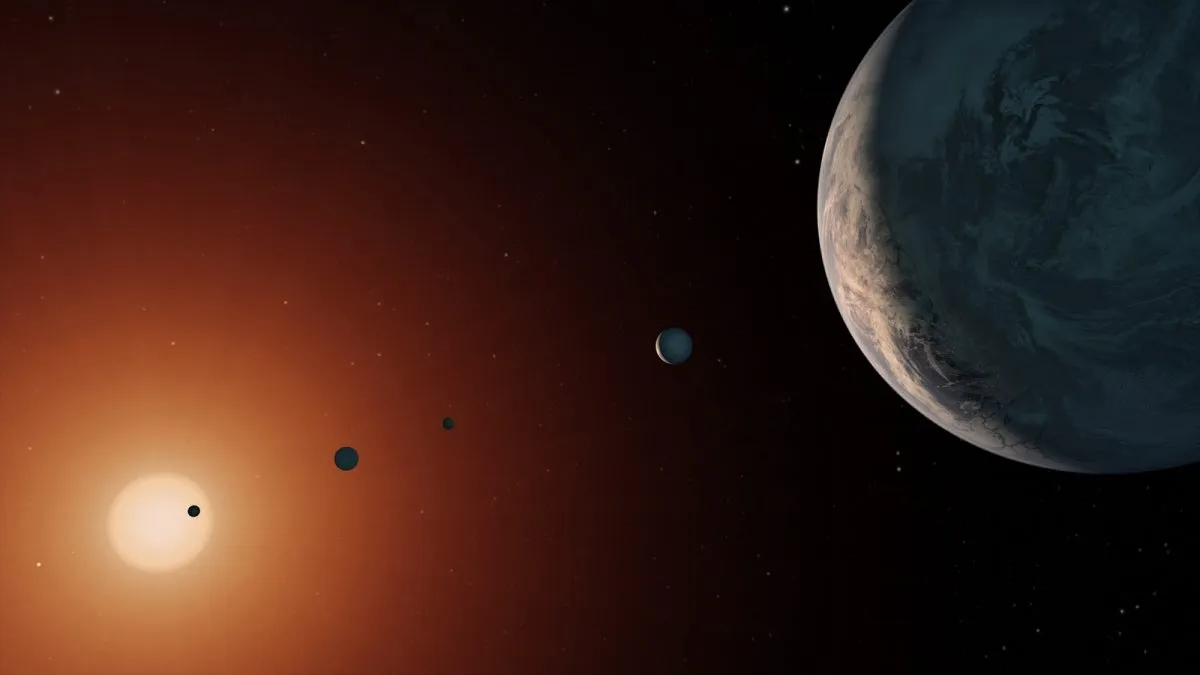

They include Proxima b, orbiting the closest star to our Sun, and the seven worlds circling the star TRAPPIST-1 (around 40 lightyears away), three of which are located in the star’s habitable zone – sometimes called the Goldilocks zone – where surface temperatures allow the existence of liquid water.

In our Milky Way Galaxy alone, there may be 20 billion similar potentially habitable planets.

So how do you check remote exoplanets for life?

The keyword here is ‘biomarkers’, chemicals in a planet’s atmosphere, like oxygen, ozone and methane, that suggest biological activity on the surface.

The relative abundance of these three molecules in the atmosphere of Earth, for example, cannot be explained by any non-biological process.

Biomarkers leave tell-tale fingerprints in the light of an exoplanet’s host star when the planet moves in front of its star: the star’s light also contains light reflected by the planet.

Sniffing out an exoplanet’s atmosphere with spectroscopy may thus reveal the existence of life, even though it wouldn’t tell us if we were dealing with microorganisms, plants or aliens.

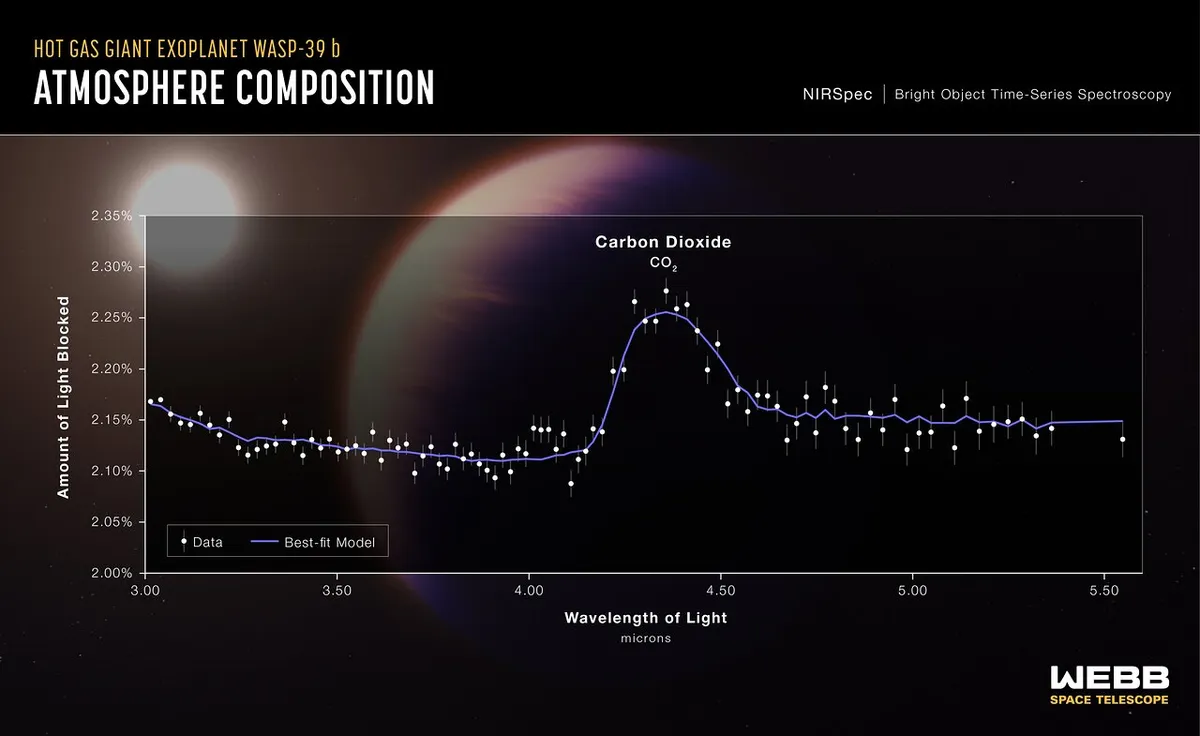

Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, and L. Hustak (STScI). Science: The JWST Transiting Exoplanet Community Early Release Science Team

Why not Webb?

Using this transit spectroscopy, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has already detected carbon dioxide, water vapour and sulphur dioxide (among other molecules) in the atmospheres of giant, gaseous exoplanets and so-called super-Earths.

However, similar measurements on potentially habitable, rocky Earth-like planets are incredibly difficult, and JWST certainly isn’t powerful enough to carry out reflectance spectroscopy on small planets.

That’s why astronomers are looking forward to the Habitable Worlds Observatory.

"Detecting life signatures would be the biggest revolution since Copernicus," says Mark Chaplin, NASA’s director of astrophysics.

Designing a new life-seeker

The history of Habitable Worlds Observatory goes back at least 15 years, when Goddard scientists presented plans for a huge 8- to 16-metre Advanced Technology Large-Aperture Space Telescope (ATLAST).

These ambitious ideas later developed into two more realistic concept studies: the Large Ultraviolet Optical Infrared Surveyor (LUVOIR), led by Goddard, and the Habitable Exoplanet Observatory (HabEx), led by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Habitable Worlds Observatory would combine elements from both, focusing not only on the search for biomarkers, but also on astrophysics.

The new facility received a strong endorsement from the latest Decadal Survey on Astronomy and Astrophysics (2020), a community-driven recommendation on US government funding.

Launch and mission

The Habitable Worlds Observatory will probably not launch before the first half of the 2040s.

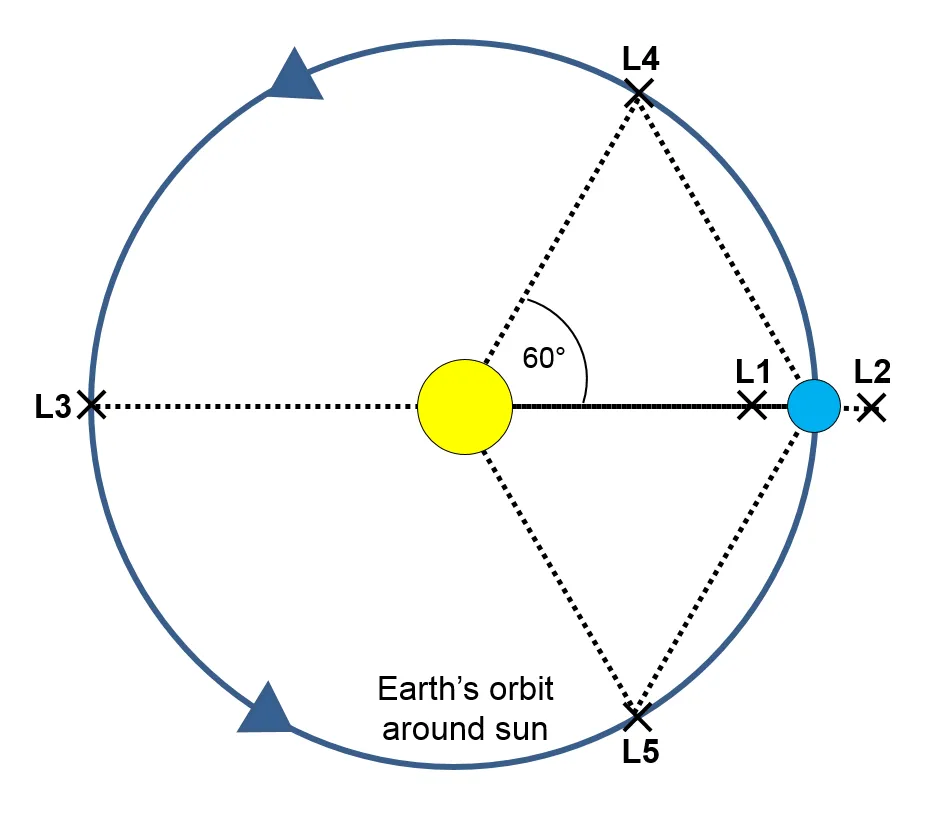

A powerful rocket like NASA’s Space Launch System, SpaceX’s Starship or Blue Origin’s New Glenn will send the telescope to Lagrange 2 (L2), a region some 1.5 million kilometres (0.9 million miles) ‘behind’ the Earth, as seen from the Sun (and also home to the James Webb Space Telescope).

The Habitable Worlds Observatory’s primary mirror will be at least six metres in diameter, so it needs to be segmented one way or another.

However, no decisions have yet been made on the detailed design of either mirror, telescope or spacecraft.

What has been decided, however, is that the Habitable Worlds Observatory will cover the same broad wavelength range as the Hubble Space Telescope, from ultraviolet through the optical into the infrared.

"It’s basically a super-Hubble," says astrophysicist Kevin France from the University of Colorado.

At least three large scientific instruments are foreseen: a high-resolution, widefield (3 x 2 arcminutes) imaging camera with dozens of filters to single out specific wavelengths; an ultraviolet multi-object spectrograph; and a coronagraph that can block starlight to reveal the faint images of closely orbiting exoplanets.

"A fourth instrument still has to be defined," says France.

For exoplanet studies, the coronagraph will be the most important instrument.

In the past, similar instruments (albeit much less sophisticated) were used to image the Sun’s corona by blocking the bright light of the Sun’s disc.

NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, slated for launch in 2027, also uses a coronagraph to study exoplanets, so by the time the Habitable Worlds Observatory is built, engineers will have ample experience with the technology.

Servicing

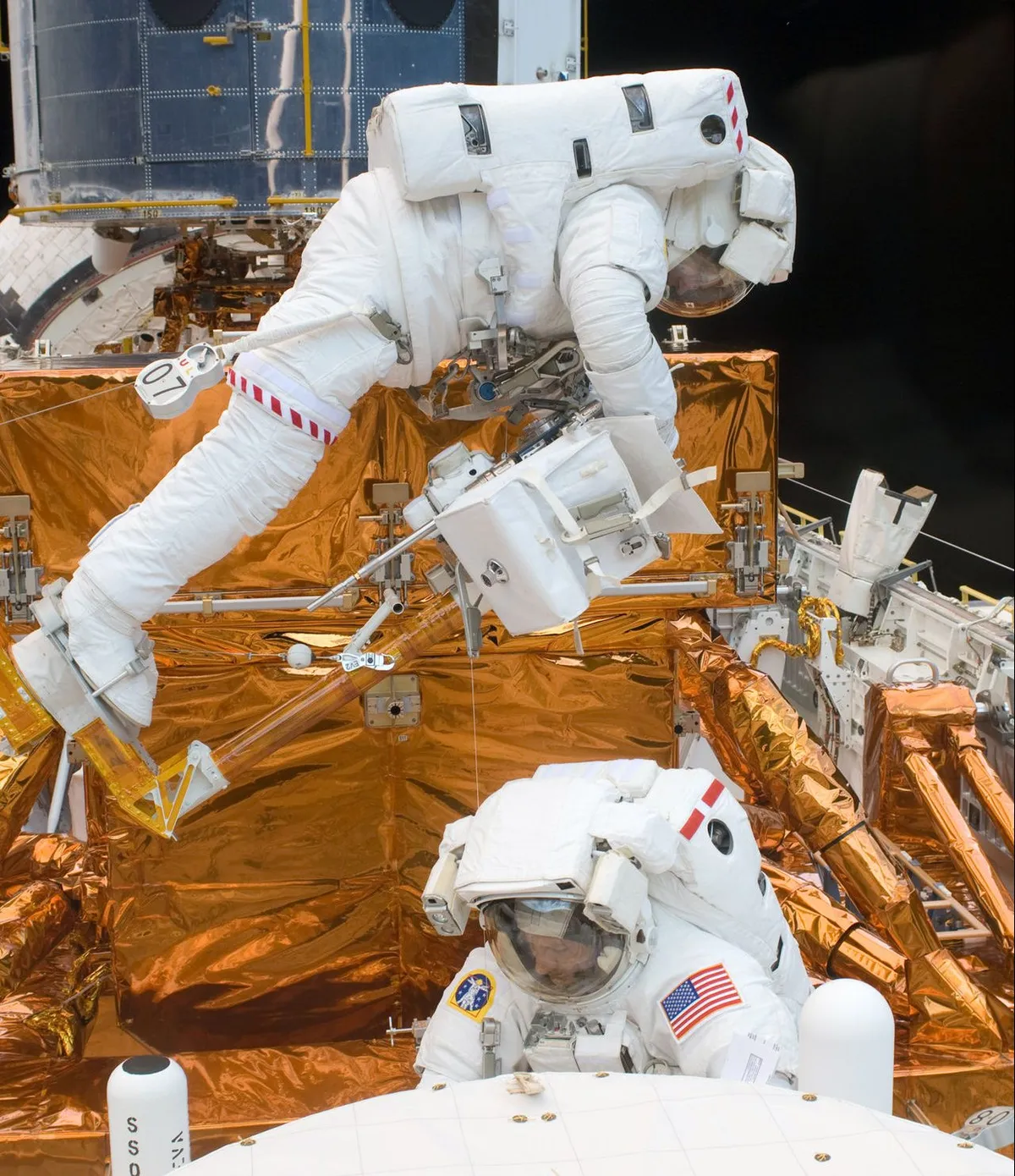

The Hubble Space Telescope, launched into low Earth orbit back in 1990, has been in operation for decades thanks to five servicing missions, the last one of which took place in 2009.

Space Shuttle astronauts have replaced malfunctioning gyroscopes and computers and outfitted Hubble with new solar panels, cameras and spectrographs.

In contrast, the James Webb Space Telescope, which doesn’t orbit Earth, cannot be serviced. Once an important component breaks down, the mission will be over.

Like JWST, the Habitable Worlds Observatory will operate from L2, a region in space almost four times more distant than the Moon.

Nevertheless, engineers plan to design it in such a way that it can be serviced – not by astronauts, but by robots.

An uncrewed mission would fly to L2, rendezvous with HWO and carry out necessary repairs or replacements.

What’s more, a key purpose of such a mission would be to install a possible second generation of science instruments, upgrading the spacecraft’s capabilities.

What Habitable Worlds Observatory could discover

However, in order to obtain a spectrum of an Earth-like planet in the habitable zone of a nearby star, the Habitable Worlds Observatory’s coronagraph must reach a contrast of 10–10.

It should be able to image a planet that is 10 billion times fainter than its host star.

Apart from imaging at least 25 nearby habitable planets and studying the composition of their atmospheres, scientists believe that HWO will also be able to detect Earth-like moons (or ring systems) of giant extrasolar planets, and observe mutual transits and eclipses of giant planets and their moons.

Casey Handmer, a former NASA JPL software system architect, even told the website payloadspace.com that he believes the current HWO approach is pretty conservative.

According to Handmer, a future space telescope could be scaled up to detect surface details on Earth-like planets like oceans and continents, albeit at a very low resolution.

"Habitable Worlds Observatory is still a long way off," says astrophysicist Paul Scowen at Goddard.

"Many new technologies still have to be developed and demonstrated."

Chaplin agrees. "First we need to mature the various technologies," he says. "Once we understand what exactly we’re building, we’ll start the detailed design, so as to reduce risks."

According to Scowen, some technologies, including micro-mirrors for multi-object spectroscopy and large-format photon detectors, will be tested in space on small-scale platforms like CubeSats and sounding rockets.

"A lot of preparatory work has been done already," he says.

The European Space Agency (ESA) is interested in becoming a partner in the project, just like it is in Hubble and the JWST.

"The goals of ESA’s long-term science plan, Voyage 2050, are very compatible with the major science themes of HWO," says Ana Gómez de Castro of the Universidad Complutense, Madrid, one of three ESA representatives in the HWO project.

According to Gómez de Castro, ESA could contribute a fourth large science instrument for the new space observatory: a high-resolution ultraviolet spectropolarimeter that would study polarised light from exoplanets, as well as from stars and galaxies.

Preparing for launch

To coordinate the early work on the Habitable Worlds Observatory, NASA established a Science, Technology, Architecture Review Team (START) and a Technical Assessment Group (TAG), both within the larger Great Observatory Maturation Program (GOMAP).

In addition, there’s a Smallsat Technology Accelerated Maturation Platform (STAMP), also funded through GOMAP, that will oversee in-space technology demonstration missions.

"We’re preparing ourselves for Phase A," says Kevin France. That’s the phase in which a proposed mission and system architecture is developed.

While Phase A could kick off in the next two years, a definitive green light for HWO is not expected before the early 2030s.

By then, two large European exoplanet missions will be operational: PLATO, expected to launch in 2026, and ARIEL (2029).

While PLATO (Planetary Transits and Oscillations of Stars) will focus on new detections, ARIEL (Atmospheric Remote-sensing Infrared Exoplanet Large-survey) will study around 1,000 exoplanets in great detail to learn about their atmospheric characteristics.

Both will help lay the groundwork for the Habitable Worlds Observatory – which may well be the most exciting and revolutionary space telescope ever.

After all, it could potentially answer humankind’s profoundest question: are we alone?

Habitable Worlds Observatory extra goals

The primary goal of the Habitable Worlds Observatory is to look for biomarkers in the atmospheres of Earth-like exoplanets that would indicate the presence of life.

But the future space telescope will do much more.

Scientists have formulated four major themes for the observatory:

- Drivers of galaxy growth

- Evolution of elements over cosmic time

- Solar System in its galactic context

- Living worlds

As astrophysicist Kevin France says: "Habitable Worlds Observatory does a little bit of everything."

With its unprecedented sensitivity, the huge observatory will resolve stellar populations of many galaxies beyond our Milky Way, obtain ultraviolet spectra of millions of individual sources and image cosmological deep fields four times faster than JWST does.

Detailed observations of supernovae and star-forming regions will shed more light on the so-called baryon cycle: the way in which the chemistry of the Universe gets enriched over time, eventually leading to the origin of life.

And in our own Solar System backyard, Habitable Worlds Observatory will be able to resolve details on large asteroids and planetary moons.

Are you excitied about the Habitable Worlds Observatory? Do you think this could be the mission to find life beyond our Solar System? Let us know your thoughts by emailing contactus@skyatnightmagazine.com.

This article appeared in the January 2025 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine