NASA's first Space Shuttle commander was on the Moon in April 1972 when news arrived that America’s first reusable spacecraft had been green-lighted for development.

“The country needs that Shuttle mighty bad,” astronaut John Young remarked. “You’ll see.” He was right.

After years of sending people into space in one-use-only capsules atop one-use-only boosters, programs like Apollo were unsustainable.

War in Vietnam and civil unrest at home convinced many that a cheaper way of shuttling people into space was needed. The Space Shuttle was born.

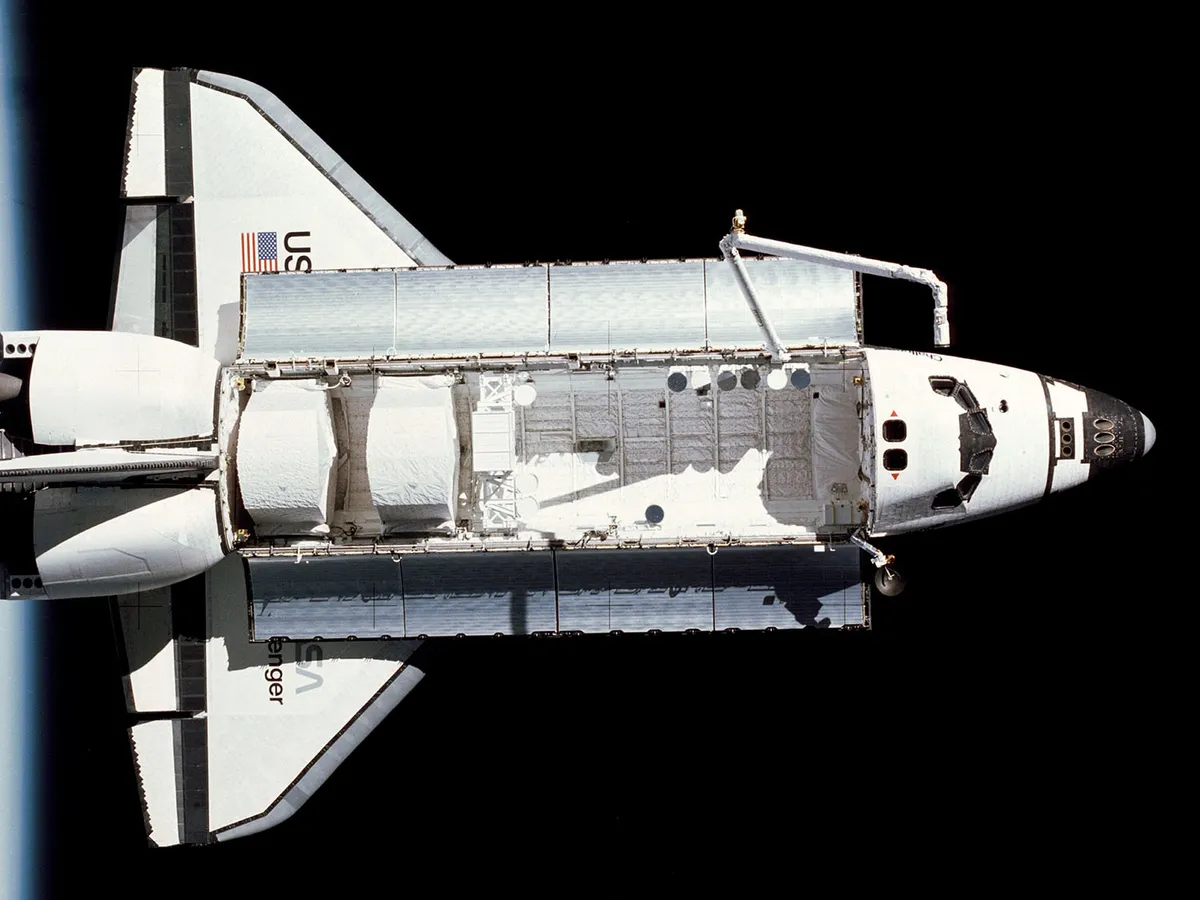

Delta-winged, of similar size to a DC-3 airliner, the Space Shuttle boasted a two-tiered cockpit and 60-foot-long payload bay to launch and recover satellites and perform wide-ranging research, from medicine to materials processing, solar physics to Earth sciences and technology to astronomy in Europe’s purpose-built Spacelab.

Aided by its Canadian robot arm, it advertised weekly missions with up to seven-member crews.

Space Shuttle astronauts worked from the ten-windowed flight-deck, whilst a mid-deck provided living quarters including galley, toilet and sleep stations.

But powerful Air Force support for the Shuttle came at the cost of a compromised design and the need to cater for military customers.

Launching the Space Shuttle

In addition to two launch pads at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, a military site at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California (eventually never used) was built for classified flights.

And despite being touted ‘reusable’, only the Shuttle and its twin solid-rocket boosters—which together produced 7.5 million pounds of liftoff thrust—were recoverable.

Launched like a rocket, the Shuttle glided unpowered to a 200 mph runway landing, whilst the boosters parachuted into the ocean for retrieval.

A 15-story external tank fed liquid oxygen and hydrogen to the Shuttle’s three main engines but was discarded after each flight.

On the pad, the 184-foot-tall ‘stack’ cut a peculiarly asymmetric figure; one astronaut likened it to a butterfly bolted onto a bullet.

Its technology proved notoriously difficult to tame, forcing NASA to fix problems with the main engines and thousands of heat-resistant tiles on its airframe to guard against temperature extremes of 1,650 Celsius during re-entry.

Those troubles, never fully resolved, would haunt the Space Shuttle in later life.

Problems with the Shuttle

Following several approach-and-landing tests with the pathfinder Enterprise in 1977, Young and Bob Crippen piloted Shuttle Columbia into space in April 1981: the first Shuttle spaceflight.

The Shuttle programme was declared operational the following year, but despite turning a profit by launching satellites commercially its veneer of respectability masked many cracks.

Heat-resistant tiles fell off during launch and the solid-rocket boosters showed worrying signs that hot gas was leaking through sealed joints.

One Shuttle suffered seized brakes and a burst tyre on the runway, another endured a main engine failure at the edge of space and an overstretched workforce was pressured to meet breakneck launch schedules.

Outwardly, NASA retained the bulletproof image of its halcyon Apollo days.

Astronauts flew jet-powered backpacks, captured and repaired satellites and by 1985 the four-strong fleet of Columbia, Challenger, Discovery and Atlantis - all named for seafaring vessels - was flying almost every month.

Then in January 1986, Challenger exploded 73 seconds into its flight, killing its seven crew members, which included schoolteacher Christa McAuliffe.

Blame fell on the solid-rocket boosters and a safety culture that one astronaut called “normalisation of deviance”.

Returning to flight in 1988, the Shuttle was never the same again.

Astronauts wore pressure suits and non-professional passengers - schoolteachers, senators, industry workers - were banned. The Shuttle would only be used when its capabilities were needed.

A new vehicle, Endeavour, replaced Challenger and the Shuttle launched several important payloads, including the Hubble Space Telescope, the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory and the Chandra X-ray Observatory, as well as the Magellan, Galileo and Ulysses probes.

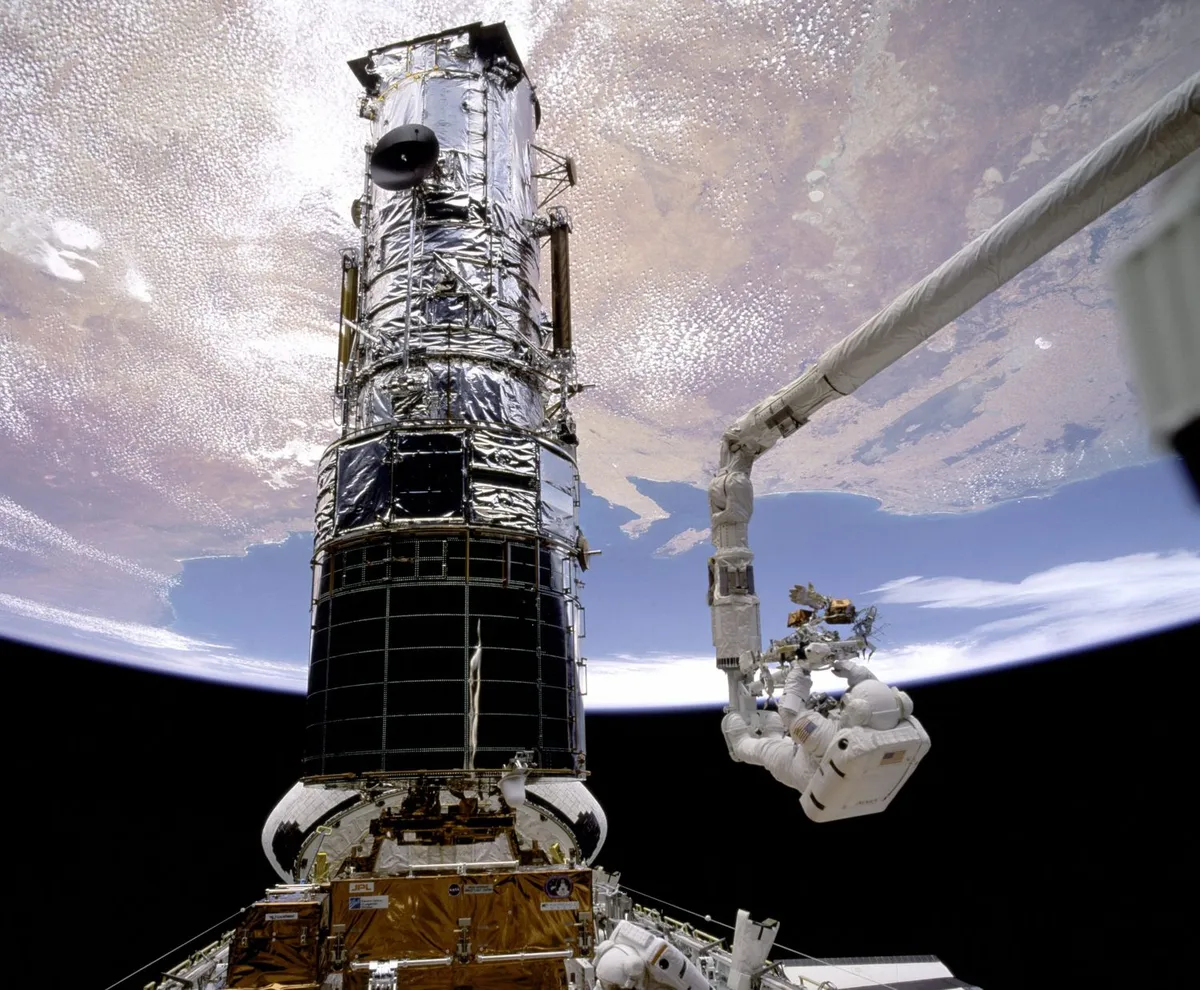

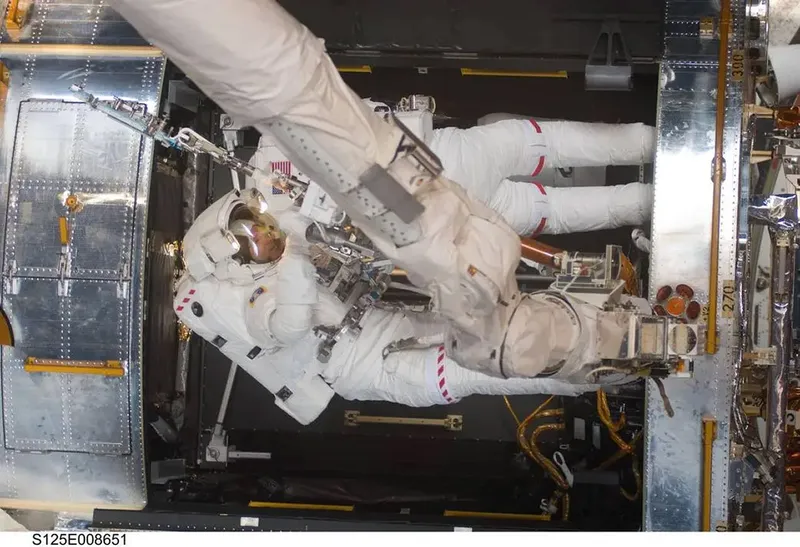

The Space Shuttle supported dozens of science missions and in 1993 space-walkers triumphantly fixed Hubble’s impaired vision; a defect that had only been discovered after the telescope's launch into Earth orbit.

In doing so, NASA and its astronauts about-turned negative public opinion and made the Shuttle ‘cool’ again.

Building a space station remained a fundamental goal, although its complexity and cost kept it teetering on the edge of cancellation.

But the collapse of the Soviet Union garnered hope that the Shuttle might, at last, have somewhere to shuttle to.

From 1995, it flew ten times to Russia’s Mir space station, delivering both astronauts and supplies, before work to assemble the International Space Station commenced in 1998.

Yet safety remained an issue for the Space Shuttle. Heat-resistant tiles still fell off; main engines kept failing.

In 1999, a crew came just one failure away from an emergency landing. Independent safety auditors warned that without substantial upgrades, the Shuttle’s lack of an effective escape system would doom a mission.

In October 2002, explosive bolts on Space Shuttle Atlantis failed to fire at liftoff; only their quick-acting backups saved the day. Another bullet was dodged in this high-stakes roulette game.

By now, the International Space Station was in orbit, permanently inhabited, but schedule pressures to complete it crept again into NASA’s mindset.

In February 2003, Shuttle Columbia was destroyed during re-entry.

This time the technical cause was a chunk of falling foam from the external tank, which struck and crippled the heat-resistant tiles during launch.

The crew completed their mission in space, yet during re-entry the damage that had been done caused Columbia to break up in the air, killing all seven crew members.

The surviving Shuttles returned to flight in 2005, but the programme's retirement was inevitable.

NASA pared down the remaining flights to service the Hubble Space Telescope once more and finish building the International Space Station, before the Shuttle’s wheels kissed the runway for the final time in July 2011.

Thirty years of service by five Shuttles cemented the credentials of this brilliant, albeit flawed machine.

Its 135 missions put 355 men and women from 15 nations into space and spent 1,323 days circling Earth 21,030 times.

It saw the first female commander, the first married couple, the first politician and the first royalty in space.

It set records for the oldest astronaut, the greatest number of missions by men and women and the longest-ever spacewalk.

Today, Discovery, Atlantis and Endeavour reside as museum-pieces in Washington, Florida and California, their monumental scale awing thousands of visitors daily.

The Shuttle never made good on its promise of weekly missions, yet these three retirees and their fallen sisters Challenger and Columbia wistfully remind us of a bygone era that forever changed our view of the Universe around us.

The Space Shuttle's legacy

The Shuttle was conceived to drive down the expense of throwaway, single-use-only spacecraft and democratise the experience of spaceflight for more people.

However, its results proved mixed.

Its five-orbiter fleet launched 10 times more people and spent four times longer in space than the Mercury, Gemini, Apollo and Skylab programmes combined.

But at $500 million per launch, flying the Shuttle was a monstrously complicated affair.

Even in its heyday, it achieved no more than nine annual launches.

Yet the seed of the idea of a reusable spacecraft was planted. That seed today continues its upward growth.

SpaceX routinely reuses its Falcon 9 rockets up to 20 times, with plans to extend that to 40 launches, flying dozens of times into space yearly.

Plans for a colossal crew-and-cargo-carrying Starship offer even more scope to bring down the cost of accessing space.

Since 2020, SpaceX has launched passengers on its fleet of four reusable Crew Dragons, one of which has flown five times, while two have logged over 18 cumulative months in space.

Boeing’s Starliner and NASA’s Orion are expected to bring whole or partial reusability into crewed Earth-orbital and lunar missions in the next few years.

Since 2021, Blue Origin’s New Shepard capsule has lifted six groups of humans to the edge of space.

These early flights furnish a taster of the kind of ‘regular-citizen missions’ originally envisaged for the Shuttle, with actors, television personalities and the first person with a prosthesis now being among those who have visited space.

Reusability has been an indispensable asset as this new generation of pioneers continues the slow but sure process of opening the experience of space travel to a broad demographic and furthering the democratisation of space.

And it all began with the Shuttle.

Space Shuttle key facts

Columbia

First flight: April 1981

Last flight: February 2003

No of missions: 28

Mission highlights:

- First Shuttle to fly in space

- Launched Spacelab microgravity

- Shortest and longest flights in Shuttle history

- Launched Chandra X-ray Observatory

- First female commander (Eileen Collins)

Challenger

First flight: April 1983

Last flight: January 1986

No of missions: 10

Mission highlights:

- First Shuttle spacewalk

- First American woman in space (Sally Ride)

- First African-American man in space (Guion Bluford)

- Bruce McCandless completes first untethered spacewalk: (F. Story Musgrave; Donald H. Peterson)

Discovery

First flight: August 1984

Last flight: March 2011

No of missions: 39

Mission highlights:

- First female Shuttle pilot (Eileen Collins)

- First sitting member of US Congress in space (Jake Garn)

- First member of royalty in space (Sultan bin Salman Al Saud)

- Launched Hubble Space Telescope

- First rendezvous with Mir space station

- First International Space Station docking

- Oldest astronaut (Mercury Seven astronaut John Glenn)

Atlantis

First flight: October 1985

Last flight: July 2011

No of missions: 33

Mission highlights:

- Last Shuttle to fly

- Launched Compton Gamma Ray Observatory and Magellan and Galileo planetary probes

- Highest orbital inclination ever reached by a Shuttle (62 degrees)

- First docking with Russian Mir space station

- Launched ATLAS microgravity science laboratory

Endeavour

First flight: May 1992

Last flight: June 2011

No of missions: 25

Mission highlights:

- First three-person spacewalk (Richard J. Hieb; Thomas D. Akers; Pierre J. Thuot)

- First married couple to fly in space (Mark C. Lee; N. Jan Davis)

- First African American woman in space (Mae Jemison)

- First repair of Hubble Space Telescope

- First and last International Space Station assembly missions

What are your memories of the Space Shuttle era? Let us know by emailing contactus@skyatnightmagazone.com