If you've been following the latest discussions on the prospect of humans travelling to and colonising Mars, you'll be more than aware of the dialogue that's opened up between SpaceX founder Elon Musk and astrophysicist Neil DeGrasse Tyson recently.

DeGrasse Tyson appeared on the US talkshow Real Time with Bill Maher on 22 November 2024, and was asked about Musk's plans to colonise Mars and make it fit for human survival.

To put it mildly, DeGrasse Tyson was skeptical about both the reality and the reason for terraforming Mars and turning it into a human habitat.

Musk then responded to DeGrasse Tyson via X (formerly Twitter), stating that "Mars is critical to the long-term survival of consciousness."

But could humans really make the journey to Mars, and could we turn it into a habitable planet?

More to the point: should we? What are the ethical considerations of colonising Mars and making it fit for human habitation?

David A. Weintraub is professor of astronomy at Vanderbilt University, and is the author of On Mars: What to Know Before We Go, in which he explores the difficulties associated with getting humans to Mars.

Back in 2018 we spoke to Weintraub about humanity's fascination with the Red Planet, and how close we are to setting foot on its barren surface.

SQUIRREL_13161845

Why is humanity so fascinated with Mars?

From early telescopic studies of Mars several hundred years ago - really from the get-go of the invention of the telescope - astronomers discovered that Mars has a rotation period that is almost the same as Earth, just a bit more than 24 hours.

A few decades later, they discovered that Mars has polar caps and that it has seasons.

The seasons are longer than Earth’s because Mars’s year is longer.

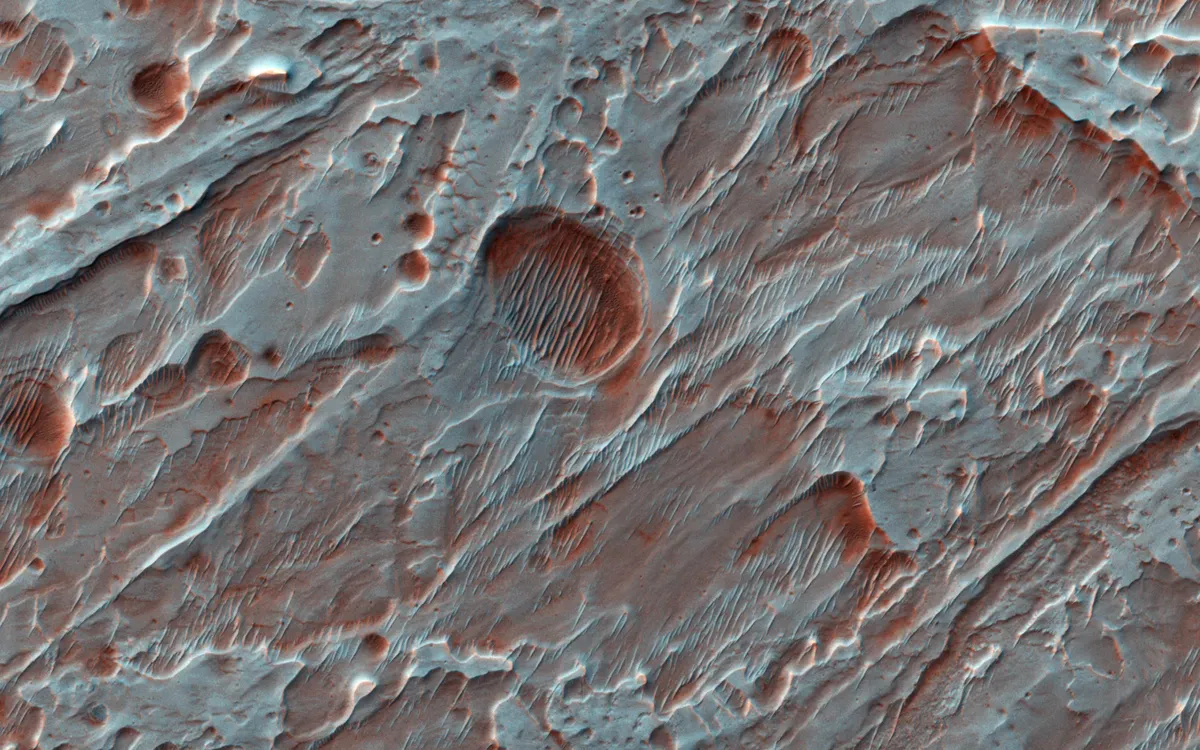

Mars’s rotation axis is tilted about the same as Earth’s, it’s a rocky planet with a solid surface and a thin atmosphere: these are all Earth-like qualities.

And Mars is far more Earth-like than any planet in the Solar System, which makes it so appealing.

Also, because it is so close, early astronomers with telescopes could more easily study Mars than other planets.

Venus is boring, because it has such thick clouds! We can’t see anything on Venus, even though it’s relatively near by.

Astronomers didn’t understand that until the 20th century, but they understood that they just couldn’t learn anything about Venus.

Jupiter and Saturn are much farther away, but Mars is close and it’s Earth-like.

Then in the 19th century in the early days of spectroscopy, astronomers 'discovered' - incorrectly I should point out - that Mars had a lot of water vapour, and appeared to have features on the surface that some 19th century astronomers decided were canals.

Mars does have water, but the 19th century observations that showed Mars had water were wrong!

Early astronomers thought Mars had vegetation too, didn't they?

They did! They certainly didn’t make any measurements that proved Mars has vegetation because, of course, Mars doesn’t have vegetation.

But the early observations of Mars in the 19th century were mostly focussed on the colours of Mars.

The dark colours were interpreted as vegetation, which is puzzling because the dark colours on the Moon are not interpreted as vegetation.

However, because astronomers already had in their minds an idea that Mars was Earth-like, they just decided that the dark colours meant plants.

The red colours seemed to indicate plant life on the surface, but these red colours are actually surface features and are also often dust storms.

As these dust clouds form and swirl around Mars, it could appear as if the vegetation was expanding across the surface, which they took to mean that it was growing rapidly.

What are the obstacles in getting humans on Mars?

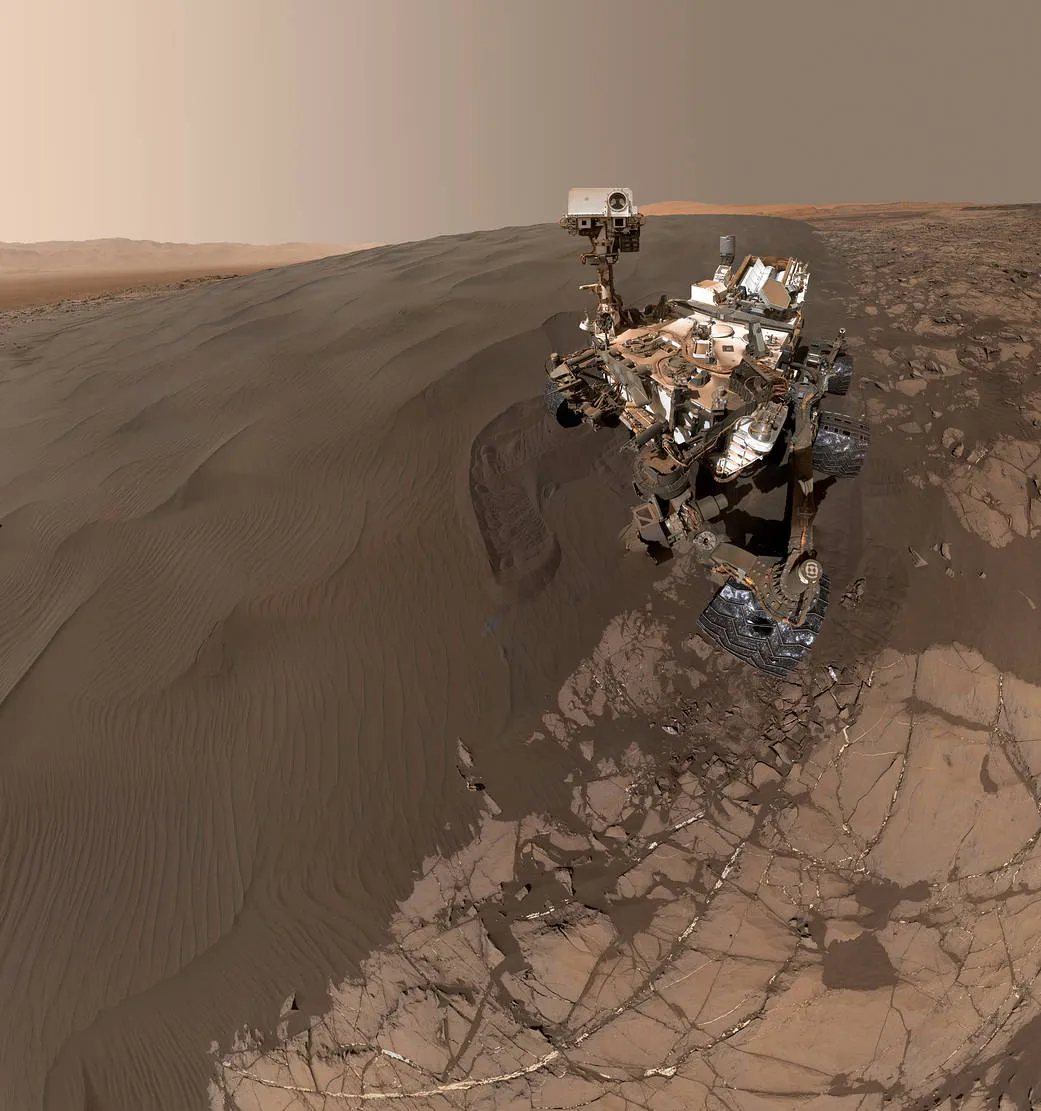

The main obstacle is building a rocket that’s big enough to send the pioneer astronauts, but which also has all the life support systems they need to keep them alive.

We’re good at sending rockets to Mars with rovers and telescopes, but those don’t have life support systems for astronauts.

They don’t have the food, the oxygen tanks, everything that is needed to keep astronauts alive.

What’s needed is a bigger rocket, but I think these bigger rockets are moving forward in the design phase.

We don’t need something bigger than the Saturn V that brought astronauts to the Moon a generation ago: it just has to go further.

The obstacles are less about getting astronauts there, than they are keeping them alive and getting them back.

They’re colonists who are going to Mars, they’re not adventurers who are going to Mars and planning to come home any time soon.

Keeping astronauts alive on the journey to Mars, I think, is doable.

Keeping them alive once they get to Mars for the long term: I think that’s a bigger challenge.

Would colonists on Mars would suffer from intense radiation?

That is the case. I don’t know offhand any estimates for how long someone might be able to stay alive, but the radiation from the Sun is very dangerous.

Some of those solar flares are impossible to avoid, and at the moment I don’t think we have the technology to shield astronauts in deep space from the intense energy of those solar flares.

I think a tremendous amount of research is being invested in figuring out how to enable astronauts to survive the harsh radiation environment of space, and on the surface of Mars it’s not much better than being in space in orbit around Mars.

And you’ve got to be able to survive that harsh environment for very extended periods of time.

We don’t know how to do that yet.

Could we grow food on Mars?

I think The Martian movie was a great depiction of one imaginative way that could be done.

I think growing food on Mars is possible.

There are experiments already looking at growing food in space on the International Space Station, or how to grow food using a concoction that what we think Martian soil must be like.

I think it’s possible, but can we grow enough food, and quickly enough? I think the resources exist on Mars: we’ve got sunlight, carbon dioxide for plants, water.

You don’t need much more than that if you can actually get the process started.

You could imagine dropping habitats onto the surface of Mars, inside of which you could grow plants, you could have grow lights, you could manufacture soil.

I think it’s possible, but for how many people and for how long? These are serious problems that have to be solved.

Are there ethical considerations around humans colonising Mars?

I think there are two very different ethical considerations.

One is that, if we send colonists to Mars, can we keep them alive? If not, then I think we have an ethical problem in sending them.

If we can keep them alive and bring them home safely, that’s a different story.

But if they’re just going to Mars to die, or if we’re sending them to Mars and we don’t have high expectations that we can keep them alive, I think that’s a seriously ethically compromised vision of what we should be doing.

The second consideration is whether we should be contaminating Mars. When we set food on Mars and start growing food, when we put substantial amounts of our DNA on the planet, we will contaminate it.

If Mars is a desert like the Moon, if it is sterile, then I think it doesn’t matter. If we’re just talking about landing on a rock with no life, then I don’t think there are any ethical issues.

I think we have to figure out whether there is any life on Mars before we land on the planet and try and colonise it.

But if there is indigenous life, we have to think very hard about whether we have the right to colonise Mars.

If you look at the Cassini spacecraft at Saturn, we de-orbited it into the planet because of the risk of allowing Cassini to crash into Titan or Enceladus.

These are two moons of Saturn of which we know little about, other than that there is a possibility that they could harbour life because of their chemical makeup and the presence of liquid.

We don’t want to contaminate those worlds where there might be life, but Mars is an even better possibility for some kind of life, and we’re not talking about protecting Mars in the same way. I find that surprising.

What would we do once we get to Mars?

The main thing would be proving that we can live on another planet.

Learning how to grow food, how to manufacture the energy needed to survive, how to find water and melt it to survive: those are the first steps.

A second obvious step would be what science fiction writers have always called 'terraforming': trying to make Mars more hospitable for us.

The atmosphere is almost entirely carbon dioxide, which is good for plants, but not for us.

So unless we’re just going to live in tents on Mars, we need to change the Martian atmosphere. I think most of the initial projects would be survivability.

Beyond that, Mars also has a lot of mineral reserves, which a lot of countries and companies on Earth would probably love to get their hands on!

Mars colonisation plans. Credit: Victor Habbick Visions/Science Photo Library/iStock/Getty Images

Would you go on the first trip to Mars?

A little bit of patience would enable us to reach the point at which our technology would give us confidence that an astronaut going to Mars is not sacrificing themselves.

When the early European explorers sailed to the ‘New World’, they were taking risks, but they didn’t think they were intentionally going off to die.

I wouldn’t put myself in that situation, and I think with a little bit of patience we will be sending people off with a good chance that they will make it back.

Assuming my two ethical considerations were out of the picture, and that I could survive and come home, and that I were confident we had explored Mars and made sure it is sterile with no native life, then yeah I’d be eager to go!

I can’t think of anything more exciting than being one of the first humans to step on Mars. It’s a fascinating possibility.

Do you think we could or should colonise Mars for human habitation? Let us know your thoughts by emailing contactus@skyatnightmagazine.com

This interview was conducted with BBC Sky at Night Magazine in 2018.