Ingenuity has successfully taken off and re-landed on the surface of Mars.

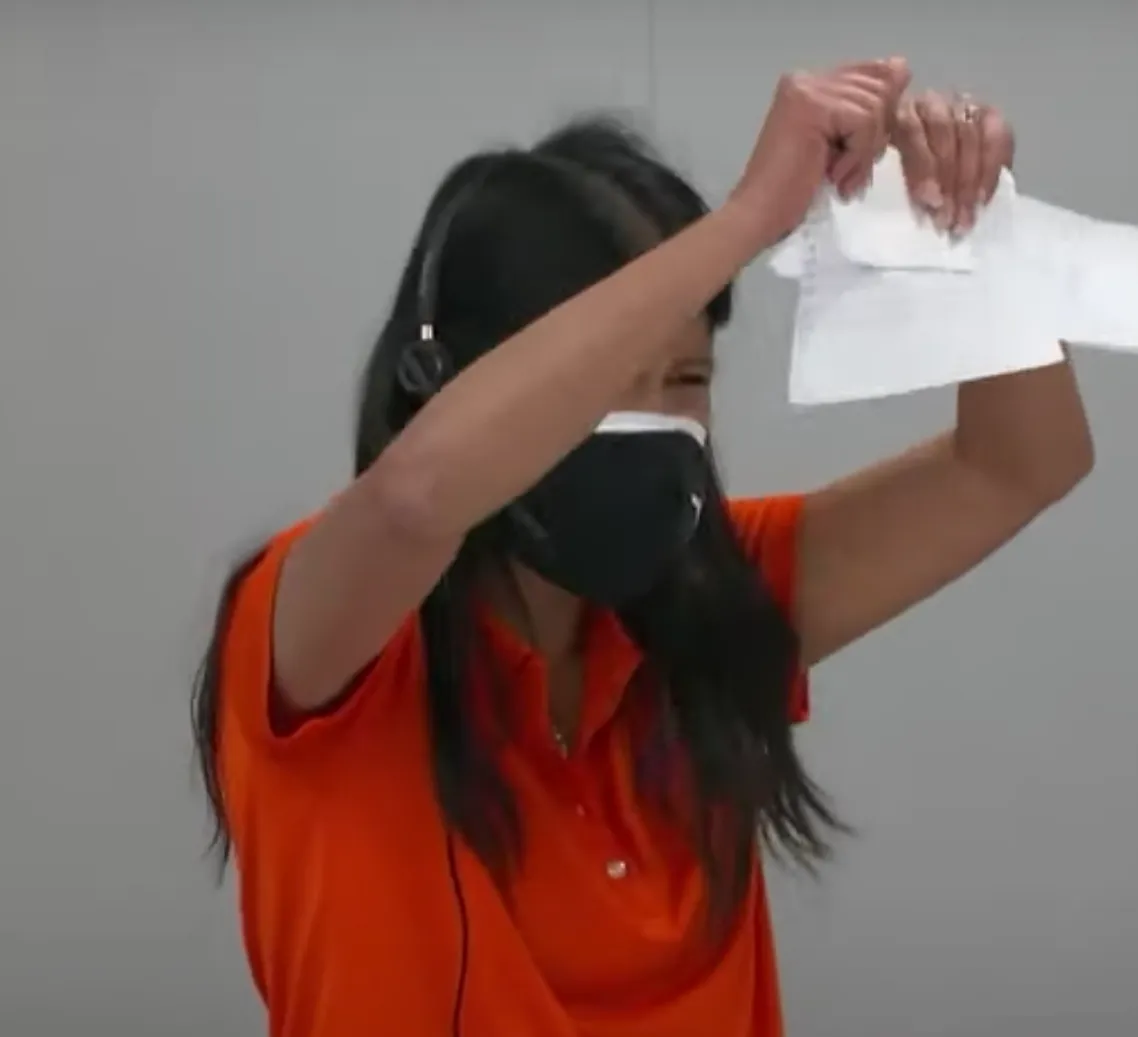

“We can now say that human beings have flown a rotorcraft on another planet,” says MiMi Aung, Ingenuity’s project manager.

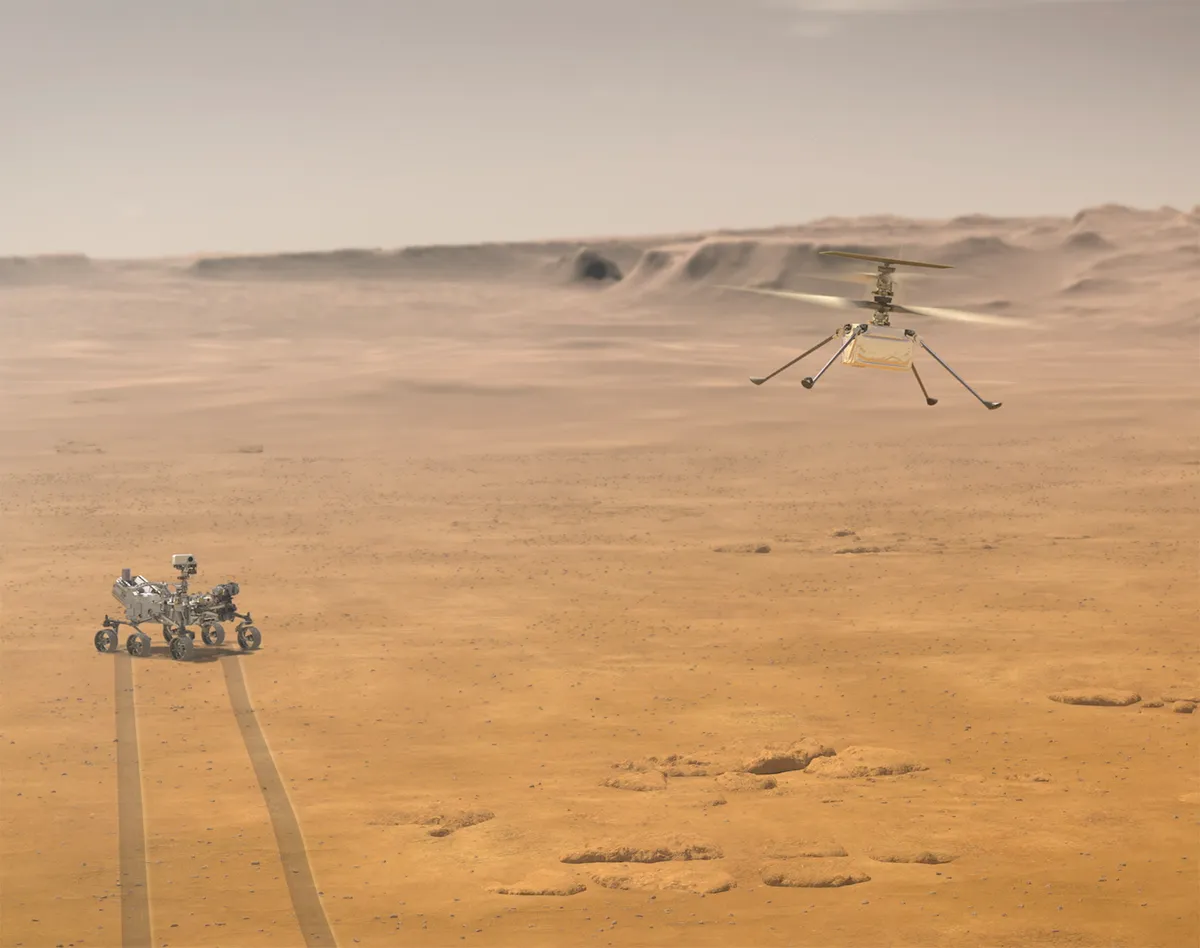

The spacecraft – a drone-like probe which travelled to Mars alongside NASA’s Perseverance rover – rose just over 3m from the planet’s surface, hovered for around 30s before landing.

"First flight is all about being able to demonstrate that we can fly on another planet," says mechanical engineer Taryn Bailey who helped develop Ingenuity, before the flight.

"We’ll do a 3m hover above the Martian surface, touch back down to prove success and then we’ll move on from there."

NASA intend on a total of five flights. The next flight will attempt to move a few meters horizontally away from the launch site, then return. Then flights will travel increasingly far away to test how far the spacecraft can go.

"Whatever the outcome, we are set here to learn," says Aung.

Taking off from Mars is a lot more difficult than taking off from Earth, as the Martian atmosphere is just 1% the pressure of our home planet.

That means its rotors have to spin at around 2000 to 3000 times per minute (on Earth, helicopters only rotate at 400 to 500 rpm). That takes a lot of energy, however the spacecraft must also be light – around 2kg – meaning it can’t have large, heavy batteries to power itself.

For the last six years, the Ingenuity development team have been attempting to balance these conflicting needs to build the first helicopter scout.

NASA were able to simulate Martian conditions in large vacuum chambers here on Earth, which recreated the pressure and temperature of Mars, as well as using a gravitational compensation mechanism to mimic Mars gravity.

“It's important to simulate the Mars like atmosphere in training and in doing so we knew we had the best chance of succeeding on Mars,” says Bailey.

However, the only way to really know if a rotor spacecraft will work on Mars was to take one to the Red Planet and see if it works.

If Ingenuity proves to be successful, the technology will no doubt be deployed in future missions to Mars.

As aerial vehicles can simply fly over surface rocks, rather than navigate around them, it's hoped that future missions will be able to reach areas too dangerous for rovers to explore and give us an entirely new view of the Martian surface.