The faceless figure tumbles in the half-light, arms flailing, helmet gleaming in the Sun’s glare.

Below, like a living map devoid of borders, lie the intense blues of the Mediterranean, the rolling greens and tans of Greece and Italy and, further east at his eyeline’s periphery, the snow-dusted peaks of the Caucasus.

Never before has a human’s unhindered gaze seen so much or so far with such clarity, as half of planet Earth comes into view.

On 18 March 1965, this beguiling sight captivated Soviet cosmonaut Alexei Leonov, the first person to ‘walk’ in space.

With stiff-limbed awkwardness, his spacesuit pressurised rigid as a board, he fiddled with the 5.5-metre (18ft) umbilical cable tethering him to the Voskhod 2 capsule.

But his euphoria wouldn’t last, and soon he’d be forced to break every rule in the book to survive.

The first spacewalk

The need for spacewalking was driven by the Moon race between the USA and Soviet Russia.

Working on the airless, radiation-drenched lunar surface made extravehicular activity (EVA) essential, so NASA planned multiple spacewalks in Earth orbit during Project Gemini to prove humans could operate in this environment.

Eager to beat the Americans, the Soviets conceived their own EVA, initially called Vykhod (‘exit’) but later renamed Voskhod 2 to hide its true nature.

Gemini’s solid-state avionics and pure-oxygen atmosphere allowed astronauts to depressurise the cabin and then repressurise it after the EVA.

But Voskhod needed continuous air cooling and would rapidly overheat if the cabin was depressurised.

Weight restrictions also meant extra air couldn’t be carried. The Soviet solution was an airlock, a 250kg (550lb) inflatable fabric cylinder, the Volga.

But the risks were immense. Chief designer Sergei Korolev asked Leonov and Voskhod 2 commander Pavel Belyayev for their opinion, before adding that US astronaut Ed White would perform an EVA very soon.

"He knew how to get our competitive juices flowing," Leonov wrote.

Voskhod 2 was launched on 18 March 1965. An hour after reaching space, Belyayev started inflating the Volga and within minutes the airlock expanded into a rigid edifice 2.5 metres (8.2ft) long and 1.2 metres (4ftm) wide.

Leonov’s 41kg (90lb) spacesuit, the Berkut (‘golden eagle’) had a gold-tinted visor to cut solar glare and a Swiss camera on its chest, a switch sewn into its right thigh.

But that switch lay just beyond the cosmonaut’s reach and the only pictures of the first spacewalk came from grainy automatic cameras.

Belyayev clapped Leonov on the back and uttered one word: "Go!".

Entering the Volga, Leonov closed the inner hatch and began depressurisation. He opened the outer hatch and pushed himself outside.

"When it opened, I was lying on my back," he wrote. "There wasn’t enough space to turn or move much."

Leonov floated into space. "A tiny ant," he recalled, "compared to the immensity of the Universe."

As Voskhod 2 passed within range of the Yevpatoria ground station, the first ghostly images were transmitted to a rapt world.

The spacewalk ended over Siberia, but Leonov’s exertions caused the suit to balloon, rendering it impossible to re-enter the airlock feet first as planned.

His only option was to breach mission rules: bleeding off oxygen to relieve pressure, then diving headfirst into the airlock.

By now up to his knees in sweat, Leonov’s core body temperature rose by 1.8°C (3.2°F), threatening heatstroke.

Turning inside the airlock demanded "tremendous effort", but he managed to close the outer hatch and started repressurisation.

After 12 minutes, humanity’s first spacewalk was over.

Three months later, Ed White completed the USA’s first spacewalk.

Why astronauts do spacewalks

Spacewalks are a vital part of human spaceflight. Between 1998 and 2024, 272 spacewalks built and maintained the International Space Station.

Spacewalkers added new modules, replaced batteries, upgraded solar arrays and rewired power grids. They carried out critical repairs and fixed ammonia and coolant leaks.

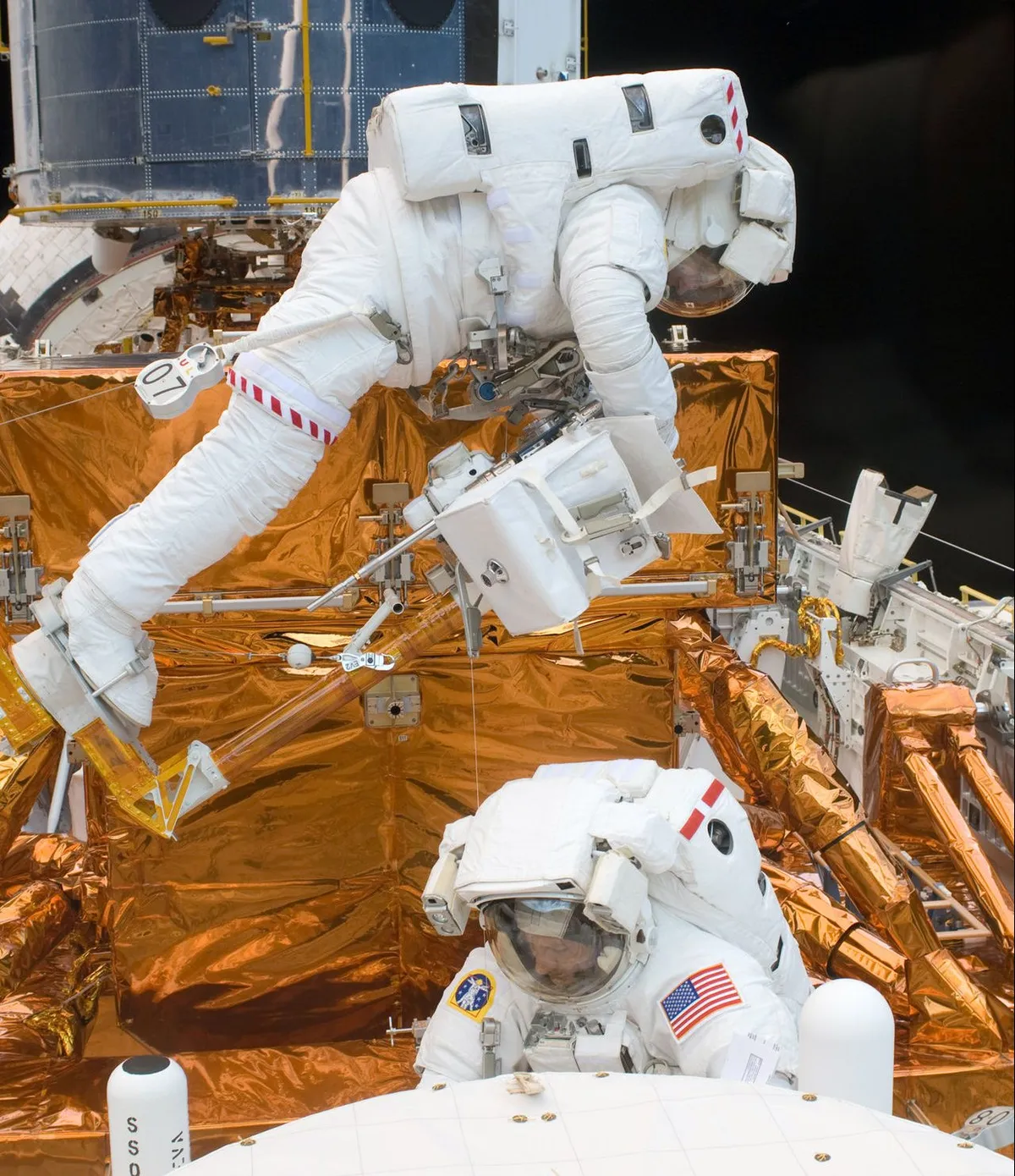

23 spacewalks between 1993 and 2009 serviced the Hubble Space Telescope, adding new optics to correct its blurred vision, changing instruments, replacing gyroscopes, computers and solar arrays, patching insulation and doubling its life.

It continues to dazzle into a fourth decade of service.

10 spacewalks at the US Skylab space station in 1973–1974 added protective solar shields and retrieved camera films.

Russian space station EVAs – three at Salyut 6 in 1977–1979, 13 at Salyut 7 in 1982–1986 and 80 at Mir in 1987–2000 – installed solar arrays and cranes, serviced leaking propulsion systems and inspected damaged modules.

The final Mir spacewalk was the first to be privately funded.

After Zhai Zhigang made China’s first spacewalk in 2008, 17 further EVAs at the Tiangong space station in 2021–2024 assembled a robotic arm, fitted thermal control pumps, inspected solar arrays and installed space debris protection equipment.

Training for a spacewalk entails a mix of parabolic aircraft flights, altitude chambers, virtual-reality exercises and frictionless air-bearing tables to simulate weightlessness and improve spatial and situational awareness.

Large water tanks like Russia’s Hydrolab at Star City, near Moscow, Germany’s Neutral Buoyancy Facility at Cologne and NASA’s 28-million-litre (6.2-million-gallon) Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory in Houston, Texas, afford the nearest experience to the real thing.

To date, 85% of spacewalkers have been Russian or American.

But others have joined this EVA ‘club’: France in 1988, Germany in 1995, Japan in 1997, Switzerland in 1999, Canada in 2001, Sweden in 2006, China in 2008, Italy in 2013, the UK in 2016 and UAE in 2023. The club’s members represent 0.000003 per cent of Earth’s eight billion humans.

Yet just 9.3% of spacewalkers are women.

The first female EVA, lasting three hours and 34 minutes, was by Russia’s Svetlana Savitskaya in 1984.

Since then, US, Chinese and Italian women have upgraded Hubble and assembled space stations, and in 2019 Christina Koch and Jessica Meir completed the first all-female EVA, lasting seven hours and 17 minutes.

Spacewalkers’ ages range from 30-year-old Sarah Gillis, who alongside Shift4 Payments billionaire Jared Isaacman made the first commercial EVA during 2024’s Polaris Dawn mission, to 65-year-old Mike Barratt, whose spacewalk in summer 2024 ended after 31 minutes due to a water leak.

Spacewalk record breakers

Yevgeni Khrunov and Alexei Yeliseyev completed the first two-person EVA, a daring spaceship-to-spaceship transfer in 1969.

Pierre Thuot, Rick Hieb and Tom Akers made a three-man spacewalk to salvage an Intelsat communications satellite in 1992.

And Polaris Dawn saw four humans – Isaacman, Gillis, Scott Poteet and Anna Menon – all simultaneously exposed to the vacuum of space for the first time.

Russian cosmonaut Anatoli Solovyov holds records for the greatest number of spacewalks (16) and spacewalk time (78 hours and 28 minutes).

USA’s Peggy Whitson has the female record, with 60 hours 21 minutes over 10 EVAs.

The longest spacewalk (nine hours and six minutes) was by China’s Cai Xuzhe and Song Lingdong in 2024.

But the shortest is harder to quantify. Gemini astronauts opened the hatch for a few minutes to throw trash overboard.

Apollo astronauts did likewise before leaving the Moon, pushing unneeded gear, waste bags and empty food cartons through the lunar module’s hatch to reduce weight.

The furthest EVAs from Earth were 14 Apollo moonwalks totalling 80 hours and 26 minutes in

1969–1972.

Apollo 15 astronaut Dave Scott also did a 33-minute ‘stand-up’ EVA from the lunar module’s roof hatch to survey the Hadley–Apennine landing site.

"You can move around so much more easily," said Apollo 17’s Gene Cernan, one of only four men to walk in space and on the Moon.

"The human being is a very unique, very adaptable creature."

During the return journey of Apollo’s last three lunar voyages, astronauts made three ‘deep-space’ EVAs totalling three hours and seven minutes at 317,000km (197,000 miles) from Earth and 80,000km (50,000 miles) from the Moon.

"The blackness defied understanding," remembered Apollo 15’s Al Worden. "It stretched away from me for billions of miles."

In 1984, the first untethered spacewalk saw Bruce McCandless test a jet-propelled backpack, the Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU).

It later helped spacewalkers repair the Solar Max observatory and two communications satellites.

The future of spacewalks

Future Artemis moonwalkers will have helmet-mounted HD cameras, advanced 4G cellular communications, sports energy gels for in-suit nutrition and augmented heads-up displays inside their visors.

And eight hours of oxygen and consumables will help them explore more of the Moon than ever before.

In mid-2027, Artemis III astronauts are scheduled to spend a week on the lunar surface and do at least two moonwalks lasting six hours apiece.

The Moon offers an ideal ground to prepare for future Mars missions.

In 2021, NASA’s Perseverance rover landed spacesuit specimens on Mars to assess their performance on the subfreezing, wind-whipped Martian surface.

Dangers

But dangers remain. "There is absolutely no margin for error when walking in space," cautioned Winston Scott, former NASA astronaut who completed three spacewalks during his career.

Spacewalkers have endured bruised hands and torn fingernails, while Luca Parmitano cut short a 2013 spacewalk when water entered his helmet, threatening his hearing and vision.

"Spacewalking," wrote Chris Hadfield, "is like rock-climbing, weightlifting, repairing a small engine and performing an intricate pas de deux, simultaneously, while encased in a bulky suit that’s scraping your knuckles, fingertips and collarbone raw."

Scott Kelly called EVAs "the 'type two' kind of fun: fun when it’s done!"

For six decades, spacewalking has enabled humans to survive in the most lethal environment known.

As we prepare to return to the Moon and head for Mars, future spacewalkers will owe a debt of thanks to Alexei Leonov, the man who made it all possible.

What to wear for a spacewalk

Since Alexei Leonov’s pioneering EVA, six generations of Russia’s Orlan (‘sea eagle’) spacesuit have seen service since 1977.

The earliest Orlans could sustain a cosmonaut for three hours. Today, they routinely support EVAs lasting over seven hours.

Modern Orlans include helmet-mounted lights, rubberised fabric shoulder belts for mobility and flexion, durable gloves and autonomous radios/battery packs.

Inflatable forearm cuffs enable spacewalkers to seal off punctured gloves and since 2009 Orlans carry computers that monitor suit health.

American Gemini and Apollo suits evolved convoluted joints to avoid ballooning under pressure, with greater flexibility and toughened visors.

The Shuttle’s Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU) did away with zippers in favour of a modular design with longer shelf life.

Gloves with silicon rubber fingertips for tactile sensitivity, electronic cuff checklists and wireless video systems add to the EMU’s versatility, which can now remain continuously in service on the ISS for years.

China’s early Feitian suits could support spacewalkers for four hours. But last year, the newest design achieved the longest EVA in history: over nine hours.

Ahead, NASA has contracted with AxiomSpace for improved suits for its Artemis lunar missions.

In 2024, China announced plans for a lightweight suit to support Moon landings, equipped with glare-proof visors, chest-mounted controls and dual helmet video cameras.

This article appeared in the March 2025 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine