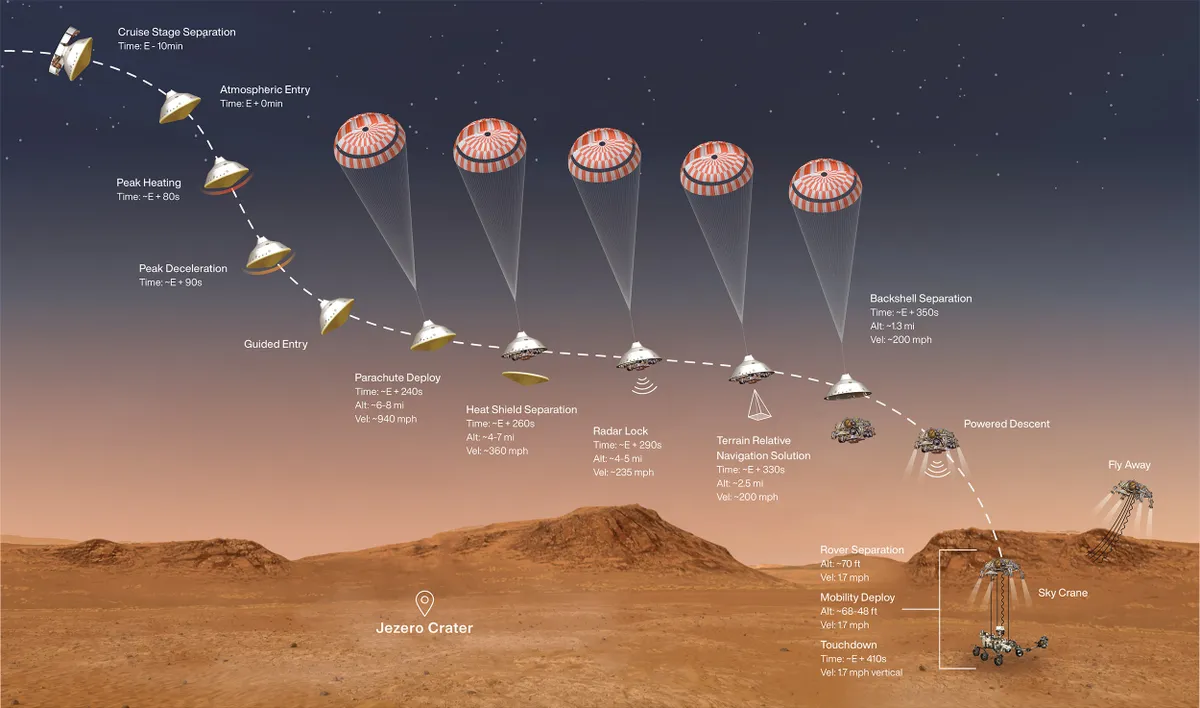

If you’d been standing on the floor of Jezero Crater on Mars on 18 February 2021, you’d have seen a strange sight.

A large vehicle falling out of the peach-hued sky, swinging on the end of a metal line, hanging beneath a Thunderbirds-style contraption that looked more like a huge flying bedstead than a spacecraft.

This was the Perseverance rover, a nuclear-powered geologist-biologist sent from Earth to look for signs of ancient Martian life.

At the end of 2024, the rover finally left Jezero Crater, ready to start the next phase of its mission.

But how did it get there and what has it learned over the past four years?

Why Jezero Crater?

Perseverance was sent to Jezero mainly because the crater contained an ancient river delta, a broad fan of sedimentary material washed into it from the surrounding area by floods billions of years ago.

Here on Earth, river deltas are known to trap and preserve organic materials, making them excellent places to search for signs of ancient life.

Jezero also contained clay minerals, suggesting that water had been present in the crater for a long period, providing a potentially habitable environment for microbial life.

The crater’s flat terrain and lack of large boulders also offered Perseverance a safe landing site.

After landing on Mars, Perseverance set off across Jezero’s floor, ready to begin the first of several planned science campaigns.

With a top speed of 0.1km/h (0.06mph), Perseverance is hardly a racing car, but that’s more than fast enough for a robot scientist exploring an alien world.

And before it could pull on a lab coat, gloves and goggles, it also had to drop off its hitchhiker, a small robot helicopter called Ingenuity.

What Perseverance learned at Jezero Crater

By June, Perseverance had begun exploring the floor of Jezero Crater, stopping regularly to photograph the rocks around it.

But the front of the delta, with its layers of sediment, beckoned, and soon the rover headed for the horizon.

On the way to the delta, Perseverance began using its sophisticated drill to take samples of Martian rock and dust, depositing them into sample tubes and storing them safely on board.

The plan is for these priceless sample tubes to be returned to Earth in the future, but plans for this Mars sample-return mission have fallen into disarray.

NASA deemed the original plan too complicated, too expensive and too slow, so a rethink was ordered.

The problem with Perseverance's Mars samples

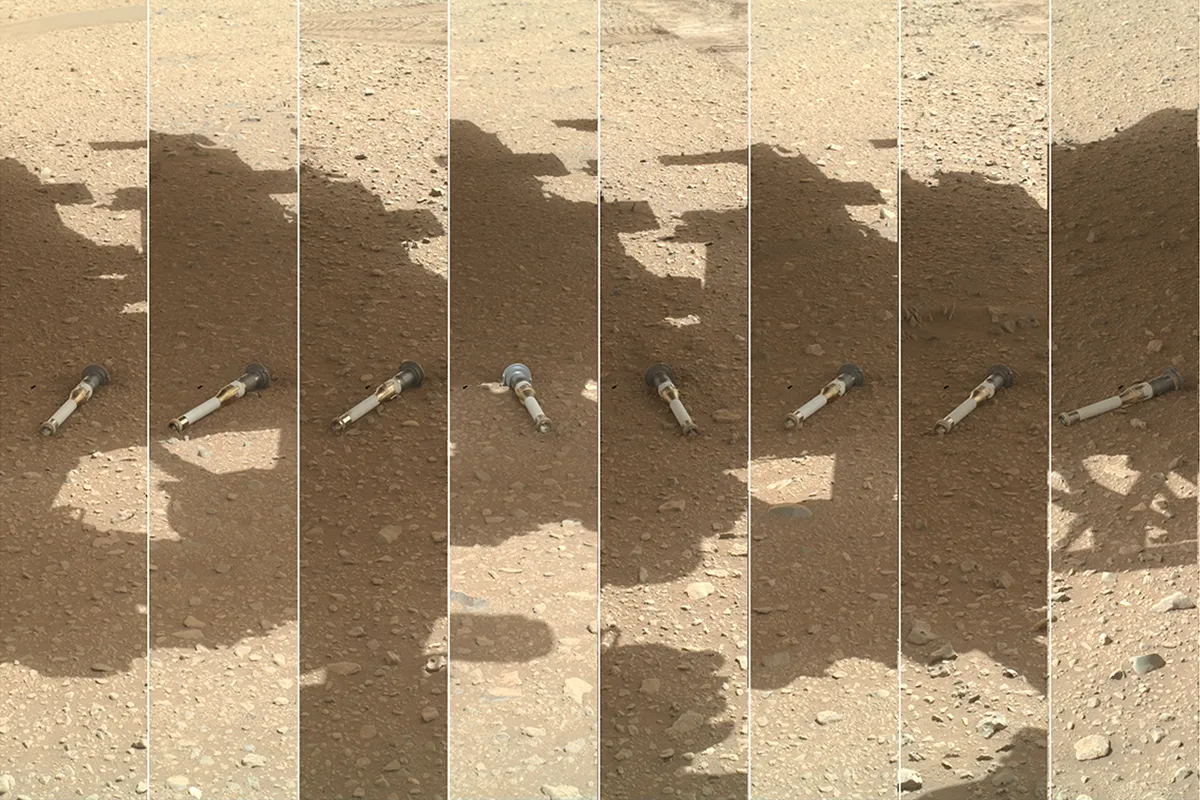

By the time it rolled over the rim of Jezero Crater, Perseverance had taken 18 priceless samples of rock and dust, storing them in metal tubes that look like a cross between lightsabers and giant spark plugs.

The eight most important tubes are stored safely onboard the rover, but 10 ‘backup’ samples were left at a site called Three Forks.

Like a farmer planting seeds, Perseverance carefully dropped the precious tubes onto the ground one by one, spaced well apart, creating what NASA christened a sample depot.

But what’s going to happen to all these tubes?

The original plan was for a complicated joint NASA/ESA mission to retrieve them using a new lander

A pair of Ingenuity-like helicopters and an ascent vehicle to blast off the surface of Mars carrying the tubes up to yet another spacecraft would eventually return them to Earth.

But delays and rocketing costs prompted a fundamental rethink at NASA.

In early January 2025, the agency announced it was planning a cheaper and much less complicated mission, possibly involving private companies, to return the samples in 2035.

A final decision on the way forward will be taken in 2026.

The sounds of Mars

It was during this stage of the mission that Perseverance finally turned the dreams of generations of Mars scientists and enthusiasts into reality.

As well as carrying a shopful of cameras and a small laboratory’s worth of scientific instruments and equipment, the rover is carrying something else: a microphone designed to record the sounds of Mars.

On 20 February 2021, the mic was turned on for the first time.

You might think there’s no sound to be heard on an airless, lifeless world like Mars.

But Perseverance recorded the ghostly whispers of wind gusts and the clanking and squeaking of her own wheels and instruments as she trundled across the rocky landscape.

You can listen to these historic recordings yourself by going to the mission’s website.

Producing oxygen on Mars

Another of the mission’s greatest achievements came in April 2021, when the Mars Oxygen In-Situ Resource Utilization Experiment (MOXIE) was turned on.

MOXIE’s crucial task was to suck in the cold, dry Martian air and see if it could produce oxygen from it – and it worked.

At its most efficient, MOXIE produced an amazing 12 grams (0.4oz) of oxygen per hour, twice as much as NASA originally aimed for.

This proved that the Martian atmosphere can be used on future crewed missions to produce oxygen to breathe and use as rocket fuel.

The revelation could greatly reducing the amount of oxygen needed to be brought from Earth.

Take me to the river

By December 2022, after skirting around craters and dust-trap dune fields, Perseverance finally reached the front edge of the river delta and began working her way along it.

As she drove along in the shadow of the delta, Perseverance looked up and photographed its layers, ridges and outcrops in great detail

The rover carries 23 cameras, all of which serve various scientific, engineering and navigational purposes.

The twin Mastcam-Z cameras are its most powerful, used to take the highest-resolution panoramic and stereoscopic images ever captured on Mars, while the lower-resolution Navcams and Hazcams have helped the rover drivers plan their routes.

Other cameras such as the Supercam and SHERLOC have allowed Perseverance to take extreme close-ups of Martian rocks and features, zooming in on colourful crystals and mineral deposits tantalisingly suggestive of organic processes.

Eventually, Perseverance’s work on the front edge of the delta was done and its drivers steered it carefully up from the crater floor and onto the top of the delta to begin another science campaign.

Here, on the top of the delta, Perseverance was able to study rocks, minerals and structures totally different to the ones on the crater floor.

Driving up a narrow valley into an area christened Bright Angel, the rover found rocks with intriguing sharp ridges crossing them.

Just like a human geologist would do, Perseverance cleaned the dust off the weathered surface of the rocks with its wire brushes and then drilled into them, exposing the pristine, ancient material beneath.

The images Perseverance sent back of one of these rocks, christened Cheyava Falls, had scientists back on Earth leaning forwards in their seats with excitement.

There were small, dark ‘leopard spots’ within them, surrounded by shells or crusts of lighter material, which looked very familiar.

Here on Earth, such structures are often formed by primitive forms of life. Had Perseverance found evidence of life on Mars?

It’s unlikely – these structures can be formed naturally too, by purely geological processes – but scientists are very keen to study the samples collected by the rover to take a much closer look.

Having worked its way up the valley, after investigating a wide variety of rocks and leaving 10 of its precious sample tubes on the dusty ground to be picked up by its successor at some point in the future, Perseverance then set its sights on a new goal.

Like its predecessors, the plucky golf-cart-sized Mars Exploration Rovers Spirit and Opportunity, and its little sibling Curiosity, Perseverance now heard the siren call of the hill summits surrounding it, and began to climb up the rim of Jezero Crater.

Leaving Jezero Crater

Slowly but surely, like a seasoned hiker, Perseverance worked its way up the steep slope, heading for the distant summit.

In mid-September 2024, it spotted something up ahead unlike anything it had seen before.

In stark contrast to the uniformly beige and tan rocks around it, the chalky-pale, 20cm-wide rock off to the side of its route uphill was crisscrossed by darker stripes, like a piece of Martian candy.

Perseverance took detailed photos of this bizarre rock – named Freya Castle by the rover team and thought to have rolled down the slope from outcrops much further uphill – before continuing on its way up the rim.

Looking back down on the floor of Jezero Crater and the ancient river delta it had explored and studied so carefully, it paused to study a large, layered outcrop christened Pico Turquino, sticking up out of the dusty ground like the fossilised bones of some ancient Martian dinosaur, before striking out for the summit.

Reaching the top of the rim

On 10 December 2024, after a hike of four months, Perseverance finally rolled up onto a small, flat area at the top of the crater rim, an area called Lookout Hill.

From there, the rover had a quite spectacular view. Behind it was the rolling landscape it had driven through after landing.

To the southeast was a previously hidden array of mesas, buttes and valleys close to the crater’s far side.

And ahead of it, on the other side of the crater rim, a whole new area of Mars that was until then obscured from Perseverance’s curious eyes by the steep wall of the crater rim, was now in view, lit by the morning Sun.

Like any hillwalker on Earth, the rover paused at the summit to drink in the view and take a sweeping high-resolution panoramic image of the landscape, before starting the long drive down the other side, towards a region of Mars never seen or explored before.

Where next?

After a challenging 3.5-month journey up slopes with gradients as steep as 20% to arrive at Lookout Hill and the rim of Jezero Crater, Perseverance has begun its next phase of operations.

Its fifth science campaign, dubbed ‘Northern Rim’, starts with an area called Witch Hazel Hill, and the rover has already begun the 450-metre (1,500ft) journey towards this layered rocky outcrop.

A feature unlike anything seen inside Jezero Crater, 100-metre-long (330ft) Witch Hazel Hill represents rocks from Mars’s early crust.

During the impact that created Jezero Crater 3.9 billion years ago, huge chunks of rock like it, from deep underground, were lifted to the surface, making it some of the oldest exposed bedrock on Mars.

Each of the outcrop’s layers was laid down at a different time in the planet’s history.

As Perseverance drives along the slope it will become a time machine, using data gleaned from each layer to explore the deep history of Mars’s climate and geology.

After driving down Witch Hazel Hill, the rover will then turn away from the rim and journey 3km (2 miles) to the south, to the plains.

In these grand, sweeping expanses unaffected by the impact that created Jezero, Perseverance has two further scientific stop-offs planned.

What are your favourite moments from the Perseverance mission? What do you think it should study next on Mars? Let us know by emailing contactus@skyatnightmagazine.com?

This article appeared in the March 2025 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine