Former NASA astronaut Kathryn Sullivan spent a career forging new ground in science and spaceflight. On 11 October 1984 she became the first US woman to spacewalk, and in April 1990 she was part of Space Shuttle crew STS-31, which deployed the Hubble Space Telescope into Earth orbit; arguably one of the most groundbreaking scientific achievements of the century.

In 1992 Sullivan was the Payload Commander onboard Space Shuttle Atlantis on a mission to place the Atmospheric Laboratory for Applications and Science (ATLAS-1) experiment on the Spacelab space station.

She logged over 532 hours in space in total, before retiring from NASA in 1993.

She is without a doubt one of the most influential astronauts in the history of spaceflight, and an inspiration for many of today's women astronauts.

Sullivan's book Handprints On Hubble is a memoir of her days as a NASA astronaut; in particular the mission to launch the famous space telescope and, in doing so, help usher in a new era of astronomy.

Freed from the restraints of Earth's obscuring atmosphere, the Hubble Space Telescope gave astronomers an unprecedented view of the cosmos, leading to an increased understanding of the workings of the Universe, its past and potential future.

BBC Sky at Night Magazine got the chance to ask Sullivan about her experiences working on the Hubble mission, what it was like to float in space, and the legacy of NASA's Space Shuttle.

What led to your decision to become an astronaut?

A love for maps and the adventures of explorers like Jacques Cousteau and the early astronauts combined with my own curiosity to make me long to have similar adventures, and to get to know the world as richly as they seemed to know it.

This longing led, eventually, to my becoming an oceanographer and undertaking a number of major deep-sea expeditions.

These provided the academic foundation and operational experiences that made me a viable candidate, when NASA began the search for Space Shuttle astronauts.

The rest is timing: I had nearly finished my PhD and was not yet committed to a next career step.

What does it mean to you to have been responsible for putting Hubble in orbit?

I do not claim personal responsibility for putting Hubble into orbit. If anybody could make such a claim, it would be the man who pulled the trigger to set Hubble free from the shuttle’s robotic arm, my STS-31 crewmate Steve Hawley, and not even he would make that claim.

It was a team effort, both aboard the Shuttle and in mission control back on Earth.

Hubble transformed astronomy scientifically and socially, changing our understanding of how the Universe works and our place in it.

I am tremendously proud to have been part of that team, and consider that my role gives me a claim on every spectacular image and remarkable scientific finding that Hubble has given us.

I had the privilege of playing an important role in the launch of one of the major scientific revolutions of our times.

Did Hubble's deployment all go smoothly, or were there any scary moments?

Deployment day was an intense affair from start to finish and we had several anxious moments, but none that was scary in the sense of feeling we were in jeopardy.

Hubble had risen smoothly up from its berth in all our simulations, riding smoothly on the end of the shuttle’s robotic arm.

In orbit, it began to sway left to right as soon as Steve Hawley began to lift it.

This was a huge worry, because the telescope filled the cargo bay with mere inches to spare. Any bump could damage Hubble’s sensitive equipment.

We all breathed a big sigh of relief when the telescope finally cleared the cargo bay walls completely.

We had another anxious moment soon after that, when the second of the two large solar arrays jammed while being unfurled from its spool.

Hubble could not survive without both solar arrays deployed fully, and its batteries could only last a few more hours with a partial deployment.

We had prepared for this eventuality, with my crewmate Bruce McCandless and I spring-loaded to don our spacesuits and go outside to crank the solar array out by hand.

We started down that path, while the team on the ground tried to figure out what had gone wrong.

Luckily for Hubble, they figured out it was an instrumentation problem and were able to fix it with a software command.

This was unlucky for Bruce and me, however. We were were stuck in a partially-depressurised airlock – halfway between the Shuttle’s cabin and outer space.

Instead of doing a spacewalk and witnessing Hubble’s deployment, we could only listen as the final events unfolded.

How did it feel when you heard about Hubble's faulty mirrors? Did you feel a desire to get back up there and help with the repairs?

It was a crushing disappointment; the rug pulled out from under me.

I think we all had been imagining how spectacular Hubble’s 'first light' image would be, and the awe and pride we would feel when we saw it; now, nothing.

I came across a great description of the feeling during my research: Arthur Fisher wrote in Popular Science: “It was as if an eagle had become a bat.”

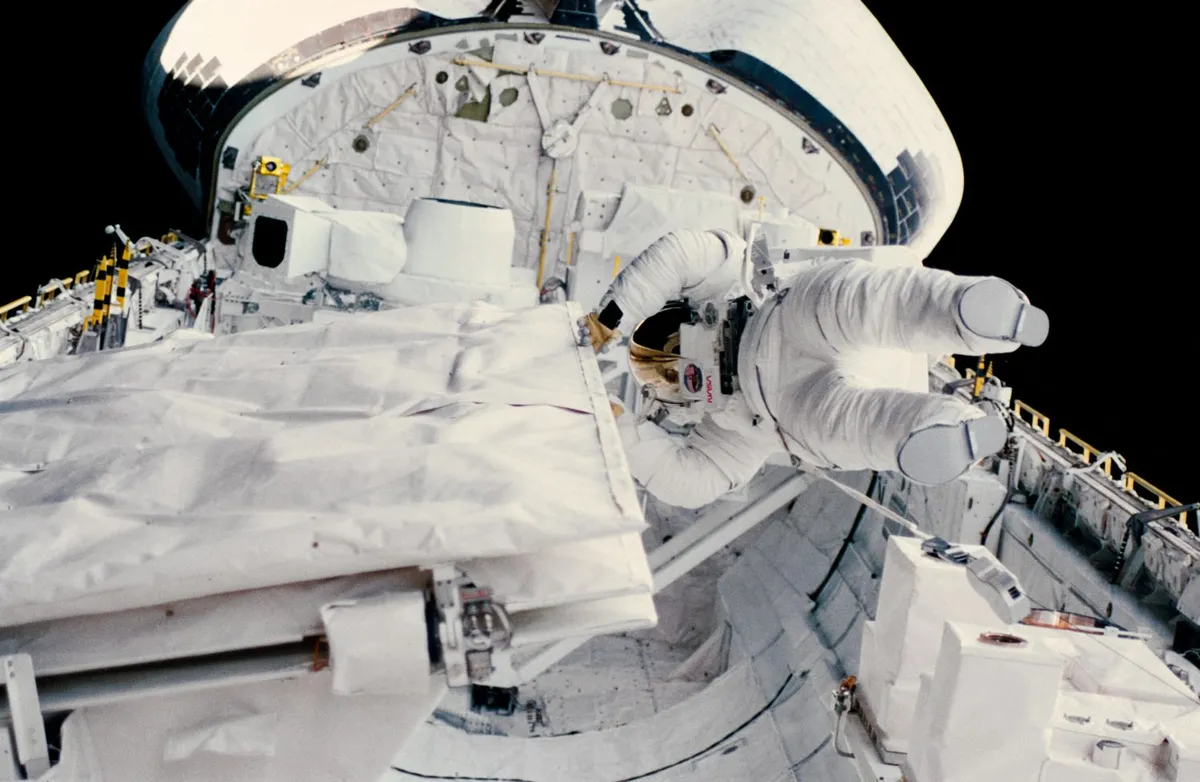

You were the first American woman to spacewalk. Can you describe the physical sensation of performing an EVA?

Imagine being able to 'swim' anywhere in a room with just the touch of a finger, with no sense of falling being right-side up or upside down.

The freedom of movement is positively magical, even when wearing a spacesuit that weighs over 300 pounds on Earth (although it weighs nothing in orbit, it still has considerable mass, which you learn to account for as you move).

How do you feel when you look back on the Space Shuttle era?

In 1969 I watched the Apollo 11 landing as a freshly-minted high school graduate. In 1978 I arrived at the Johnson Space Center as one of the new batch of astronauts.

I’m still amazed that in the span of nine years I went from being a spectator to a participant in the grand adventure of human spaceflight.

Our class got to help put the Shuttle into operation and fly many first-ever missions, like satellite retrievals and repairs.

The Shuttle was a remarkable, first-of-a-kind machine that pushed the envelope on a number of technologies and let the United States learn how to live and work off Earth for extended periods of time.

People who carp that the Shuttle didn’t live up to its early hype or became ho-hum sell the vehicle short and underestimate the value of the experience base it gave us.

What do you think, ultimately, is the Hubble Space Telescope's lasting legacy?

It transformed astronomy scientifically and socially, changing our understanding of how the Universe works and our place in it.