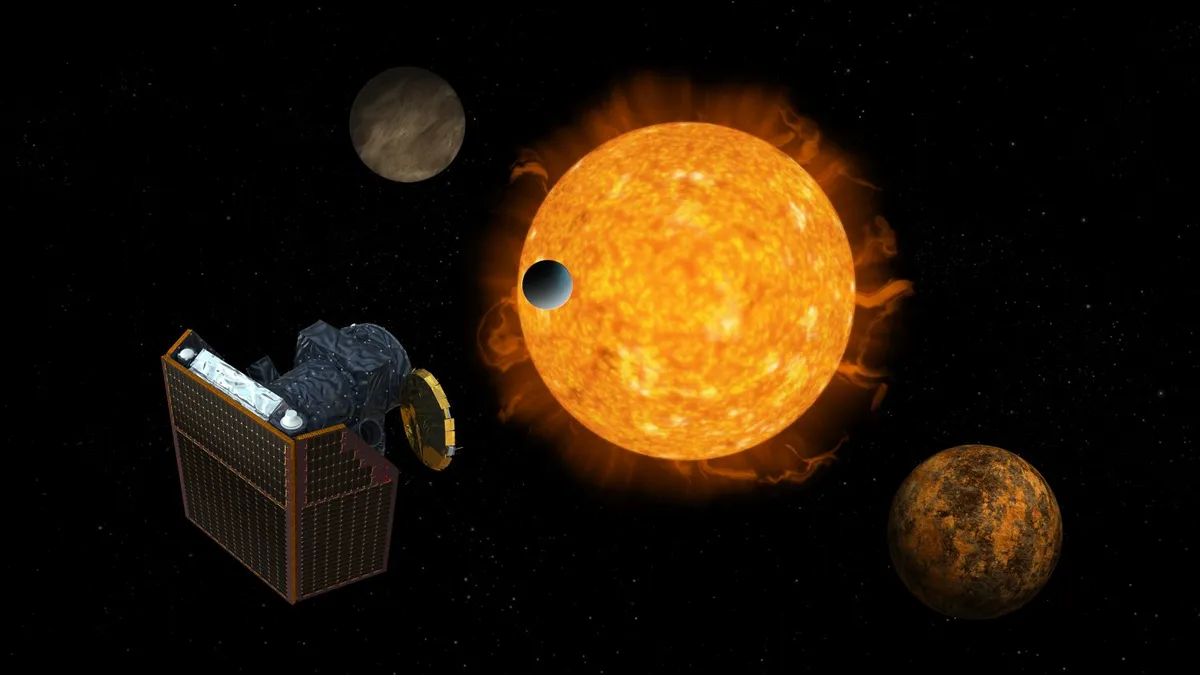

ESA's CHaracterisingExOPlanet Satellite - known as CHEOPS - launched on 17 December 2019 and is the latest spacecraft dedicated to studying planets orbiting stars beyond our Solar System, known as exoplanets.

CHEOPS will not search for exoplanets: instead, it is the first mission that will study bright, nearby stars already known to host exoplanets.

By doing so, the spacecraft will take measurements of each exoplanet's size by observing the body as it passes in front of its host star.

CHEOPS will focus on planets of the super-Earth variety, taking the first steps towards understanding more about these distant worlds.

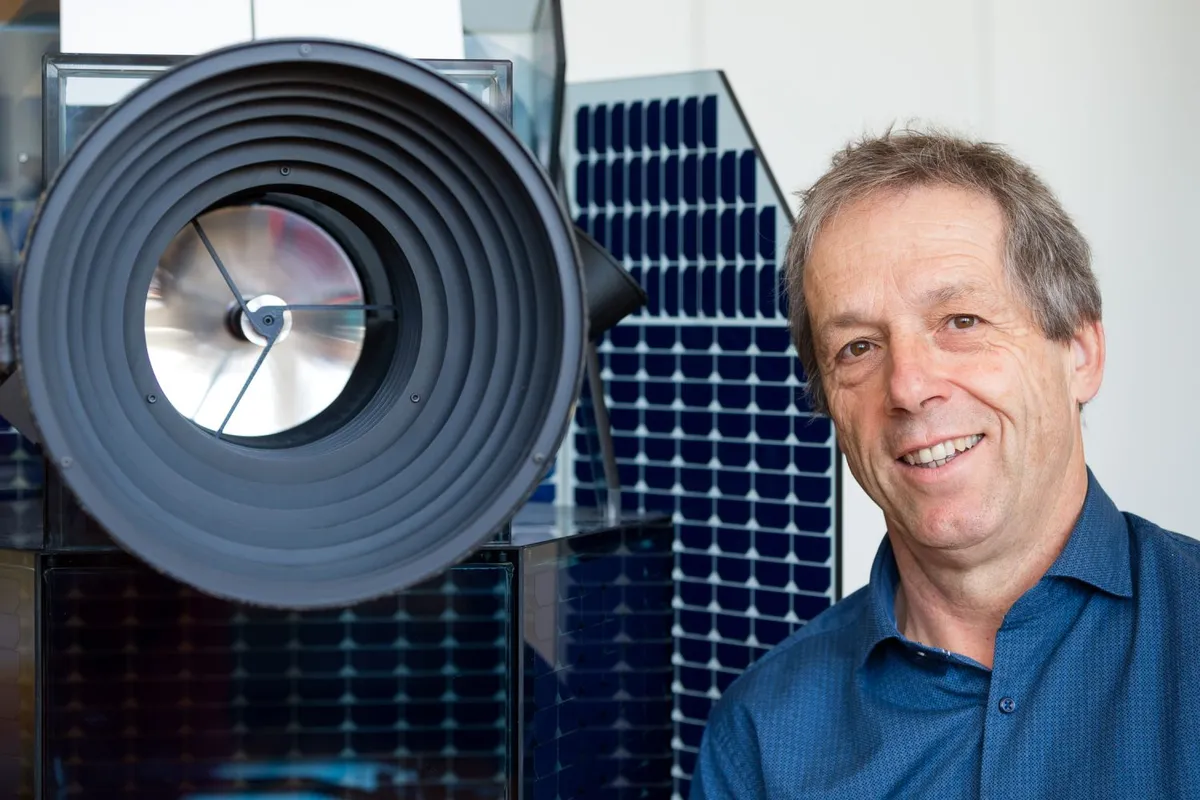

We spoke to Professor Willy Benz, principal investigator of CHEOPS and professor of astrophysics at the University of Bern, to find out more about what the mission will entail.

What is the main goal of the CHEOPS mission?

CHEOPS is the first small science mission from the European Space Agency (ESA) and its goal is to address some outstanding issues in exoplanet science.

The mission aims to do ultra-precise photometry of stars already known to hold planets, to measure the size of the planets.

How will CHEOPS measure exoplanets?

With photometry we look at a star and monitor the light we receive over time. If an exoplanet passes in front, this will dim the light slightly, and that dimming is proportional to the exoplanet’s size.

The bigger the planet, the more the light will be dimmed. This is a technique that has been used by other satellites such as Kepler and TESS, and ESA is due to launch PLATO (PLAnetary Transits and Oscillations of stars) in a few years.

CHEOPS is one element of a discovery chain to look for exoplanets, their properties and characteristics, and eventually down the line – for life.

What makes CHEOPS very different from other missions so far applying this technique is that we are not looking for new planets.

We are a follow-up mission: we look at bright stars which we know have a planet. We are trying to measure this dimming of the light more precisely and get a better measure of the planet’s radius.

How can CHEOPS help our understanding of exoplanets?

We want to know more about exoplanets than simply that they exist: 25 years ago this was pure speculation – we knew only the eight planets of our Solar System.

Now we know that planets may outnumber stars in the Universe. We want to know more.

How big are they? What are they made of? How hot are they? Do they have an atmosphere?

But you have to do a number of measurements. If you have the planet’s size and its mass, you can start computing its density, then you know whether it's rocky or gaseous. You can start understanding its physical nature.

What have been the main challenges of the mission so far?

We must be able to measure the intensity of light to a high precision. This has been a challenge because of satellites in low Earth orbit generating sources of stray light that may affect the precision.

We developed something that should measure light to 20 parts per million (ppm).

When we tried to check this in the lab we realised that there is no light source on Earth sufficiently precise or stable that we could measure.

We actually developed a super-stable light source to check whether our precision is good enough. You can’t buy this off the shelf anywhere.

What's the plan for the mission?

The spacecraft's nominal lifetime is 3.5 years – but secretly we hope for 5.

Over the past 4 years we have prepared a science programme and built a list of a few hundred targets.

But CHEOPS is also an open observatory – 20 per cent of its time will be “open time” to anyone in the community. Anyone with a good idea can submit a proposal to ESA.

How might CHEOPS help find life?

CHEOPS is not going to find life. CHEOPS is an important element to measure exoplanets, and maybe some of the planets we will target later on for bigger facilities – like NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, or the ground-based Extremely Large Telescope – to look at.

CHEOPS is one element of a discovery chain to look for exoplanets, their properties and characteristics, and eventually down the line – for life.

This article originally appeared in the December 2019 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.