The long-awaited James Webb Space Telescope is ushering in a new era of space observation.

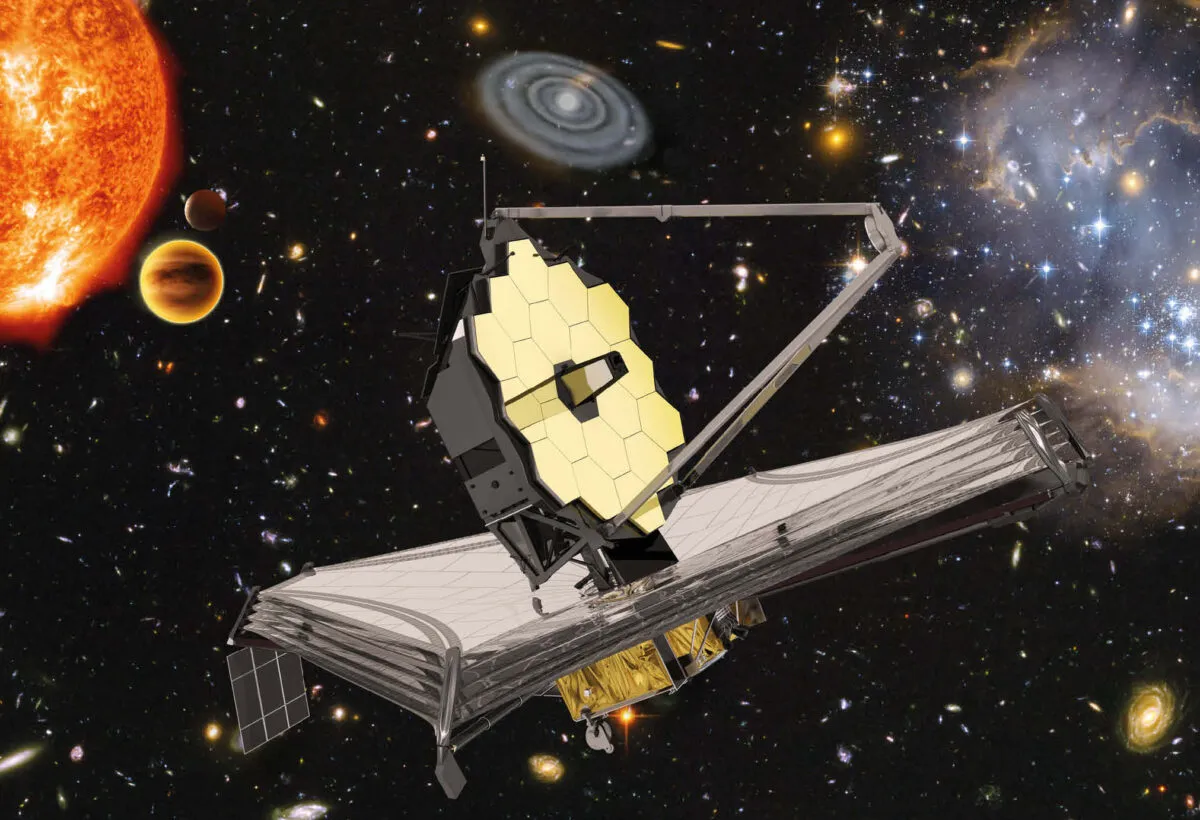

With its tennis court-sized sunshield and 6.5m primary mirror flat-packed inside the launcher like a ship in a bottle, the James Webb Space Telescope is a formidable observing instrument.

Unlike ground-based telescopes and observatories, Webb is a 'space telescope', meaning it operates in space, where it gets a clearer view of the Universe.

See the latest James Webb Space Telescope images

It observes in infrared, meaning it can see things the human eye can't see, enabling astronomers to get a unique view of the cosmos and unlock many of its mysteries.

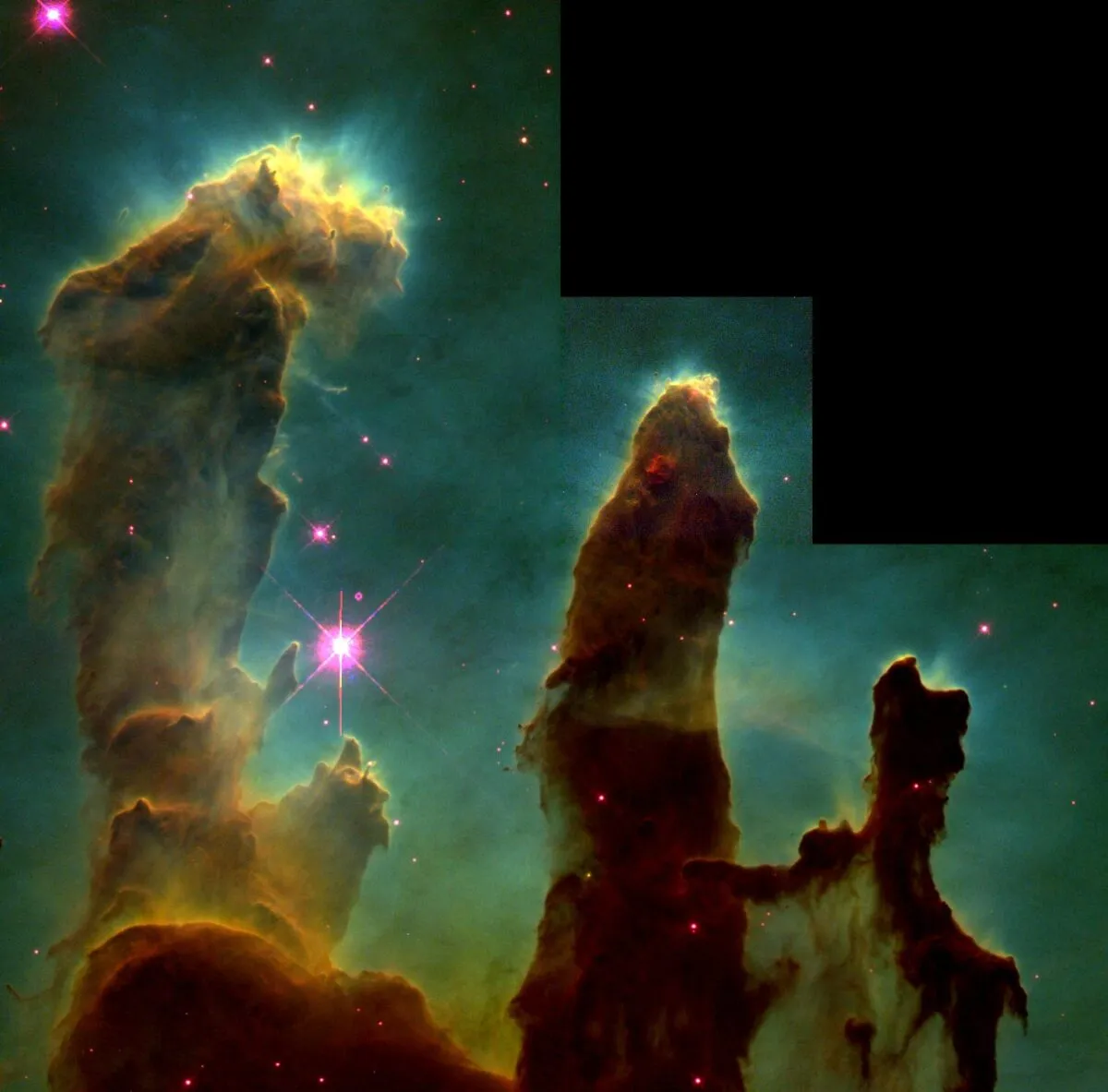

Webb is helping astronomers learn more about galaxies, galaxy clusters, nebulae, exoplanets and the very early Universe.

The James Webb Space Telescope has, in a sense, picked up the observing baton from previous missions like the Kepler Space Telescope, the Spitzer Space Telescope and, of course, the incredible Hubble Space Telescope.

Launch and journey to space

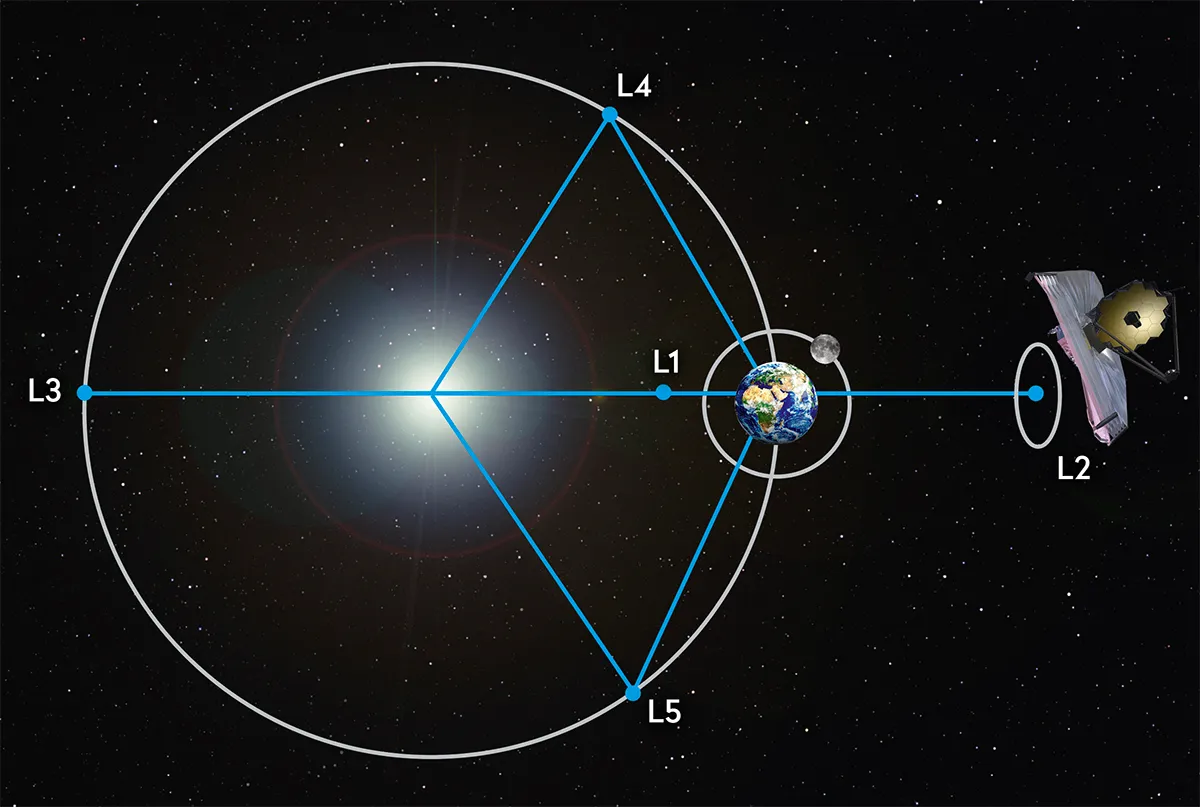

Once launched, JWST travelled over 1.5 million km to a gravitationally stable outpost called Lagrange 2 (L2).

This lies on a straight line from the Sun to Earth and beyond, so JWST is locked into Earth’s yearly orbit around the Sun.

A total of three mid-course correction manoeuvres successfully placed the huge space telescope in a slow looping orbit around the second Lagrange point, 1.5 million kilometres behind Earth as seen from the Sun.

The telescope and its sensitive instruments, which left the French Guiana launch platform at tropical temperatures, had to cool down to 230˚C below zero before science operations could begin.

Thanks to its giant multi-layer sunshield, JWST had already reached –200 °C by early January 2022, but the passive cooling slows down over time.

It’s a delicate process. The optics can never be the coldest parts of the telescope, lest molecules released as gases from the graphite-composite support structure freeze down on the mirrors, degrading its performance.

When the NIRCam instrument (Near Infrared Camera) got cold enough for its sensitive mercury-cadmium-telluride detectors to pick up infrared light, the process of aligning the telescope’s 18 mirror segments could finally commence.

Each of the Webb Telescope's hexagonal segments is fitted with seven actuators and can be slightly tilted, shifted, rotated and deformed to ensure they operate together as one perfect parabolic surface.

The hexagonal mirror is what contributes to the 8 diffraction spikes seen around stars in Webb images.

Testing Webb's instruments

James Webb Space Telescope has four large science instruments:

- NIRCam (Near InfraRed Camera)

- NIRSpec (Near InfraRed Spectrometer)

- MIRI (Mid InfraRed Instrument

- FGS/NIRISS (Fine Guidance Sensor/Near InfraRed Imager and Slitless Spectrograph).

Equipped with beam splitters, filters and micro-shutters, all have different observing modes, and these had to be fully tested and calibrated before they were handed over to the astronomy community.

Astronomers waited a long time to train their new, expensive toy on their favourite objects, be that a remote galaxy at the dawn of time, a planet-spawning accretion disk, an exoplanet’s atmosphere or a denizen of our own outer Solar System.

Yet the James Webb Space Telescope has less pointing flexibility than the Hubble Space Telescope.

Since the telescope must face away from the Sun to keep its instruments consistently cool, its ‘field of regard’ covers 40% of the sky on any given day.

JWST’s mid-course corrections used up less fuel than expected, which means there’s more left to keep the space telescope in its L2 orbit.

As a result, its operational lifetime may be extended beyond the projected operational period of 10 years.

How the James Webb Space Telescope unfolded in space

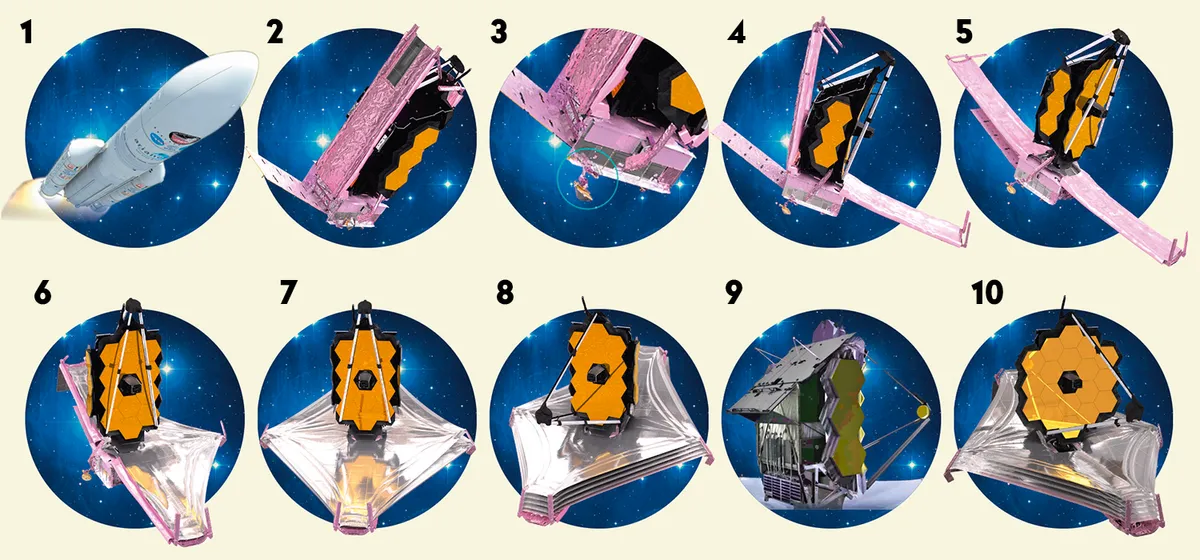

It took more than 50 individual steps and two weeks to for JWST to reach its orbital point and become fully deployed.

Here's a timeline of how it all took place.

- 25 December 2021, 12:20 UT:JWST launches from the Guiana Space Centre on an Ariane 5 rocket; after 27 minutes, it separates from the launcher’s upper stage to travel to L2 alone.

- 25 December 2021, 12:48 UT Deployment of JWST’s 6m, five-panel solar array, which delivers about 1Kw of power. The telescope can now switch from battery power to its own power.

- 26 December 2021: Deployment of the high-gain communications antenna, which allows communication with Earth through NASA’s Deep Space Network.

- 28 December 2021: The Forward Unitized Pallet Structure (UPS), which supports and contains the five folded layers forming the front half of the sunshield, is lowered into place.

- 29 December 2021: The Deployable Tower Assembly (DTA) is raised by 1.2m for better thermal isolation and to give room for the sunshield to unfold in front and behind.

- 30–31 December 2021: Sunshield mid-booms are extended on either side, pulling the folded sunshield layers with them, to form the first part of its distinctive 21m x 14m kite shape.

- 3–4 January 2022: The five Kapton layers of Webb’s sunshield are tensioned. While the Sun-facing side endures temperatures up to 90°C, the shielded side will be as cold as –230°C.

- 5 January 2022:JWST’s 74cm convex secondary mirror is deployed. The foldable structure supporting it has been dubbed “the world’s most sophisticated tripod”.

- 6 January 2022: Deployment of the 1.2m x 2.4m Aft Deployable Instrument Radiator (ADIR), which radiates heat from the space telescope’s science instruments into space.

- 7–8 January 2022: Deployment of the two side panels forming JWST’s 6.5m primary mirror. Its 18 hexagonal segments are made of lightweight beryllium coated with pure gold.

What is James Webb Space Telescope doing?

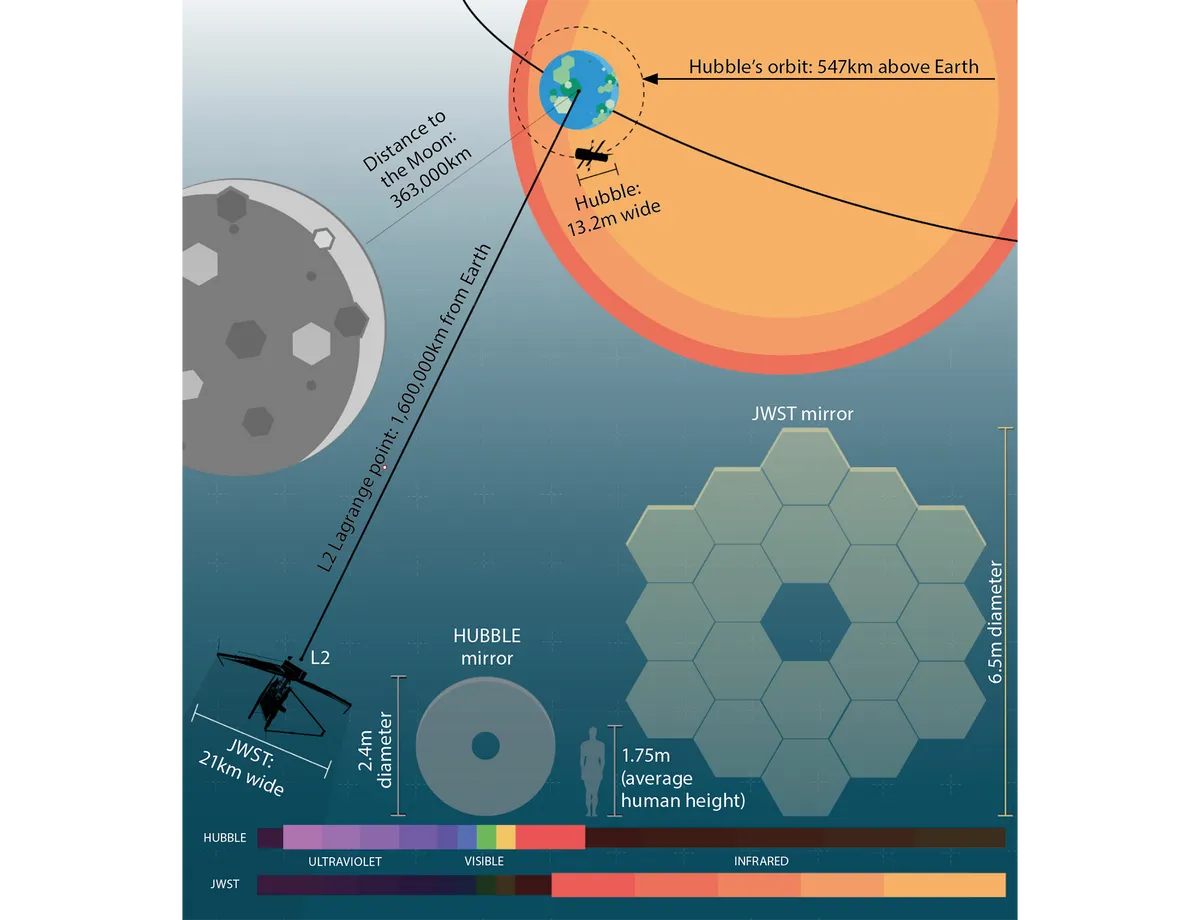

The James Webb Space Telescope - unlike Hubble, which orbits Earth, going in and out of our shadow every 90 minutes - has unobstructed views of the Universe.

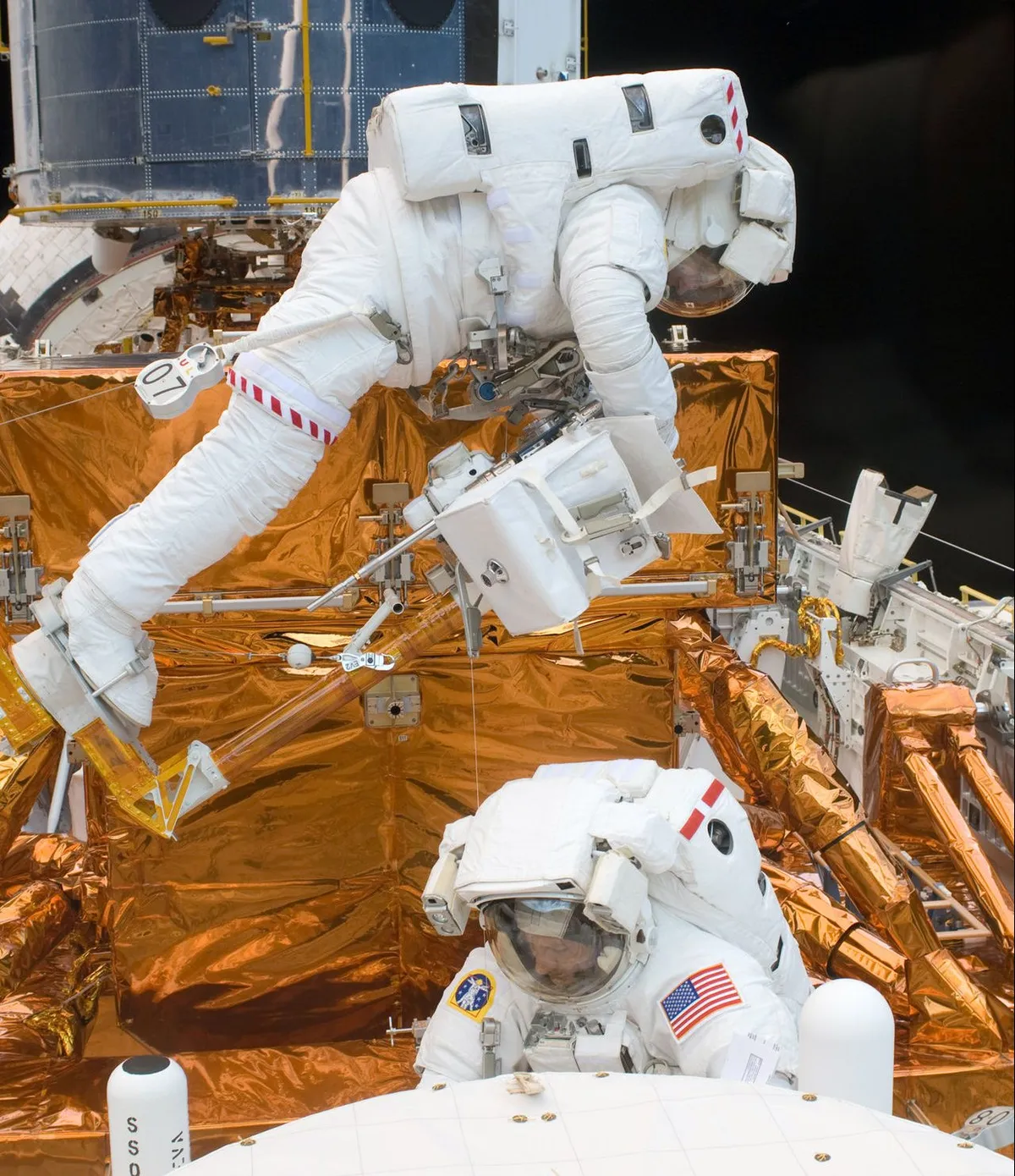

However, the telescope’s far-flung location also means that, unlike Hubble, it cannot be reached after launch and so missions similar to the Hubble servicing missions are impossible.

JWST is hovering at L2 for the next 5.5 to 10 years, and scientists are already finding it is giving us glimpses of the early Universe that we have never seen before.

It is one of the largest, most powerful telescopes and is giving us new insights into every phase of the Universe’s history, from the first dust clouds to our Solar System’s formation.

NASA, one of JWST’s collaborators along with the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Canadian Space Agency, is keen to point out that JWST is Hubble’s successor rather than a replacement.

When Hubble was launched 30 years ago, it was the first space-based optical scope and has given us unprecedented views of the Universe.

However, it looks at the optical, ultraviolet and near-infrared wavelength ranges.

James Webb look sbetween visible red and mid-infrared light, peering much further back into the early Universe.

Light from the earliest luminous objects travels so far in an expanding Universe that by the time it reaches us, its wavelengths have been stretched or ‘redshifted’.

This means that the earliest Universe is observable only in the infrared part of the spectrum.

What might James Webb Space Telescope discover?

JWST’s larger mirror enables it to collect over six times the light that Hubble can, with a field of view 15 times the area of Hubble’s near-infrared camera and spectrometer (NICMOS).

Its primary aim is to probe the so-called ‘end of the dark ages’ after the Big Bang, when the Universe began to fill with ‘first light’ from newly ignited stars.

But like Hubble it is also a general purpose observatory and will specifically look at the birth and assembly of galaxies, the effects of black holes and the origins of life.

Scientists hope JWST will help us better understand the Universe’s size and geometry, throwing light on dark matter and dark energy, and helping us understand the ultimate fate of the cosmos.

Its high resolution means that JWST could give better insights into the Milky Way and our neighbouring galaxies, “extending the work started by Hubble outwards significantly”, according to ESA.

Similarly, its resolution will enable scientists to see how planetary systems form.

One of JWST's tasks is to observe the atmospheres of potentially habitable, rocky exoplanets in the seven-planet system of TRAPPIST-1, 39 lightyears from Earth.

This system was discovered by the Spitzer Space Telescope, which was retired in January 2020.

Like James Webb, it specialised in the infrared range, but JWST is 1,000 times more powerful compared to Hubble.

James Webb Space Telescope vs Hubble

How does the James Webb Space Telescope compare to the Hubble Space Telescope?

Distance from Earth

- Hubble: 570km

- JWST: 1.5 million km

Observations

- Hubble: Optical, UB, to near IR 0.1-2.5 microns

- JWST: Visible to mid IR, 0.6-28.5 microns

What it can see

- Hubble: 'Toddler' galaxies

- JWST: 'Baby' galaxies

Weight

- Hubble: 12,246kg

- JWST: 6,500kg

Diameter primary mirror

- Hubble: 2.4m

- JWST: 6.5m

Size

- Hubble: 13.2x4.2m

- JWST: 22x12m (sunshield)

Main telescope size

- Hubble: School bus

- JWST: Half a Boeing 737 aircraft

Temperature

- Hubble: 21°C

- JWST: -230°C

Interview with a James Webb Space Telescope scientist

Back in 2020, prior to Webb's launch, we spoke to Dr Eric Smith, Program Scientist for the James Webb Space Telescope, to find out more about what Webb will do.

This interview was conducted before the James Webb Space Telescope's launch.

How will the James Webb Space Telescope build on Hubble’s legacy?

Hubble, as amazing as it has been over its 30-year lifetime, has told us there are some things that we would need a different facility to answer.

Hubble in some sense has set up the scientific successor questions that Webb is designed to answer, and the reason Hubble couldn't, say, finish some of the investigations or complete them is because it's got a primary mirror of a given size and its wavelength region is primarily visible.

One of the areas in particular that Hubble pointed us to was the need for a larger infrared telescope to find some of the earliest galaxies.

So Hubble enabled us to know how to build its successor.

Will JWST be able to look back in time at the earliest galaxies?

That's right. Because of the finite speed of light and the very vast distances of space, when we see light from these earliest galaxies, that light left a long time ago on its journey to our telescopes.

So we are seeing back in time to when the Universe was young. Even though these galaxies are very distant, they're actually young when we're observing them and their light has been red shifted by the expansion of the Universe.

The light left those very young galaxies as ultraviolet and visible light, but the expansion of the Universe has stretched its wavelengths into the infrared. And that's why we optimised Webb to work there.

Could we actually see the Big Bang happening?

With Hubble, we can look back to see some of the young galaxies when the Universe was about 500 million years old.

We use microwave background experiments like WMAP or the Planck mission to see the cosmic microwave background, the so-called surface of last scattering, which is when the Universe is three hundred thousand years old.

So in between three hundred thousand and five hundred million years, we don't know what the Universe is doing.It's that period of time we're building Webb to look at.

When did those early galaxies first form? Was it at 200 million years? 300 million years? That's the question.

How was the James Webb Space Telescope built?

The first thing we knew we needed to do was to have JWST work in the infrared.

You know where galaxies emit most of the light and you know how far the Universe has stretched that light, so that tells you what wavelengths you want to optimise for.

For us, that's wavelengths from just a little bit redder than the eye can see out to about 10 to 20 microns. So that tells you your wavelength range.

Now, because these objects are very faint, we know we need a bigger mirror and you can estimate the size of the mirror you need.

Once you know those two things, the rest of the design follows. The interesting thing for us is that our mirror is so big we can't fit it into a rocket when the mirror is just one piece.

So we had to make a telescope that folds up, and it's that feature of Webb that makes it so interesting and its shape so iconic.

Are space telescopes similar to regular telescopes?

Yes. The JWST is a reflecting telescope. It works just the same as the telescopes you buy and use here on Earth.

It looks a little different because we don't have a tube around Webb. Rather, we have a sun shield, which you can almost imagine is like a parasol.

It sits on the side of the observatory that faces infrared bright sources, which for us are the Sun, Earth and the Moon, and then the telescope looks out more or less parallel to that parasol.

We don't need a tube, and the tube itself would have been extra mass that would have made the launch more difficult.

Instead we have this so-called naked mirror and it feeds four different science instruments, cameras and spectrographs.

Where will JWST be located and what will its orbit be like?

Webb needs to be very far away from infrared sources of light or heat. And of course, Hubble being only about 300km above Earth is too close to an infrared source.

So we're going to position Webb about 1.5 million kilometres from Earth at the so-called L2 or second Lagrange point.

These are positions in any two-body orbiting system and were discovered in the late 1700s by a French Italian mathematician, Josephy-Louis Lagrange.

If you put the telescope one and a half million kilometres away, it's far from infrared sources, so you're not blinded by this infrared light locally and you can keep all of them again to one side of you.

This means you only need a sun shield and you don't need a tube.

Webb will follow Earth in its orbit around the Sun: it doesn't orbit Earth, it orbits the Sun.

How will JWST be safe from high temperature or space debris?

Temperature wise, it's much more benign to be at L2.

When it orbits Earth, JWST goes in and out of Earth's shadow, so its exposed to the Sun, then it’s not exposed to the Sun, then it’s exposed to the Sun again. It experiences temperature gradients because of that.

But out at L2 its temperature is much more stable. So that's easier in some sense for us than an Earth-orbiting telescope.

However, it’s not protected by Earth's magnetic fields, and so it’s a little more exposed to cosmic radiation out there.

In terms of micrometeoroids, we more or less know and can calculate the expected number of micrometeoroids of a given size that will hit the telescope over a lifetime.

When we were designing Webb, we knew we had to build in enough capability early on in the mission so that by the end of the mission lifetime, we were still able to do our science.

You more or less build it a little better than you need at the start so that by the time you've taken into account any micrometeoroids, you're still able to do your science.

Is it dangerous that Webb can't be serviced like Hubble?

It's important to remember that while everyone knows about the Hubble servicing missions, there really is only one satellite that was ever built to be serviced, and that's Hubble.

All other satellites are built assuming you will never service them, and the same is the case with Webb, primarily because we're so far away.

We don't have the ability to send astronauts out that far today and we don't have a robot that could do the repairs, so we have to build redundancy in to the design of Webb.

We make sure that in the case of motors that have to deploy things, we have more than one way to address them electrically.

This goes for all other satellites other than Hubble. We don't build in the assumption we'll service it.

We make sure that we test it on the ground to verify it works and build in redundancy so that we don't need to.

If we launched Hubble with technology that we have now, would things be different?

At the time, this notion of a telescope and servicing were intimately linked. In some sense, the Space Shuttle and Hubble pulled each other along as they were being developed.

There's always a debate whether it would have been cheaper to just build another Hubble rather than service it and that's interesting speculation. I don't know what the ultimate answer is.

I think today we know our technology is advanced enough that we don't necessarily need to build in this serviceability. Rather, we can build the smarts into the device itself.

And Webb is a little bit down that path, but today you can build even more smarts into your spacecraft. You could imagine someday even self-healing spacecraft, for example.

Do you mean artificial intelligence that would enable the telescope to fix itself?

You could imagine that in the software, but I'm even thinking, speculating farther out, about materials that could heal themselves.

In other words, it could recognise that it has a micrometeoroid impact and that it needs to repair itself where that happened.

It's much easier to do that on structures that aren't optics. I think self-healing optics is probably a little bit farther down the road.

Is this something that NASA is looking into?

I don't know of any current research programs that are specifically looking at that, but NASA does have an organisation called NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts, which tends to look at really far out ideas like that, just to ask whether there is anything really plausible in that field

And people are incredibly clever, so even though now it sounds like science fiction, someday that will be science fact.

Will JWST discover exoplanets?

Exoplanets is a field that people are keenly interested in right now. And when Webb was actually started, we knew of exactly 2 exoplanets at that time.

But now of course there are thousands and we know of dozens that are Earth-like and nearby enough that Webb will be used to look at their atmospheres using the transit spectroscopy method.

This is when we observe as an exoplanet passes between us and its host star and we measure a spectrum of the star light with the planet in front of it, and then when the planet is not in front of it.

You can use this method to tell what's in the atmosphere of that planet, if it has an atmosphere.

We will be looking for things like water and methane and other kinds of chemicals that could indicate habitability for those exoplanets.

That's something we already know that people are proposing to do with Webb because it's an infra-red telescope.

It also is going to be used to look inside cosmic dust clouds where stars are forming in our own Galaxy, like in the Orion Nebula.

Infrared light penetrates these clouds of dust that block visible light, and so we know there are going to be programs to study the births of stars in these clouds.

Finally, because we can see more or less the full history of galaxy formation, we can watch the Universe assemble galaxies across cosmic time, which means you get the full family picture, from the baby pictures to the grandparent pictures.

Will JWST solve the mysteries of dark energy and dark matter?

In the case of dark energy, astronomers will probably be using or they'll propose to use Webb to help us get better a measure of the Hubble constant.

Right now there's a controversy between the Hubble constant measured through microwave background and through supernova studies.

So people will use Webb to help answer or address that discrepancy.

In the case of dark matter it will again be looking at many galaxies across cosmic time and looking at their rotation curves to see how much dark matter they would contain, and whether that tells us anything different from what we know from just doing visible light studies.

Will James Webb Space Telescope produce beautiful images?

Yes, we designed JWST to be diffraction limited at 2 microns, meaning that the pictures we take in the near infrared will look just as sharp as the Hubble pictures do.

Hubble was optimised for around half a micron. When you put them side by side, they'll be just as sharp.

But they'll be telling us about different aspects of physics because we’re looking at visible light in one instance and infrared light in another.

It's the same sharp detail, but looking at slightly different things. So it'll be fascinating.

How has coronavirus affected work on JWST?

Well, it's certainly an interesting time for everyone in the in the world having to work from home in many cases.

At Northrup Grumman in Southern California, at their Space Park Facility where the hardware is right now, work is continuing on integration and testing, mindful of social distancing and other sorts of considerations we have to take into account. So they are progressing there.

Folks at the Space Telescope Science Institute, the European Space Agency and Canadian Space Agency: a lot of them are working from home.

And there's some work you can do from home, some software development and catching up on paperwork, the kind of things that you get behind with a little bit at the end of a mission.

So work is continuing, although not at the same pace as it as it would.

Of course, we have to take the coronavirus effects into account, and once we come out of this at the other end we'll evaluate our schedule and see how things look.

But it's important to remember that work still is progressing right now. We are all here. A lot of us have been working for many years on it, and we're so close right now, so we're very excited.

This article originally appeared in the May 2020 and March 2022 issues of BBC Sky at Night Magazine