The Cassini-Huygens mission will be long remembered for its amazing study of Saturn and its moons, including the Huygens lander's incredible landing on moon Titan.

Long before NASA's Dragonfly mission, in 2005, the Huygens lander touched down on Titan.

ESA’s Huygens probe hitched a ride to the Saturn system on NASA’s Cassini orbiter.

Primarily designed as an atmospheric probe, Huygens descended towards Titan by parachute on 14 January, taking 2 hours 27 minutes to reach the surface.

Throughout the journey, it measured how the composition, temperature, pressure and air density varied with altitude.

These measurements will prove invaluable to the upcoming Dragonfly mission as mission scientists try to ensure their own spacecraft safely makes it to the moon’s surface.

Huygens images of Titan

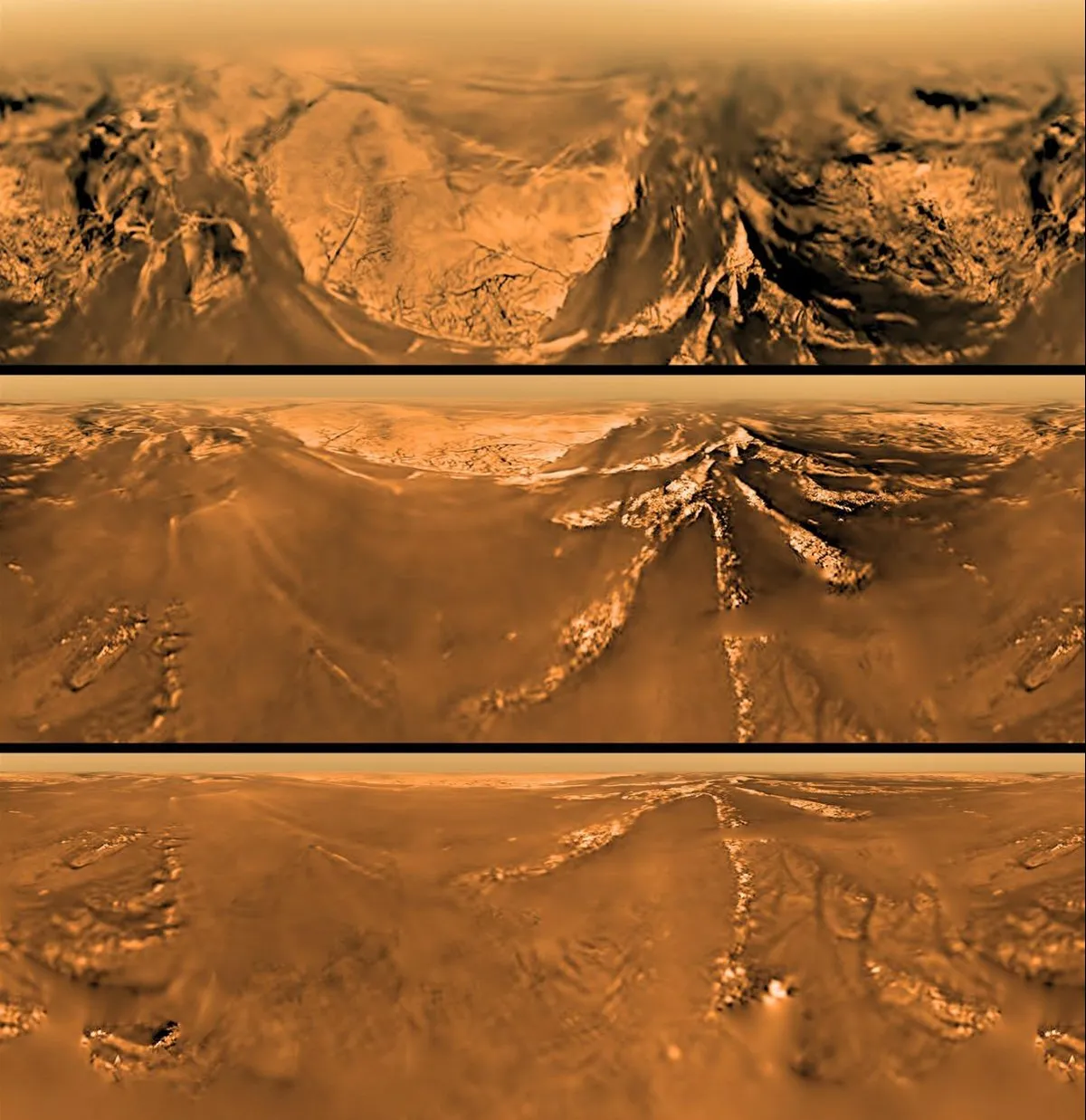

Huygens took many images as it approached the surface of Titan, building a map of the terrain surrounding the probe’s eventual landing site.

The images revealed a sandy landscape scattered with rounded pebbles in what is now thought to be a dry lake bed.

The lander transmitted its findings to Cassini for 70 minutes, until the orbiter moved beyond the horizon, out of radio contact.

Cassini relayed the data home, only for the mission team to discover that a coding error meant half of Huygens data hadn’t been recorded!

Even so, the half that was saved revealed a fascinating world that planetary scientists have been itching to return to for the last two decades.

This article appeared in the August 2024 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine