Jack in his Reserve Officer Training Corps uniform at the University of Florida in 1962. That year, Jack would hear Kennedy's 'we choose to go to the Moon' speech, and decided to pursue a career in spaceflight. Image Credit: Jack Clemons

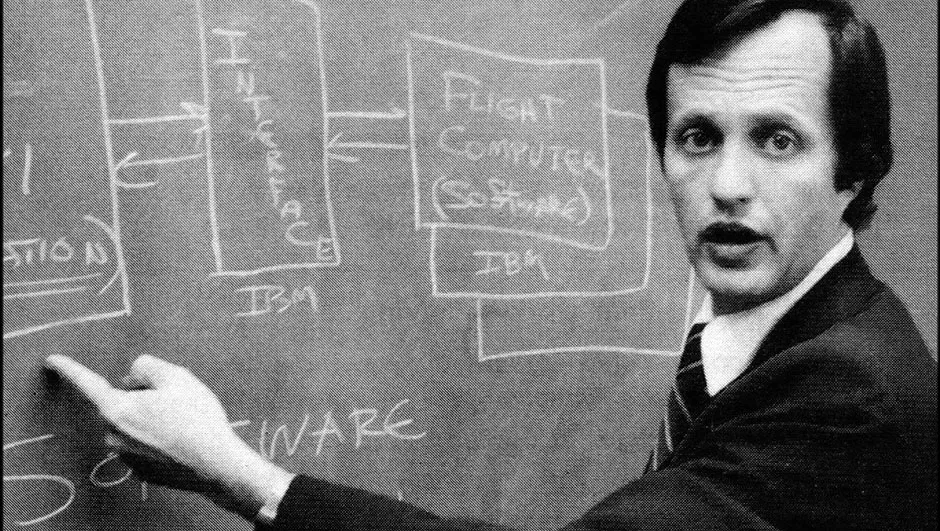

How did you get involved in the Apollo programme?

My background is aerospace engineering, in which I have a Masters degree, and when I was young I used to read a lot of science fiction.

When I got to college I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do with my life; maybe be a writer.

Back then I guess I thought I could make a living out of it!

I went to the University of Florida and around that time John F Kennedy made his speech ‘we choose to go to the Moon, not because it’s easy but because it’s hard’ and it just enflamed me. It was wonderful.

The University of Florida had just started its aerospace engineering programme, so I got my degree and then ended up working for a general electric division up in Pennsylvania.

As it happened, the Apollo 1 fire delayed the programme enough that when they restarted it, I had the opportunity to take a job down in Houston, Texas, right across from the Space Center and put my aerospace background to work.

My speciality was high-speed aerodynamics, which relates to asteroids coming through the atmosphere, or guided missiles coming through the atmosphere, or Apollo Command Modules coming through the atmosphere! So that’s what they assigned me to.

I worked reentry for Apollo and the contract we had was with a company called TRW Systems.

They now make auto parts, but back then everybody was in space.

NASA had a whole team of contractors that supported them, so their arms and legs were much more than just NASA employees.

I was assigned to the folks over there that supported reentry and when I first sat down at my desk, Apollo 7 was already overhead.

I worked all the way from Apollo 8 to Apollo 17, which was seriously cool.

Then TRW lost the contract for the Shuttle programme, but IBM had just won the contract to build all the onboard software for the Space Shuttle.

They realised they needed engineers, not just programmers, so they hired about 50 of us and we came from TRW, literally down the street!

It was about two blocks away.

I worked on onboard software for the Space Shuttle until about 1984.

Your book Safely to Earth is subtitled ‘The Men and Women Who Brought the Astronauts Home’.

Who are the titular men and women?

I took a lot of engineering notes back in those days and I still have them, so when I decided to write this book I was able to pull up information that I hadn’t looked at in years.

My agent at one point, asking me to expand the book, asked “didn’t you work on the Skylab project at one point?” and I said “I don’t think so!”

But I went back and looked at my notes and sure enough! In fact I had a certificate saying so.

That’s where the book began, and it was intended to be a memoir about my time on Apollo and the Space Shuttle.

But as I got into it, what it really turned out to be about was the people I worked with.

That’s the focus of the book. It’s all written in the first person so I’m obviously in there, but I talk about the kind of jobs we had and why we did them, and I try to turn it into plain English rather than tech-talk.

But also I feature a lot of the people - both on the NASA side and on the contractor side - that I worked with.

When I started out in this business there was probably one woman who had a technical background, and as time went on, the number of women started growing.

But on Apollo, it was almost all white men: probably a couple of women.

When I got to IBM the organisation I joined was probably about 60 per cent women.

I don’t know if you saw the movie Hidden Figures, but something analogous had happened.

I wasn’t taught programming when I was in college: I didn’t even know how to do that.

Then suddenly I was in an area where programming was everything and a very large number of young women who had a background in mathematics decided to go into programming.

Virtually overnight it changed from working with maybe about three women to working with about 60.

Both men and women: it was an astonishing group of people.

What would you and your colleagues be doing on a day-to-day business?

Our teams were supporting every phase of the mission, from launch to landing, to the activities on the Moon.

The onboard guidance system was already there: there was an automated guidance system onboard the Command Module, although it fairly primitive!

But the worry was, if it’s not working, what do you do?

In my case during reentry we had to build a set of things called ‘reentry monitoring and backup control procedures’.

Each crew would have a check list that they had to look at as they were coming in during reentry.

Based on that, we would decide whether to proceed with reentry, or if there was something seriously wrong you had to take over and fly it manually.

All of that was in each of the documents, one of which was written for each mission.

The idea was to provide that kind of planning in advance.

We would brief the crews, especially the Command Module Pilot, because they flew reentry. On Apollo 11, for example, it was Michael Collins.

That was their job and they would fly reentry simulators and try various simulations, and we had access to the simulators as well.

We didn’t fly the spinning ones like something out of Disney World, ours was more like an arcade video game but it had an Apollo computer in it.

We would get in there and take turns. I would be sitting in the Command Module seat and my teammates would give me a real reentry or a problem reentry, but I wouldn’t know which one it was.

I’d be watching all the displays and thinking “oh, this doesn’t look good!” then take over the system and land it.

Of course we weren’t actually moving anywhere so there wasn’t much at risk, but then the crew would train with that.

During the mission, depending what was going on, we would also be in the back rooms at Mission Control.

So those big displays you see from time to time at NASA Mission Control: behind that is a whole other set of offices, rooms and support rooms.

We would be in there and a controller that had responsibility for reentry would be on the main console, and if they had any questions then they’d call one of us and we’d be back there trying to help them figure out what to do.

Because of that I ended up working Apollo 11.

Apollo 8 was the first time humans circumnavigated the Moon. What was that mission like to work on?

Scary! There was an odd set of things that happened.

NASA was very careful about doing a step-by-step approach to landing on the Moon.

Clearly we were all worried about doing it the first time and ‘beating the Russians’, or whatever!

Apollo 7 was about taking the Command and Service Module - no Lunar Module - and testing it in Earth orbit.

Apollo 9 was about taking the Command and Service Module and the Lunar Module and testing it in Earth orbit.

Apollo 10 was taking everything up to the Moon, circling it, going down to the lunar surface but not landing, then coming back, like a complete dress rehearsal.

Then, of course, Apollo 11 was landing on the Moon.

The worry was that the Russians were going to beat us, and we’re not sure any more why that would’ve been a bad thing.

So where did Apollo 8 fit in?

There was a fair amount of nervousness that the Russians were going to beat us, so it was a case of “maybe we ought to at least orbit the Moon” and do that first.

They reprogrammed Apollo 8 so that it went to the Moon, circled it on Christmas Eve for several orbits and then came back.

This was our opportunity to go up and be the first humans, at least, to go around the Moon. But this was only the second flight, so it was kind of risky!

Furthermore, on Apollo 13 the Service Module blew up so the astronauts had to climb into the Lunar Module to save themselves.

There was no lunar module on Apollo 8: it wasn’t ready. Had the same thing happened on Apollo 8, we would have lost those astronauts.

All of the Apollo missions were scary though.

Looking back you think “oh yeah, we went to the Moon” but we were launching the missions every three months roughly.

Apollo 17 was 1972; Apollo 7 was 1968, so there really wasn’t that much time between missions.

It was all over in four years.

The big deal was getting to the Moon before the decade was out. Apollo 11 obviously did, but Apollo 12 did also.

It got there before the end of the year, because the concern was that if Apollo 11 couldn’t land, we would have one more in the queue so that JFK’s promise could be fulfilled.

Then things stretched out a little bit and the missions were about six months apart, but it’s still hard looking back on it now and seeing it all happened in about four years.

It feels much longer!

Why do you think the Apollo missions were so prolific?

The worry was that the Russians were going to beat us, and we’re not sure any more why that would’ve been a bad thing.

I don’t know what we thought they were going to do once they got up there: throw rocks at us or something!

But that was the big worry. So it was wrapped around this whole Cold War Space Race and that it would be our advantage to not let the Russians get there first.

Because Kennedy had said we would put a man safely on the Moon and return him to Earth by the end of the decade, when it finally happened public interest in the Apollo programme dropped off entirely.

Apollo 11 was a big deal; almost nobody watched Apollo 12. Apollo 13 they didn’t even cover live until they found out we had a problem.

If somebody said for old time’s sake we’re going to go back to the Moon using old 1969 technology, I wouldn’t sign up!

By that stage we were in the middle of the Vietnam War, and there were lots of other things that the nation was worried about.

They cancelled the last three missions all together and repurposed the spacecraft for the launch of Skylab.

In all of human history, humans have been looking up at the Moon, going “what is that thing?”.

Here was the first time in history we could ask the question “should we go back to the Moon?” and the answer was “nah!”

Do you think we should go back to the Moon?

Humans will definitely go back to the Moon. Whether or not they’ll speak English I don’t know!

Whether they’ll be flying a British flag or an American flag I don’t know.

But there seems to be something built into our DNA that says ‘we must go explore’.

I guess it goes all the way back to early humans, who said “let’s get away from the campfire and see what’s over that other hill.”

Ultimately, I think a number of us will need to get off this planet, particularly with the asteroid threats.

These are just being talked around and no one’s taking them seriously enough.

If a big one hits Earth, we could be set back quite a bit, if not wiped out altogether, so I think there is an imperative to get back to the Moon.

Should we go? Yeah, I think so. I’ve always been a science fiction fan so I’d say “you bet”.

But when you think about it, we were lucky. We had the Moon close by, and it was big. So that was a nice first step.

Space is airless, meaning there were a bunch of problems we didn’t have to worry about.

The next step, I think, would be an asteroid rendezvous.

It’s between us and Mars, it's a much more complex piece of aerodynamics and spacecraft manipulation, it challenges us in a way that landing on another planet wouldn’t and it’s kind of an intermediate step.

What I think will happen is that the commercial enterprises will ultimately achieve this.

Was there a lot of tension during the Apollo missions?

In retrospect we know we were successful but at the time we didn’t know we would be, so the tension was there on every mission.

Neil Armstrong was the perfect astronaut.

He just would not be flustered and turned out, in my opinion, to be exactly the right person to send to the Moon first.

Also as it happened he was a civilian at the time so it meant we weren’t putting down boots on the ground.

During Apollo 10 when they came down and approached the lunar surface but didn’t land, then came back up, they spun out of control briefly right above the lunar surface.

But they got control of it, and then were able to fly back up and I was thinking “what the heck was that?”

They brought the descent stage down to just above the surface, then they jettisoned the descent stage and came back up.

If they had been sitting on the Moon’s surface when they did that they would have spun right into the the ground.

The concern for Apollo 11 was whether they had the problem fixed: I wasn’t working on that part of the programme so my anxiety was even higher!

Apollo 13 in my mind was as important a technological feat as 11 was.

This was reality: we had to figure out whether we could take the limited capability that we had.

It was a completely out-of-the-blue problem, but we had to solve it and ultimately save the astronauts, and they had to go all the way out to the Moon and back in order to be saved.

It was very tense.

If you saw the movie Apollo 13, right towards the end there’s a brief mention of a reentry blackout.

When they’re coming back into Earth’s atmosphere, it’s going so fast and it’s so hot that all this radio static builds around the Command Module and you can’t communicate with them.

The worry we had was that the explosion on the Service Module had blown up right behind the heat shield, so if the heat shield was damaged these guys weren't going to come out of it.

There was no way of knowing. You can’t climb out and examine it as it’s attached to the Service Module.

Besides which they were all so weak they wouldn’t have been able to get out to do it anyway.

They were coming in to reentry and during reentry there’s a two to three-minute blackout, so we wouldn’t know until that three minutes was up whether or not they were alive.

Two to three minutes turned into almost five, and we were sick.

I was working the back room at that time and we were thinking "they’re gone".

My stomach still hurts, thinking about it.

Of course then they came back to us and were all nonchalant - “OK we read you” - and they were fine, but yeah that was really really scary.

What sort of equipment were you using at Mission Control, and can you compare it to what NASA uses now?

Technology was old compared to today, or even the Shuttle, but at the time it was the best we had. We made up the difference with people: a lot of training, a lot of procedures.

We did have some fairly advanced computers on the ground: IBM mainframes that IBM actually built and supplied for Mission Control.

With those we could simulate most of the mission so that during the actual mission you had these computers crunching along, telling us how it was going and what needed doing.

There was a lot of manual work onboard the spacecraft too to make it work.

But if somebody said “for old time’s sake we’re going to go back to the Moon using old 1969 technology” I wouldn’t sign up!

The amazing transition was with the Space Shuttle.

On Apollo we had a fairly primitive guidance computer, relatively speaking, and we were using slide rules and making sure if something happened we would know what to do.

But virtually every system onboard the Space Shuttle was driven by the onboard computer. In fact the crew in many cases couldn’t fly it because it was so dynamic.

When this thing was lifting off the ground with its wings hanging out, you’re not going to be able to grab the stick and fly it. It has to be done entirely by the computer.

Same thing during reentry. The Shuttle’s coming down at a terrific speed, and the crew doesn’t grab hold of the stick and say “you know I think I’m gonna fly this thing myself” because you could end up spinning it out.

In fact the computers would even restrict what the flight crew could do. If they made a command that was going to cause a problem, the computer wouldn’t execute it.

I got to NASA in 1968 and by 1974 I was working on the Shuttle, and a huge technological transition had occurred.

We certainly weren’t using slide rules any more: the handheld calculator finally came in from HP!

The Shuttle itself continually evolved over its life cycle. They kept adding more and more upgrades on the technology.

When you look back on Apollo, what do you think was its lasting legacy?

When Neil Armstrong stepped out onto the Moon, the reaction around the world at that time was ‘we did it’, meaning ‘we’, not meaning the United States.

Humans had put another human being on the Moon. We had gone to that god in the sky and now we were walking on the surface.

It’s become kind of a touchstone: you hear people say “we can put a man on the Moon but we can’t work out how to make our transit system work,” or whatever!

But as time goes on, it also becomes like a lost race story or something. What has happened to us?

My book is an example. I’m getting lots of interest in it.

Whenever I talk, there’s lots of interest: people want to come and hear about it, about what it was like.

There’s a hunger for this adventure, for this thing we did back in the day that we don’t seem to be able to do right now.

I think it calls to us, in the sense of a desire to get out there and do the impossible, to be proud of what we as humans can do.

I was at the World Science Fiction Convention in San Jose, California, and I had a talk at 11am on a Sunday, which I was not too excited about!

I’m not one of the big science fiction writers, I’m just me! I went into this room thinking “oh God, I hope five or 10 people turn up otherwise it’s going to be really embarrassing.”

There were about 130 people; in fact many of them couldn’t get in because so many wanted to hear about Apollo and hear me read from the book. They wanted me to talk about the programme.

There’s a tremendous amount of interest and I think it’s archetypal almost.

Right now I think we’re not very happy about a lot of things the government does anyway, so it’d be nice to look back at a time that’s almost imaginary now.

When I was asked at one point "what’s the best thing that came out of the programme?" I said “me”.

I was a guy who wasn’t going to be in engineering; I wasn’t going to be in science. God knows! I’d probably be working in Walmart writing science fiction.

When Kennedy rallied us, a whole young generation got into the sciences, got into technology, and of course not all of them went into the space programme.

There was an uplift of interest in science and technology that has subsequently faded again. People now want to be lawyers I guess!

It brought about an energy to get engaged in sciences and adventure, and I think it’s like our origin story.

We sit around the campfire and talk about our ancients that went on fiery rockets up to the Moon and people say “oh no that couldn’t have happened,” like all the deniers. “No, no that was all done in Arizona!”

I think it’s a call to adventure that’s very very deep.

Jack Clemons' book Safely to Earth,published by the University Press of Florida, tells the story of the men and women who worked on the ground making sure the Apollo and Shuttle missions were successful.

Jack Clemons was speaking to Iain Todd for BBC Sky at Night Magazine.