NASA’s Cassini spacecraft is heading to its Grand Finale on September 15th but its last few dives are still giving new surprising insights into the mysteries of Saturn.

Cassini is currently completing the 15th of 22 weekly orbits, passing through the narrow gaps between Saturn and its rings.

The spacecraft is continuing to measure the planet’s magnetic field, as well as collect the first ever samples of the atmosphere and icy rings.

Launched in 1997, the mission was directed to investigate the structure and key features of Saturn and its surrounding moons.

Since arriving at the gas giant in 2004, it has discovered global oceans on the moon Enceladus, liquid methane seas on Titan and taken spectacular images of the icy rings surrounding the parent planet.

Now the mission is coming to an end, but scientists have not been disappointed by recent findings.

"The data we are seeing from Cassini's Grand Finale are every bit as exciting as we hoped, although we are still deep in the process of working out what they are telling us about Saturn and its rings," says Linda Spilker, Cassini Project Scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL).

Cassini’s magnetometer instrument has revealed that Saturn’s magnetic field appears to be very well aligned with the rotation axis, a surprising find.

The instrument can only measure to 0.06 degrees, and thus far no tilt has been detected.

Planetary magnetic fields are thought to require some tilt in their generated field to sustain the flow of liquid metal in the core of the planet.

Scientists had previously understood that with no tilt, these inner currents would eventually stop and the field would vanish.

With Saturn not showing any tilt so far, observers are having to look for alternative explanations or new theories as to how magnetic fields are maintained.

The tilt of a magnetic field can also be used to measure the length of a planet’s day. But thus far, the length of Saturn’s day has been elusive.

"The tilt seems to be much smaller than we had previously estimated and quite challenging to explain," says Michele Dougherty, Cassini magnetometer investigation lead at Imperial College, London.

"We have not been able to resolve the length of day at Saturn so far, but we're still working on it."

Dougherty and her team, however, think that some part of Saturn’s atmosphere is masking the true tilt.

Analysis will continue up to the end of mission to see whether any new evidence is found explaining this strange orientation of the magnetic field.

While diving between the rings, Cassini has obtained the first ever samples of particles, hopefully giving new insights into the composition and structure of this iconic feature.

Initially thought to be too dangerous, analysis from travelling through the rings has shown that the particles are both very small and benign.

This has led to the spacecraft’s cosmic dust analyzer (CDA) successfully capturing tiny particles from the inner D ring.

In the final orbits and eventual plumet, more samples will be taken and examined with the ion and neutral mass spectrometer (INMS) onboard.

Collections during the final plunge will also give us important data about the composition of Saturn’s inner atmosphere.

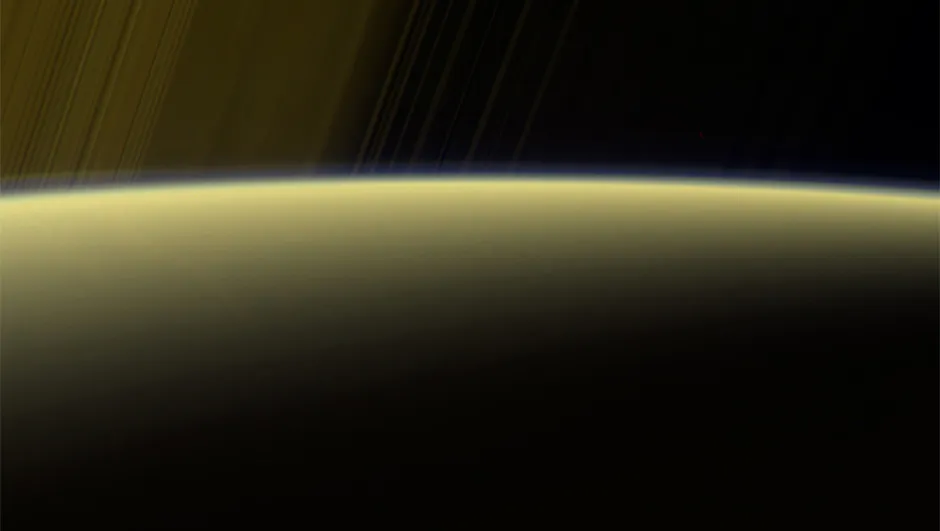

Alongside the scientific investigation of the planet’s inner and outer structure, Cassini is continuing to produce amazing images of Saturn and its rings.

Images include new details on the textures of plateaus in Saturn’s C ring (mysterious bands found on the rings), as well as more ultra-close views of racing cloudscape within the planet’s atmosphere.

"Cassini is performing beautifully in the final leg of its long journey," says Cassini Project Manager, Earl Maize at JPL.

"Its observations continue to surprise and delight as we squeeze out every last bit of science that we can get."