Few people know the International Space Staton better than US astronaut Jeff Williams.

Having been selected for the NASA Astronaut Class of 1996, throughout his career as an astronaut Williams flew into space four times: first on the Space Shuttle during mission STS-101 and three subsequent trips to the ISS on the Russian Soyuz rocket.

Williams was part of the large team of astronauts that constructed the International Space Station, and during his time as a resident of the orbiting laboratory the NASA astronaut took part in numerous scientific experiments as well as missions to install some its most integral components, such as the Tranquility Module and the Cupola.

With 534 accumulative days under his belt, Williams holds the record for the most time spent on the ISS by a male NASA astronaut.

Read more about the ISS:

- How to see the International Space Station in the night sky

- Interview with ESA astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti

- What are the biggest dangers on the International Space Station?

As we approach the 20th anniversary of the first occupation of the International Space Station in November 2020, we got the chance to speak to Williams to find out what it was like being involved in the construction of the ISS, how its collaborative nature has changed spaceflight forever, and what the future may hold as humanity ventures beyond low Earth orbit.

You can also listen to our interview with Jeff Williams on the Radio Astronomy podcast below.

What were the challenges of building the International Space Station, and what challenges do you think lie ahead?

The story of the International Space Station is a story largely unknown and too little told. One of the reasons it's largely not well known to the general public, I think, is because it occurred over a very long period of time.

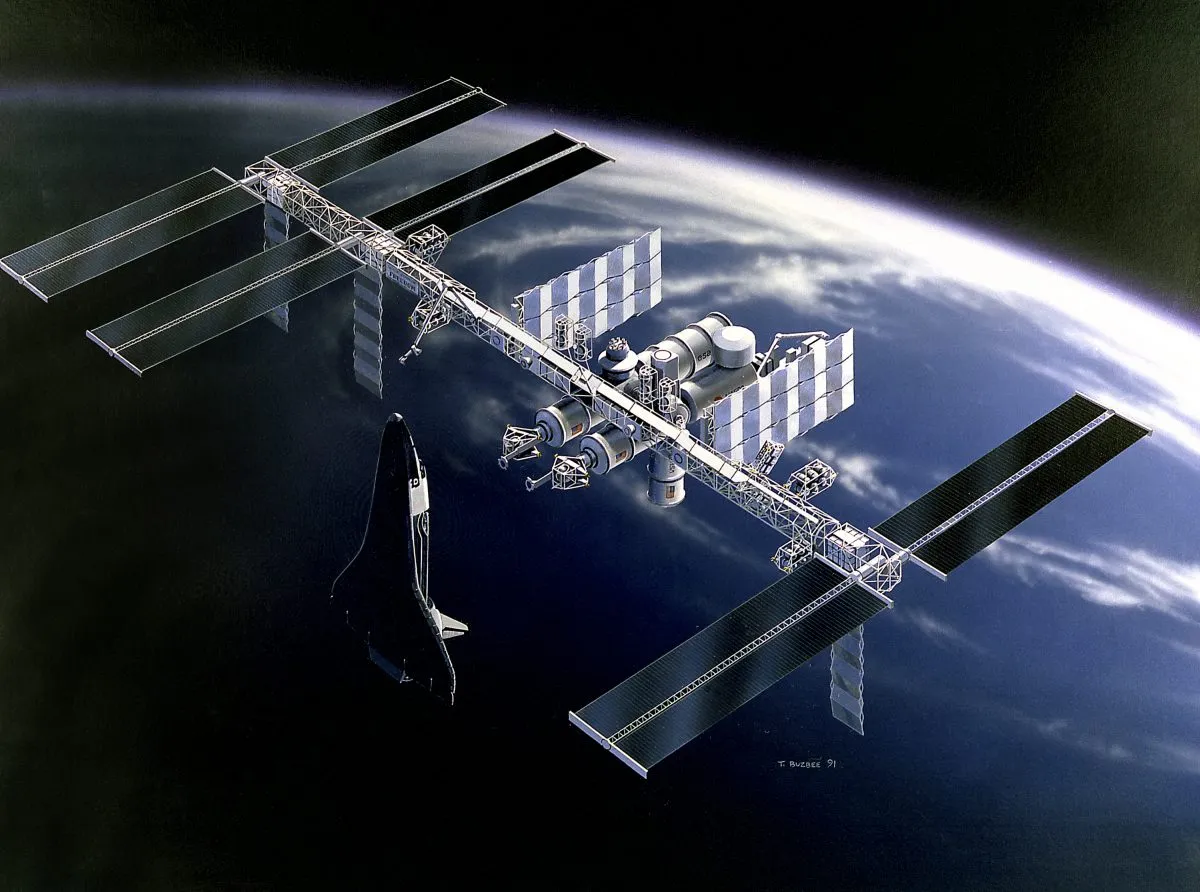

I started working on it in the mid 1990s but, of course, its beginnings go even further back than that. It goes all the way back to the 1980s with Space Station Freedom and, parallel to that, the Russians were working on their Mir space station and planning a Mir 2 when the Soviet Union fell.

Some smart folks got together both on our side and the Russian side in 1992, 1993 and formulated this proposal to put Mir 2 and Freedom together.

Both were in jeopardy to ever fly because they didn't have the support that they needed to get off the ground.

But combining the two entities at the fall of the Soviet Union provided the circumstances for the political support to come together and be sustained enough to actually build it.

I joined the Space Station program as an astronaut in 1996 and we were beginning our involvement with Russia in those years by flying Americans on the Mir space station, and that that set the groundwork for the ability of the two space agencies to operate together.

Our system and their system, of course, are very different, and it took a while to integrate the operations. That was foundational in terms of then later beginning to build the ISS, the first element of which launched in 1998.

We all consider this program significant in that we are working as an international cooperative effort. The partnership is stronger than it's ever been

It was not an easy road to get there. Not only the political support, but the technical integration of all the components that needed to go together in every part of this space station was dependent upon the success of the steps that were going to go before each of those parts.

When you step back and look at the whole assembly, it was I think 37 Space Shuttle flights dedicated to building the Space Station.

Most of those flights took up a major component of the Space Station. Some of them were logistics missions that supplied the station.

There were also about roughly 40 Russian Soyuz rocket launches that supported the assembly of the ISS as well.

My first visit there was in the spring of 2000. It was the third Space Shuttle flight to visit the Space Station, which at that time was only made up of two modules: one Russian built module and an American built module.

It was before Expedition 1 got there, so we were still in the very early phases before its permanent occupancy, and certain elements were already presenting significant challenges to us.

There were subsequent modules that were being delayed in their development. There were some technical issues that were slowing things down. There were financial issues on both sides, budget issues.

My mission launched in May of 2000 to fix some components that were failing on the station, to keep it alive. Thankfully after our mission there was a critical launch of a Russian component: the service module that enabled the pathway to launch Expedition 1 in the fall of 2000.

And now we're approaching 20 years of continuous human exploration in space, which is a significant milestone, largely unknown to the general public.

There were many challenges along the way. There were technical issues that we had to work through. There were political issues and budgetary issues that we had to work through.

There was, of course, the tragedy of the loss of the Columbia crew. Three of those crew members were my classmates. All of them were my friends. And that's not just me: they were they were friends and coworkers of many people here, specifically at Johnson Space Center.

But they were well known in the wider community as well, so that was a very personal loss and tragedy that we had to work through.

Looking back, it's a great testimony to the strength of the partnership, particularly between the US and Russia, just to keep the Space Station going and keep it alive while we addressed the issues that caused the Columbia tragedy, which of course grounded the Space Shuttle for between two and three years.

At that time, we started rotating all of the crews to and from the Space Station on a Russian Soyuz rocket and it's been that way predominantly ever since.

The Space Shuttle, when it started flying again, was used to continue the assembly, not to rotate the expeditionary crews. My second visit to the Space Station was during the time the Shuttle was grounded in 2006.

That became the first of three times that I personally rode on the Soyuz. During that mission Pavel Vinogradov and I, we were the last two-person crew during that period of time while we recovered from the Columbia accident and returned to the Space Shuttle to flight status.

It's important to maintain a lower orbit presence. It will be necessary to successfully develop an infrastructure at and around the Moon.

In fact, halfway during our 6-month stay we successfully returned the Space Shuttle to flight with the launch of Discovery and STS-121, and they brought supplies and equipment that we needed.

But they also brought Tomas Reiter from Germany and he joined our Expedition 13 to round out the crew of three at the time. That was a significant milestone because that was the first time that we had an expeditionary crew member not only from Russia and the US, but from the European Space Agency as well.

Your own Tim Peake from the UK actually flew with me. I overlapped him on my last visit up there in 2016, but that Thomas Reiter was the first partner astronaut from the balance of the partnership made up of the European Space Agency, Japan and Canada.

The International Space Station seems to represent the harmonising effect space can have on nations. Can this collaborative culture can continue without the ISS?

Well, I've been in orbit with 57 different individuals. Many of those were from our partner agencies Russia, Europe, Japan and Canada.

Within the astronaut cosmonaut corps we all collectively consider this program to be very significant in that we are working as an international cooperative effort.

We work very well together. The partnership is stronger now than it's ever been, and that includes our Russian partners.

And in spite of the political and diplomatic issues that have been going on for now quite a few years, we largely operate below the radar of the issues that go on in the media and the daily news cycles.

For the most part, the different countries involved leave us alone and allow us to do our work.

History shows that whenever you have issues between countries, if there is engagement largely below the radar, below the daily public visibility, that engagement has a positive impact in the long term to allow countries and nations to reconcile or to avoid escalation, and I trust that the ISS has been doing that, particularly between the US and Russia.

How do you think we can balance enabling an economy with the International Space Station while still making sure that we remember this collaborative culture that has been enshrined the last 20 years?

That's a great point because especially in recent years with the advance of technologies and the potential for sinister use of those technologies, that has become more and more at the forefront of how we do business.

We protect data more than we did say 15, 20 years ago because of the threats out there. And then we have commercial entities that have entered onto the stage and, of course, they have proprietary interests that that they want to protect, rightfully so.

So we're growing and we're learning how to be collaborative, how to join in partnership and combine capabilities, but at the same time honour the necessity to protect proprietary data and national security interests as well.

We've recently seen the successful use of the Space X Dragon. What do you make of this new emerging spacecraft and space technology?

It's obviously a big new development in recent years that not only Space X, but other companies have entered the stage, if you will, of human space exploration, trying to develop technologies.

Thinking specifically about the Space X test flight, we were very pleased with the success that we enjoyed.

Obviously, it's still very early in its development.There will be plenty of work to go not only on that vehicle, but other new vehicles as well that are also in the pipeline.

But it's all good. It builds redundancy. It broadens the spectrum of participants and it broadens the potential for its use in the future.

Studying the human body is going to be one of the more significant benefits from the ISS. We need to develop those countermeasures before we send crews to the Moon and Mars.

It develops tools and resources that can be applied in different ways that will go beyond the Space Station.

Consider the landing of the rocket boosters. Of course that's a new development that has lots of potential to build on the economics and the business model of being able to support launch services.

In this case you don't have to rebuild a rocket for every launch, so all of this is very good. It reminds me of the early days of aviation: a lot of short hauls, not well integrated, not that many flights and not that many customers, relatively expensive at the time.

But now we see where we are today. And the world is very dependent upon that in terms of the normal economics and commerce of the world, and people moving around all the time.

There's talk of enabling a low Earth orbit economy, privatising the operations of the Space Station. There are also debates around reusing its components for future space stations. What you think should happen to the International Space Station next?

I think all of those things that you mentioned are important to look at and to try to develop. Some aspects will probably come to fruition because they make sense and things fit.

You have the right parties interested in coming on the stage. Some aspects may not work, but a lot of this is trial and error and it’s dependent upon the continued success of the operation.

We have a hard time seeing what the future holds because we're largely lost in the trees, and we’ll only see the forest in hindsight. That's just the way it is.

But it is important, I think, to maintain a lower orbit presence. I think that will be a combination of both government work as well as commercial work.

That presence will be necessary to successfully develop an infrastructure at and around the Moon and to conduct operations around the Moon.

I think the current policy is also to make that, as much as practical, a combination of government and private enterprise as well.

It just broadens the political support. It broadens the mind, the support in general to accomplish those things.It broadens the array of stakeholders that are interested in completing it, in maintenance, making it successful.

One major benefit of the ISS is the scientific discoveries made onboard. Is there one experiment you did on the ISS that you thought could be a game changer?

It's hard to pick out one. I've been involved in hundreds of them and some of them I can't even remember without looking them up.

There was one that was just kind of fun because we were flying what you might call robots and we programmed them to manoeuvre around inside the Space Station, and they talk to each other. It was called SPHERES.

And there was an experiment that was developing satellite control systems, which was a lot of fun.

The variety of what you can see is endless: studying different places on Earth and lighting conditions and watching seasons go by.

There was another one that just looked at fluid dynamics in the science of capillary flow. That was a lot of fun because it was visually interesting: it's interesting in a weightless environment to work with fluids and different shapes.

We do a lot of ultrasounds of heart and other body organs. We're learning things about how we breathe a little higher level of CO2 concentrations up there just because the equipment doesn't get it down to what we're used to here on the ground, and that has more of an impact on the human body than we previously assumed.

Studying the human body, I think, is going to end up being one of the more significant benefits that come from the ISS because we need to develop those countermeasures before we send crews to the Moon and Mars.

You helped install the Cupola onto the Space Station, which gives astronauts a great view of Earth. How excited were you to be part of that?

Absolutely. I still had about a month and a half, as I recall, maybe a month or so on board, so I used it quite a bit to shoot photography. So that was a big milestone.

It's what I called the window on the world, because it's the only place on the Space Station that you can see the entire globe from a single vantage point.

I grew to appreciate very early on, even back in the ‘90s before my first flight, that I really had to capture the experience. And the best way to do that was through photography.

I had two motivations for that. One was so that I could remember and recall the experience, but probably the bigger motivation was to be able to vicariously bring the experience to people on Earth.

Personally I prefer still photography over video because you can study and look at a photograph forever.

Video goes by and the scene is gone forever, unless you replay it, of course. The variety of what you can see from that vantage point is endless in terms of studying different places on Earth and different lighting conditions and watching seasons go by.

The cupola is the window on the world and it’s a fascinating place. It quickly became everybody's favourite place to hang out during their free time.

Nisha Beerjeraz-Hoyle is a space writer and journalist.

For more info on Jeff Williams visit the Jeffrey N. Williams NASA webpage or follow him on Twitter @Astro_Jeff.