On 28 November 1966 the first Soyuz rocket blasted off from the Baikonur Cosmodrome, beginning a remarkable history that saw it become the the default vehicle for international spaceflight.

The Soyuz rocket development was ultimately a result of the Soviet Union’s desire to keep its foothold in the Space Race.

When US President John F Kennedy announced his intention to send a man to the Moon in May 1961, the Soyuz rocket was the Soviet response. It would, as we now know, outlive all other spacefaring rockets of its era.

More about the Space Race:

Sergei Korolev and developing the Soyuz

The rocket was developed in the early 1960s by space engineering firm OKB-1, which at the time was headed by Sergei Korolev.

The decade before, Korolev had designed the world’s first intercontinental ballistic rocket, the R-7, and this had already formed the basis for the development of the Vostok rocket – which carried Yuri Gagarin into space in April 1961.

From Vostok, he would create the Voskhod and Soyuz rockets, both within the space of five years.

This period also saw the development of two cosmodromes, Baikonur in Kazakhstan (at the time a Soviet republic) and Plesetsk in northwest Russia.

Korolev died in January 1966 and never saw the Soyuz rocket in operation. His creation was groundbreaking, especially in the way it launched.

The Soyuz three-stage launch

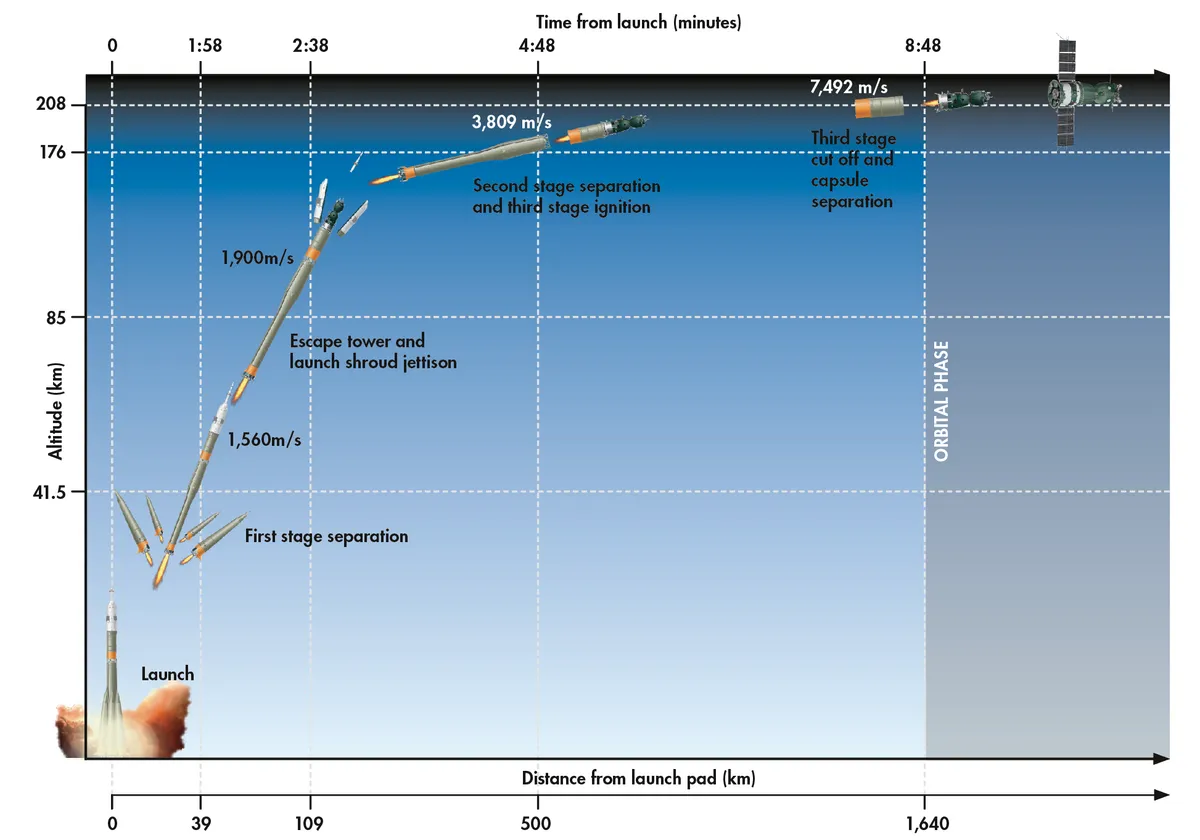

As a rocket uses up fuel, empty compartments create dead weight, so Korolev and engineer Valentin Glushko developed a three-stage launch process, enabled by a five-booster formation that lends the Soyuz rocket its distinctive flared shape.

During lift-off the four outer boosters consume their fuel, then detach when they are about 40km above ground, leaving a central core booster to carry the rocket upwards.

Shortly afterwards, the protective shield around the payload and the second stage rocket are both jettisoned, leaving the third stage, already 170km above Earth, to continue firing.

Once about 220km high, within low-Earth orbit, its last engine detaches and the Soyuz spacecraft (which bears the same name as its launch rocket) continues towards its destination.

Soyuz launch early days

It wasn’t long after its development that the Soyuz rocket was put to the test.

The US had already achieved the first docking of two spacecraft – one of which was unmanned – on 16 March 1966, and the Soviets were not to be outdone.

But their first docking attempt would end in tragedy. Colonel Vladimir Komarov launched on the Soyuz’s first manned mission on 23 April 1967 and was to dock with a second spacecraft, but complications caused the mission to be aborted.

Komarov attempted re-entry, but his spacecraft’s parachute failed to deploy correctly and he was killed as his capsule plummeted to Earth.

The next attempt occurred on 25 October 1968. Georgi Beregevoi managed to get within 200m of his target, but was unable to dock.

This endeavour was finally achieved on 16 January 1969, when Soyuz cosmonauts accomplished the first docking between two manned spacecraft, Yevgeni Khrunov and Alexei Yeliseyev passing from their spacecraft into another helmed by Vladimir Shatalov.

Soviet ambitions increased and so did the power of the Soyuz. On 24 November 1970, a Soyuz-L rocket carried the Soviets’ lunar lander into low-Earth orbit to prepare for a mission to the Moon.

The Soyuz-L featured reinforced boosters to carry the lunar lander and, although it made only three flights between November 1970 and August 1971, its design influenced the Soyuz-U rocket, which still serves the International Space Station to this day.

The Soviet space programme continued to expand with the Soyuz rocket at the centre of its ambitions, but tragedy was not far away.

On 22 April 1971, a Soyuz rocket transported three cosmonauts up to Salyut 1, the first space station of any kind, but they couldn’t enter due to a fault in the docking unit and the mission had to be aborted.

Docking was achieved on 7 June 1971 during the follow-up Soyuz 11 mission, but a malfunction during the return trip to Earth at the end of the month led to a sudden loss of atmosphere in the descent module, killing all three men aboard.

Cosmonauts Vladislav Volkov, Georgi Dobrovolski and Viktor Patsayev had been protected against the chill of space, but not depressurisation.

The disaster meant all future missions would require cosmonauts to wear spacesuits while in the spacecraft.

In July 1973, cosmonauts Alexei Leonov and Valery Kubasov visited NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Texas in preparation for Apollo-Soyuz: the first docking of spacecraft from different countries.

The metaphorical – and literal – shaking of hands between the two Cold War superpowers was a milestone for spaceflight.

The docking module was a combined US-Soviet effort, and each crew had learned the other’s language.

The Soyuz-U rocket flew its first manned flight on 2 December 1974 as a trial run for the Apollo-Soyuz mission.

The successful docking occurred on 17 July 1975, Soyuz commander Alexei Leonov greeting Apollo commander Thomas Stafford with the words “glad to see you”, to which Stafford replied “A, zdravstvuite, ochen rad vas videt” – Ah hello, very glad to see you.

The event was not enough to douse Cold War tensions, but the docking was nevertheless a precursor to the Soyuz rocket’s current use by many spacefaring nations.

Developments and upgrades continued throughout the decade, but a rocket with a history as long as the Soyuz cannot be without its hitches.

Commander Vladimir Titov and Gennady Strekalov came within seconds of tragedy on 26 September 1983, as they sat in the capsule atop a Soyuz-U rocket preparing for a mission to service the Salyut 7 space station.

Spilled fuel was to blame for the spacecraft erupting in flames, burning the control cables to its automatic ejector escape system.

Mission control manually activated the escape system, firing the spacecraft and its passengers 4km away from the towering inferno mere seconds before it exploded, saving the two cosmonauts’ lives.

Unshaken, the Soviets continued to send the Soyuz-U rocket into space and it would eventually deliver Expedition 1, the first resident crew to the International Space Station, on 2 November 2000.

Another major milestone in spaceflight history occurred in July 2011, when the American Space Shuttle fleet was retired.

From then on the five space agencies behind the ISS – NASA, Roscosmos, JAXA, ESA and CSA – have used Soyuz rockets to fly crews into orbit.

On 21 October in the same year, ESA launched a Soyuz ST-B rocket from its spaceport in French Guiana: the first to be launched outside the former Soviet Union.

Since its inception, the Soyuz rocket has been at the heart of space exploration; its durability a testament to Korolev and his team.

That it would one day become the go-to vehicle to carry both cosmonauts and astronauts into space would have been beyond Koralev’s comprehension.

Yet the Soyuz rocket has become not just a symbol of ambitious Soviet engineering or of Cold War technology, but of a united humanity, exploring the stars as one.

Korolev's legacy

What sort of a man was Sergei Korolev? We asked Doug Millar, deputy keeper of technologies and engineering at London’s Science Museum.

“Korolev was very much a pioneer, a remarkable man. He was the chief designer, a very good and able engineer, and that involved being able to manage many large organisations.

He knew exactly what was required and had the energy, the imagination and the foresight to see it through.

He had to marshal a large number of different design bureaux – engine designers like Valentin Glushko and Vasily Mishin – overseeing support systems, navigation, guidance, structures, and how to launch it.

No one had done this before; it was all new.

Resources, relatively speaking, were in far shorter supply in the Soviet Union than in the West, so they had to make do with what they had.

But if you look at the Soyuz rocket, it’s a beautiful design. It was initially designed to carry nuclear warheads, which it wasn’t very good at.

The problem was that it took long to fuel up – about seven minutes – so by the time you went to all that trouble, your enemy would have taken out your silo or launch site.

As a missile, it wasn’t very good, but as a space launch vehicle it was excellent and continues to be so to this day.

Korolev remained anonymous until after his passing in 1966, when he was given a state funeral, but there were reasons for this.

We shouldn’t forget that the Soyuz rocket’s development was taking place during the Cold War, and the Soviet space programme was really indistinguishable from its military.

It’s a tragedy he died in 1966, as I suspect he could have gone on to achieve even greater things.”

This article originally appeared in the December 2016 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.