On 25 May 1961, US President John Kennedy stood before a joint session of Congress for one of the most farsighted speeches of all time. He would announce America's intentions to land human beings on the Moon and bring them back safely.

But why did Kennedy decide to send US astronauts to the surface of the Moon, and how did they begin preparations for the Apollo missions to clinch victory in the Space Race?

Listen to Kennedy's 25 May 1961 Moon Shot speech in full via the window below, courtesy of www.jfklibrary.org.

Read our interview with filmmaker Rory Kennedy on her uncle's legacy.

Why did Kennedy want to send astronauts to the Moon?

Six weeks before Kennedy's famous Moon Shot speech, Soviet Union cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin had become the first human in space, and the US responded by sending Mercury 7 astronaut Alan Shepard on a short suborbital flight to become the first American in space.

But since his election, Kennedy had been fearful of a broad ‘gap’ in missile-building technology and knew the United States needed to pull ahead of its communist foe, the Soviet Union, who were being led by their rocket man Sergei Korolev.

Now, America's youngest ever head of state - only 4 months into a tenure that would end with his assassination - had a bold trump card to play.

"I believe that this nation should commit itself," Kennedy said in measured tones, "to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth.

"No single space project in this period would be more impressive to mankind or more important for the long-range exploration of space and none would be so difficult or expensive to accomplish."

Kennedy’s words were greeted by rapturous applause. Behind him, Vice President Lyndon Johnson could be seen whispering into the ear of House Speaker Sam Rayburn.

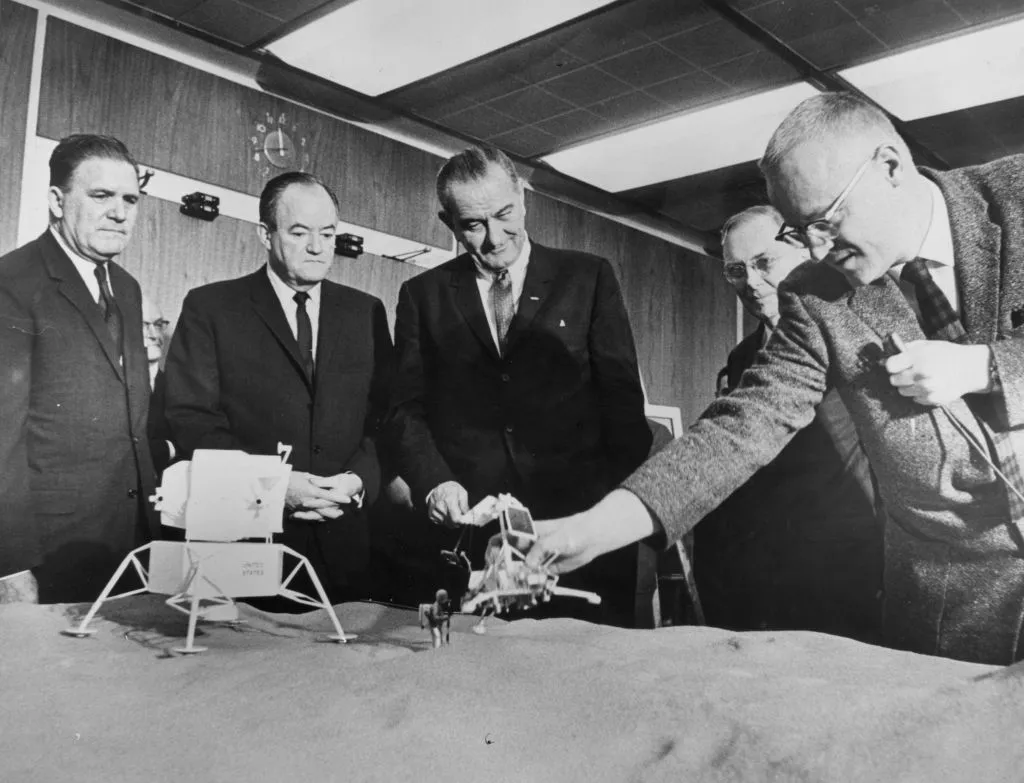

And it was Johnson (as the president’s unexpected successor in the White House) who would push this audacious plan to the cusp of fruition.

America’s future in space, Kennedy explained, had been "under review" since the start of his administration the previous January and never before had a president "marshalled the national resources" for such an immense policy decision. But now was the time to take longer strides.

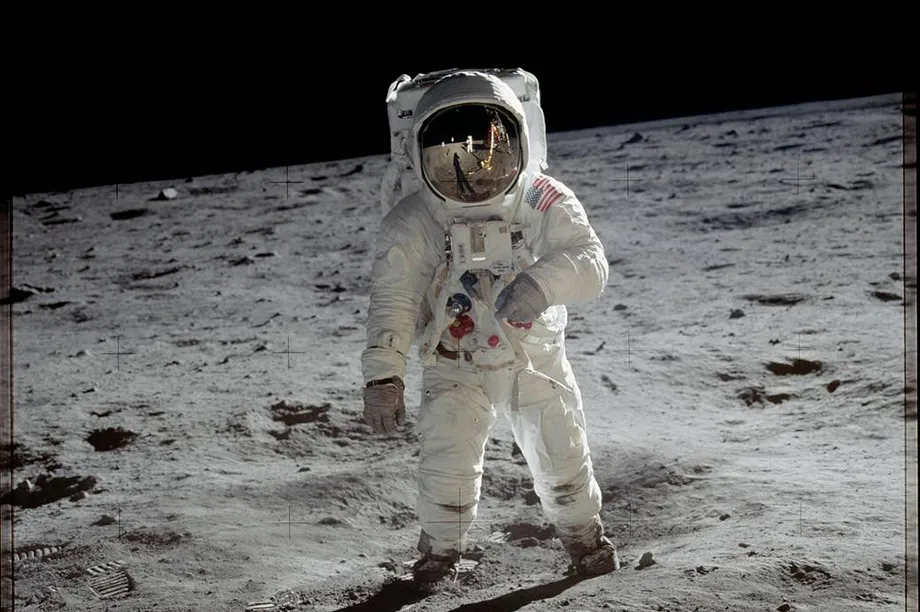

Six decades on, as every school-age child knows, those strides and that goal were triumphantly met within that tight timeline with the success of the Apollo 11 mission, but the background to Kennedy’s 'Moon Speech' was complex, as were his motives.

How the US space programme began

The idea was not a new one. Early in 1959, NASA Administrator Keith Glennan told Congress there was "a good chance that within ten years" a manned circumnavigation of Earth’s closest celestial neighbour would be accomplished.

And although President Dwight Eisenhower approved the accelerated development of the giant Saturn V rocket to get there, his keenness to balance America’s budgetary books "come hell or high water" did not sit well with the enormity of its projected $15 billion cost.

Glennan knew any formal commitment would have to await the next president.

But in February 1961, soon after Kennedy’s inauguration, NASA published a report that considered a manned lunar landing to be possible by 1968-1970.

The new president installed MIT professor Jerome Wiesner as his science advisor and proved highly supportive of the space agency, boosting its budget by $125 million over the $1.1 billion appropriations cap during his early weeks in office.

Then, as they often do, terrestrial matters got in on the act.

In April, the triumphant flight of Gagarin and the failure a few days later by CIA-backed Cuban exiles to topple Fidel Castro at the Bay of Pigs caused huge international embarrassment.

NASA’s leaders were verbally roasted by the House Space Committee, whilst Kennedy’s unproven administration was left humiliated and red-faced.

Informal brainstorming sessions brought landing a human being on the Moon back to the fore, as a means of gaining credibility for a beleaguered government.

Kennedy’s first point of contact was Johnson, whose remit included chairmanship of the National Aeronautics and Space Council.

"Is there any space programme that promises dramatic results in which we could win?" he asked Johnson.

"Do we have a chance of beating the Soviets by putting a laboratory in space or by a trip around the Moon or by a rocket to land on the Moon or by a rocket to go to the Moon and back with a man?"

Later in April, the famed rocket engineer Wernher von Braun felt the "sporting chance" of sending astronauts around the Moon before the Soviets was markedly brighter than launching a laboratory into space.

Both nations would need to create a booster with a performance jump of a factor of ten over the capabilities of their current arsenal to reach the Moon.

"Whilst today we do not have such a rocket," cautioned von Braun, "it is unlikely that the Soviets have it."

An all-out crash effort, he concluded, could see an American astronaut standing on the Moon by 1967. That judgement won the day for Johnson.

And following Shepard’s flight in early May, Kennedy was won over too. But the same could not be said of the nation, with early Gallup polls indicating only 42% of Americans supported the push for the Moon.

The president acknowledged the "staggering sums" involved, remarking that Americans spent more per week on cigarettes and tobacco.

He also had to fend off criticism for underfunding social welfare and educational projects. Reaching the Moon, Wiesner said later, was a decision he made "cold-bloodedly".

Yet as his presidency wore on, advisors speculated that Kennedy became increasingly alarmed by the programme’s burgeoning costs.

In a November 1962 meeting with NASA Administrator Jim Webb, he categorically remarked that he was "not that interested in space" and his position was purely one of beating the Soviet Union.

Others saw him differently. "He was really a space cadet," said Alan Shepard, America’s first astronaut. "And it’s too bad he could not have lived to see his promise."

Ben Evans is the author of several books on human spaceflight and is a science and astronomy writer.