The Mercury 7 were a group of astronauts selected by NASA to undertake crewed missions as part of Project Mercury, which would help boost the American space programme and prove that human spaceflight was a possibility.

The progress made and lessons during Project Mercury would ultimately lead to the development of the Apollo programme to put human feet on the surface of the Moon.

The Mercury 7 astronauts were:

- Scott Carpenter

- L. Gordon Cooper, Jr.

- John H. Glenn, Jr.

- Virgil I. "Gus" Grissom

- Walter M. Schirra, Jr.

- Alan B. Shepard, Jr.

- Donald K. "Deke" Slayton

What was NASA's Project Mercury?

NASA announced Project Mercury on 7 October 1958 as a new programme that would set in motion a boom in human spaceflight for the USA.

The project's goals were to put a crewed spacecraft into orbit around Earth, observe and collect data on the mission, and then return the human crew to Earth safely.

At this point, very little was known about human spaceflight. Could a NASA astronaut be launched into orbit, manoeuvre and control the spacecraft in a weightless environment, and then successfully land back on Earth?

There was only one way to find out.

6 spaceflights were made during Project Mercury: 2 suborbital flights that saw the astronauts launch into space and return to Earth, and 4 missions that orbited Earth before returning.

Why were they called the Mercury 7?

The spaceflight project was called 'Mercury', named after a Roman god who was known for his speediness.

All of the astronauts in the Mercury programme named their own spacecraft.

Alan Shepard, the first American in space, flew in a capsule called 'Freedom 7' because it was the 7th capsule made for the project.

The other Mercury astronauts used the number 7 in the name of their capsules in honour of the number of astronauts selected for the programme.

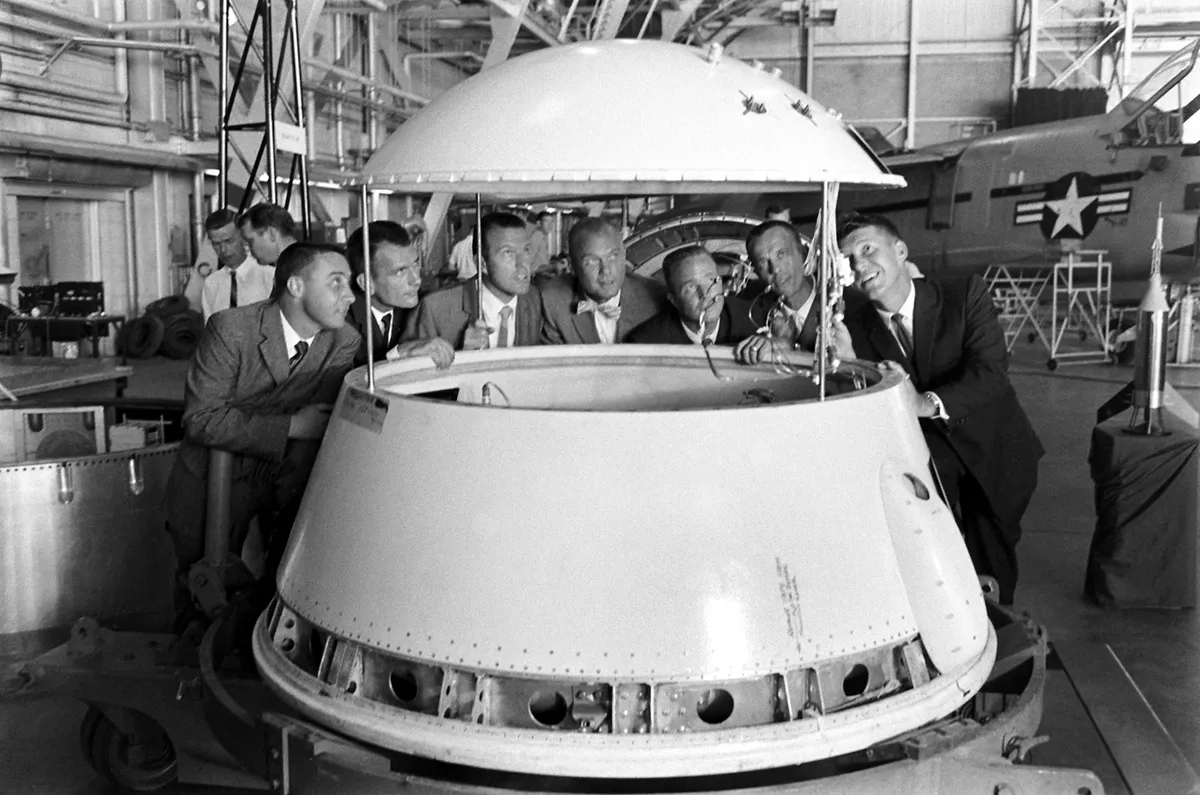

Selecting the Mercury 7 astronauts

It must have seemed obvious to the NASA selection committee that the most well-suited candidates for missions such as these would be pilots: specifically military test pilots.

In January 1959, 508 service records of a group of test pilots were examined, and 110 candidates were selected from that group.

In a matter of weeks, that group had been reduced to 32 candidates, 18 of which were recommended for Project Mercury.

The Mercury 7 were America's first astronauts and laid the groundwork for the Apollo 11 mission that, a decade later, would successfully land human beings on the Moon for the first time in history.

All of the Mercury 7 astronauts flew into space except Deke Slayton, who was deemed unfit to fly due to a previously-undetected heart condition.

However, Slayton would later fly in the Apollo-Soyuz mission in 1975, which saw the USA and USSR collaborate on a space mission for the first time.

During the mission, the US Apollo module docked with a Soviet Union Soyuz spacecraft.

Project Mercury lasted 5 years and saw a total of 6 crewed flights and 8 automated flights.

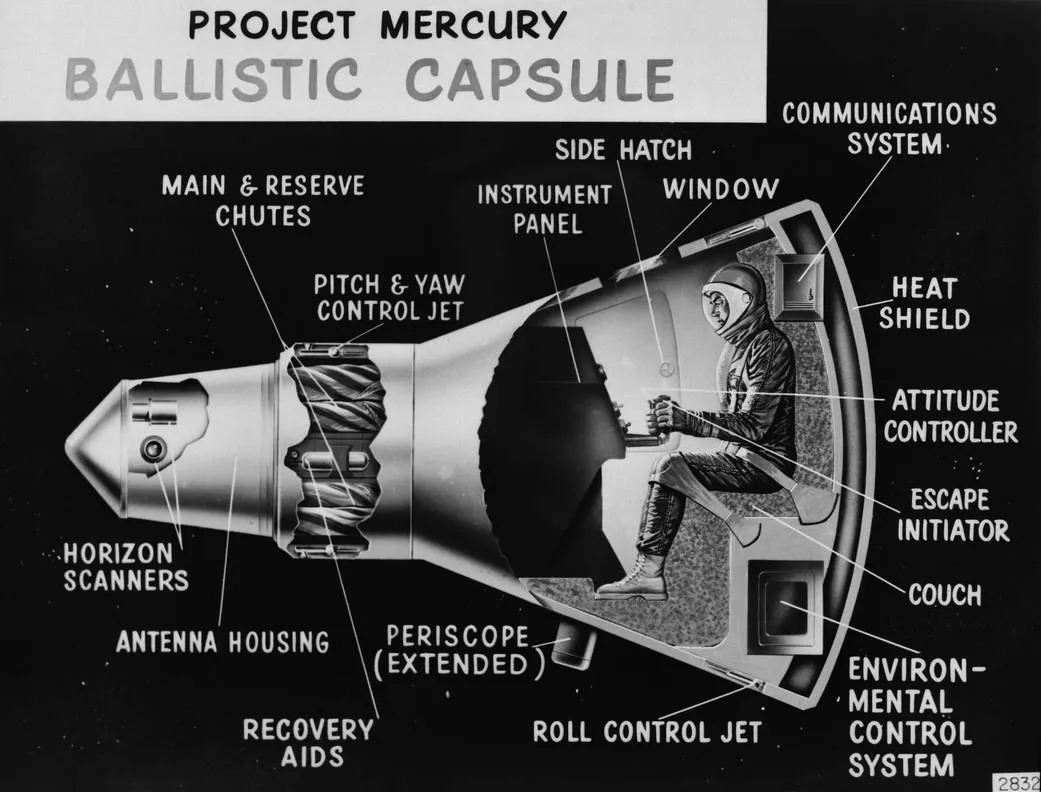

The Project Mercury capsule

At 3.5m long and having a volume of just 1.7m3, it was said that you wore the Mercury capsule rather than flew in it.

With a fuelled mass of 1,355kg, it weighed less than a third of Yuri Gagarin’s Vostok craft.

For test pilots used to controlling every aspect of a flight, there was precious little for them to do, except to control attitude (orientation) with thrusters.

As a result, air force pilots like the legendary Chuck Yeager dubbed the astronauts “spam in a can”.

The Mercury 7 astronauts did, however, lobby successfully for a larger window and manual re-entry controls.

An internal thermal control system regulated the temperature inside the capsule, while its titanium outer casing was protected for re-entry by a fibreglass resin heatshield.

Who were the Mercury 7 astronauts?

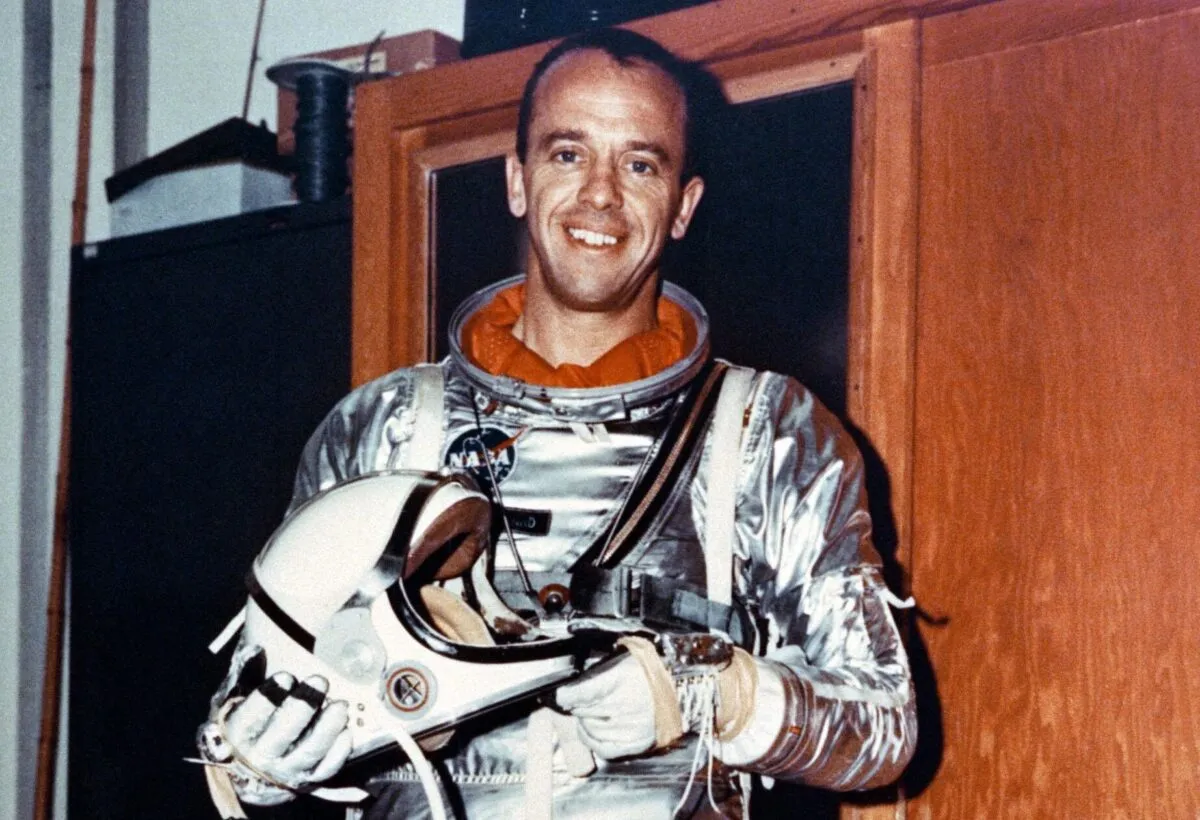

Alan Shepard

America’s first man in space was Alan Shepard, a Navy test pilot who had also served in the Pacific during World War II.

With more than 8,000 hours flying time in his naval career, he was chosen for NASA’s first mission into space.

Originally planned for 1960, the Mercury-Redstone 3 mission was delayed by technical problems, and Shepard could only look on as Yuri Gagarin went down in history as the first man in space ahead of him.

But 45 million Americans were at least able to celebrate Shepard become their first countryman to achieve that feat, on 5 May 1961, piloting the delayed mission aboard Freedom 7.

The flight lasted barely 15 minutes but Shepard had made history. When asked what had gone through his mind as he waited for lift-off, Shepard replied: “The fact that every part of the ship was built by the low bidder.”

He made his second spaceflight in 1971 as commander of Apollo 14, famously hitting golf balls on the Moon, before retiring in 1974. He died in 1998.

Virgil ‘Gus’ Grissom

The second American in space, Virgil ‘Gus’ Grissom was born in 1926 and joined the newly established United States Air Force in 1950, after attaining a mechanical engineering degree.

He served in Korea, where he was cited for 'superlative airmanship' and, having made Air Force Captain by 1959, was assigned to Project Mercury the same year.

In 1961 he piloted Liberty Bell 7 (Mercury-Redstone 4), NASA’s second sub-orbital spaceflight.

The flight itself went well but Grissom nearly drowned on splashdown when the hatch release suddenly activated, flooding the capsule and sinking it moments after he escaped.

"I was scared a good portion of the time," Grissom admitted. It was perhaps a warning of things to come.

His next mission in 1965 (the first of the Gemini programme) was successful, but tragedy struck in 1967 when Grissom and his crew were killed in a fire aboard Apollo 1 during a pre-launch test.

It was set to be the first manned flight of the Apollo programme.

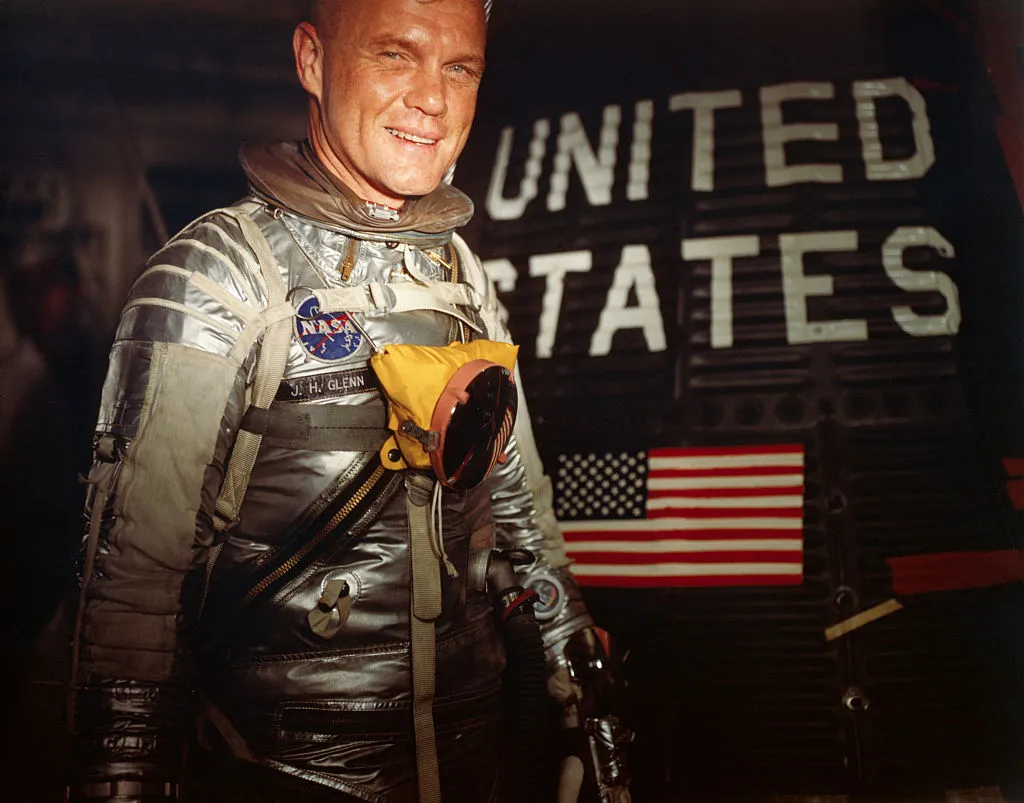

John Glenn

Born in 1921, John Glenn was the fifth man in space and the first American to orbit the Earth.

He dropped out of college in 1941 to join up after the attack on Pearl Harbor, flying 59 combat missions as a Marine pilot in the South Pacific, then doing two tours of duty in the Korean War before becoming a Navy test pilot.

In 1957, he completed the first supersonic transcontinental flight, from Los Alamitos, California to New York.

Despite not having the requisite college degree, he was selected for Project Mercury in recognition of his achievements as a pilot. America held its breath as Glenn blasted off on Mercury’s Friendship 7 (Mercury-Atlas 6) on 20 February 1962, becoming the country’s first citizen to orbit the Earth.

Glenn was forced to take manual control after the autopilot failed on two of the three orbits, and feared for his life when a heat shield appeared to be loose during re-entry.

Such calmness under pressure made him something of a national hero and he became a senator in 1974, serving for 25 years.

In 1998, aged 77, he became the oldest man in space, flying aboard Space Shuttle Discovery. John Glenn died in 2016 at the age of 95.

Malcolm Scott Carpenter

As the first American to eat solid food in space, Scott Carpenter can perhaps claim a more obscure achievement than his Project Mercury colleagues.

Born in 1925, Carpenter trained as a Navy pilot during World War II. He served in Korea, then became a Navy test pilot in 1954.

Five years later he was recruited as back-up for John Glenn. When fellow astronaut Donald ‘Deke’ Slayton withdrew for medical reasons from Aurora 7 (the mission following Glenn’s), Carpenter replaced him.

On 24 May 1962 he achieved his dream and blasted off for a five-hour mission on Mercury-Atlas 7. However, on return to Earth a system malfunction pulled the craft to the right, causing it to overshoot the re-entry point.

There were anxious moments as Carpenter manually corrected the re-entry angle, but despite an overshoot of 400km, he splashed down safely.

An injury sustained in a motorbike accident in 1964 ended hopes of further flights, so the astronaut turned aquanaut the following year, spending 30 days on the ocean floor as part of the Navy’s Sealab project.

Retiring from the Navy in 1969, he set up Sea Sciences Inc to develop the ocean’s resources.

Walter ‘Wally’ Schirra

Born into an aviation family in 1923 (his father was a stunt pilot for his wing-walking mother!), Schirra inherited their flying skills and sense of fun.

Graduating in aeronautical engineering in 1944, he served in Korea before becoming a Navy test pilot.

He joined Mercury in the specialist area of life support systems, and on 3 October 1962 piloted Sigma 7 (Mercury-Atlas 8) on a nine-hour mission to evaluate systems and equipment.

NASA’s longest mission at the time paved the way for Mercury-Atlas 9’s full-day flight – the original aim of Project Mercury – the following year.

On his return to Earth, Schirra found his achievement eclipsed by the Cuban Missile Crisis. But he would go on to enjoy two further missions – one with Gemini 6 in 1965 and another commanding Apollo 7 in 1968 – becoming the first person to go into space three times.

His humour was evident in both: he played Jingle Bells on harmonica during Gemini 6A and became a spokesman for Actifed after catching a cold aboard Apollo 7.

With Walter Cronkite he commentated on the 1969 Moon landing for TV. He died in 2007 and has a Naval cargo ship, the USNS Wally Schirra, named in his honour.

L Gordon Cooper

The first man to make two Earth orbits, Cooper was born in 1927 and counted treasure-hunting and archaeology among his interests, as well as aviation.

He joined the Army after graduating in aeronautical engineering but transferred to the Air Force as a test pilot.

A colonel by the time Project Mercury recruited him in April 1959, he piloted the final Mercury mission, Faith 7 (Mercury-Atlas 9) on 15 May 1963, to see if a manned craft could remain in space for an entire day.

Some 34 hours and 22 Earth orbits later, Cooper had proved it could, but not without some difficulties: an electrical fault on the penultimate orbit left his control system without power, and there were high levels of CO2 in the cockpit – a problem that would return to haunt Apollo 13.

"Things are beginning to stack up a little," remarked Cooper to mission control, before calmly firing the retro rockets manually for a successful re-entry.

Project Mercury had fulfilled its purpose, but Cooper established a new endurance record just two years later with Mercury’s successor, commanding Gemini 5 in an eight-day, 120-Earth orbit mission, and flying a record 5,331,745km in the process.

By the time he retired in 1970 (after serving as back-up commander for both Gemini 12 and Apollo 10), Cooper had clocked up 222 hours in space. He died in 2004 at the age of 77.

Donald ‘Deke’ Slayton

Born in 1924, Slayton was the Mercury astronaut who never was. Joining the programme after serving as a bomber pilot, then an instructor, in World War II, a heart condition robbed him of the chance to pilot Aurora 7, with Malcolm Scott Carpenter replacing him.

Instead, he served the Mercury, Gemini and Apollo missions in senior but ground-based roles.

Slayton was determined to regain his flight status, exercising daily, quitting smoking and cutting down on alcohol.

It worked – he regained his flight status in 1972, and finally realised his ambition as the docking pilot for the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project in 1975.

It was the first meeting in space between the Americans and Soviets, as an Apollo craft docked successfully with Soyuz 19 for 44 hours.

Slayton’s sole flight lasted 217 hours, 28 minutes and 24 seconds. From 1977 until his retirement in 1982, Slayton served as NASA’s Manager for Orbital Flight Test. He died of cancer in 1993.