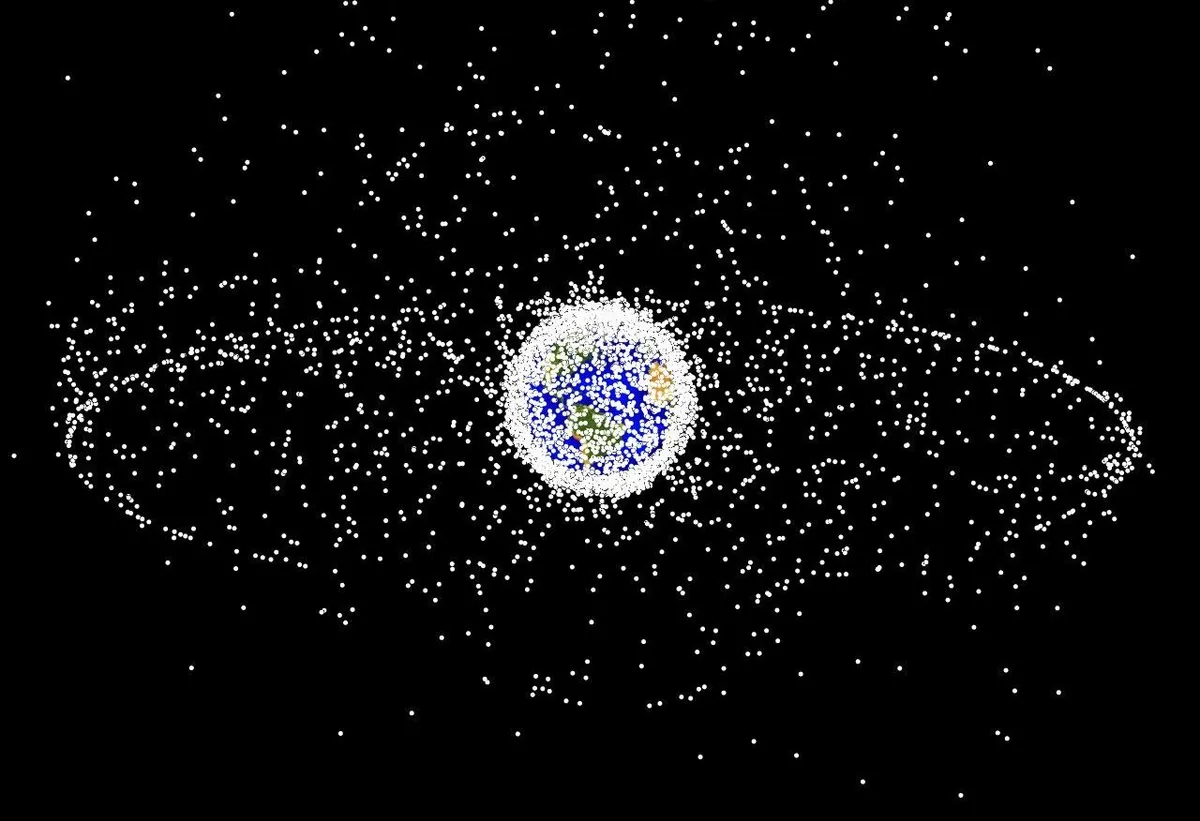

Space is getting increasingly crowded. At least, it is in the region of low-Earth orbit, where many satellites operate.

Spanning altitudes between about 160km and 2,000km above Earth’s surface, low-Earth orbit requires less fuel to reach than higher orbits.

Its relative proximity to the ground also provides advantages for low-powered communication devices, such as Iridium satellite phones (once the cause of Iridium flares), as well as for Earth observation – think weather-forecasting, monitoring the environment and spying.

Read our interview with Dr Space Junk Alice Gorman

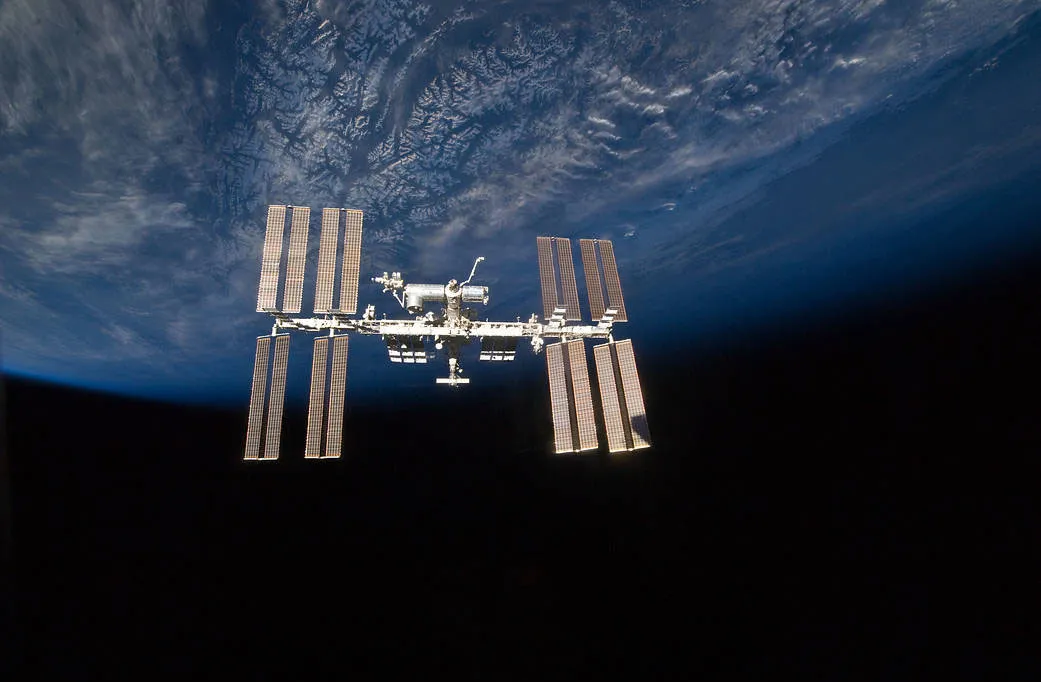

The International Space Station and China’s Tiangong space station also occupy low-Earth orbit, both at an altitude around 400km.

There are plenty of objects like artificial satellites and bits of spacecraft that have fallen out of use and remain in orbit around Earth. These are collectively known as space junk.

Satellites can remain in position long after they have stopped functioning and the process of launching them is also a decidedly messy affair: spent rocket stages and separation bolts also contribute to the debris circling around Earth.

All of this space junk is orbiting Earth at speeds of up to 28,000km/h and as it continues to accumulate it poses an increasing risk of collision.

For example, in the 20 years of its operation, the ISS has had to shift around 30 times to avoid being hit by orbital debris.

But the problem isn’t just the risk of a collision, because a satellite hit by debris can shatter into thousands of fragments, any of which can go on to collide with other satellites and so on.

This could potentially trigger a runaway cascade of satellite destruction – a chain reaction of collisions – until a whole region of orbital space is so full of hazardous debris that it’s rendered unusable or impassable for decades.

This possibility is known as the Kessler Syndrome, and will be familiar to anyone who’s watched the film Gravity (one of our pick of the best space and sci fi movies).

In the worst case scenario, it could block human access to space and end services such as GPS and satellite imaging for a long time.

Could space junk cause a collision?

As more and more satellites are launched into low-Earth orbit, the risk of a catastrophic Kessler Syndrome, and the huge economic impact it would have, only increases. But how likely is it to occur?

Two economists, Akhil Rao, at Middlebury College, Vermont, and Giacomo Rondina at the University of California, San Diego, built a model that not only considers the orbital dynamics involved in a Kessler Syndrome occurring, but also the changing economics of satellite launches.

They note that, currently, orbital space is effectively open access: anyone who can build a rocket is able to place as many satellites as they like in any orbit they choose.

Rao and Rondina focused on the orbital shell, between the altitudes of 600km and 650km, which lies at the edge of the region where Earth’s thin, upper atmosphere will naturally de-orbit debris within 25 years.

Based on the recent growth of the space sector, they calculate a Kessler Syndrome would occur around 2048. But if launches increase more quickly, it could even happen as early as 2035.

Possible solutions to avert the problem include technology to actively remove debris from low-Earth orbit, or new international laws to limit and control the number of launches.

Lewis Dartnell was reading Open access to orbit and runaway space debris growth by Akhil Rao and Giacomo Rondina. Read it online at: arxiv.org/abs/2202.07442.

This article originally appeared in the May 2022 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.