For decades humanity has been pushing ever further out into the Solar System, exploring our seven sibling planets and their many moons, as well as countless asteroids.

Yet we’ve done this all from a distance: it isn’t people that have been making the journey, but robotic spacecraft.

More space history

While humans have yet to stray far from Earth, robots have been to the hellish surface of Venus, ranged the hills of Mars and bounced across asteroids.

Their journey has been far from a straight one. Along the way there have been dozens of false starts, fallen hurdles and unexpected twists.

Here are some of the more surprising tales from the journals of robotic planetary exploration.

The Viking mission team photo

In the 1970s, NASA had its sights on Mars. The agency built an impressive pair of spacecraft named Viking which would, they hoped, take the first ever panorama from the Red Planet’s surface.

With such an important task resting on having cameras that worked, it was with horror that Thomas Mutch, the head of the Viking landing team, discovered that the engineers intended to send the instrument to Mars without having taken a test photo.

The build team reassured him that if they tested every component separately then the whole instrument would definitely work, but he was sceptical.

After much haranguing, Mutch convinced them to let him take the camera for a test drive.

The team took a quick test photo in the car park at ITEK where the cameras were being built, before loading millions of dollars of irreplacable equipment into a van and then driving to a national park, to test them in a more ‘Mars-like’ environment.

As the test went smoothly, the crew took a quick team photo, taking advantage of the camera’s slow scanning speed to run around the back and appear in the image multiple times.

Opportunity rover comes unstuck

On 29 June 2003, the Opportunity rover was on top of a Boeing Delta II rocket, ready to begin its voyage to Mars after being delayed due to bad weather.

Inspectors were busy checking the rocket to see if it had been damaged overnight when they discovered something peeling off the side of the launcher: a layer of cork.

You read that right: cork. Delta rockets are coated in a layer of the tree bark to help distribute heat during take-off.

In this case, several of the panels had been put on sideways, allowing water to seep in and dissolve the glue.

With the launch window rapidly advancing, the Boeing engineers exchanged frantic phone calls with the adhesive manufacturers, trying to get the panels stuck back on.

Fortunately, they managed it and on 7 July, 11:18pm local time, Opportunity began its journey to Mars.

Only a few of the build team had stayed behind to watch the late launch but among those few were a pair of bagpipe players, Mary Mulvanerton and Jon Beans Proton, who accompanied the launch with the comforting drone of Amazing Grace.

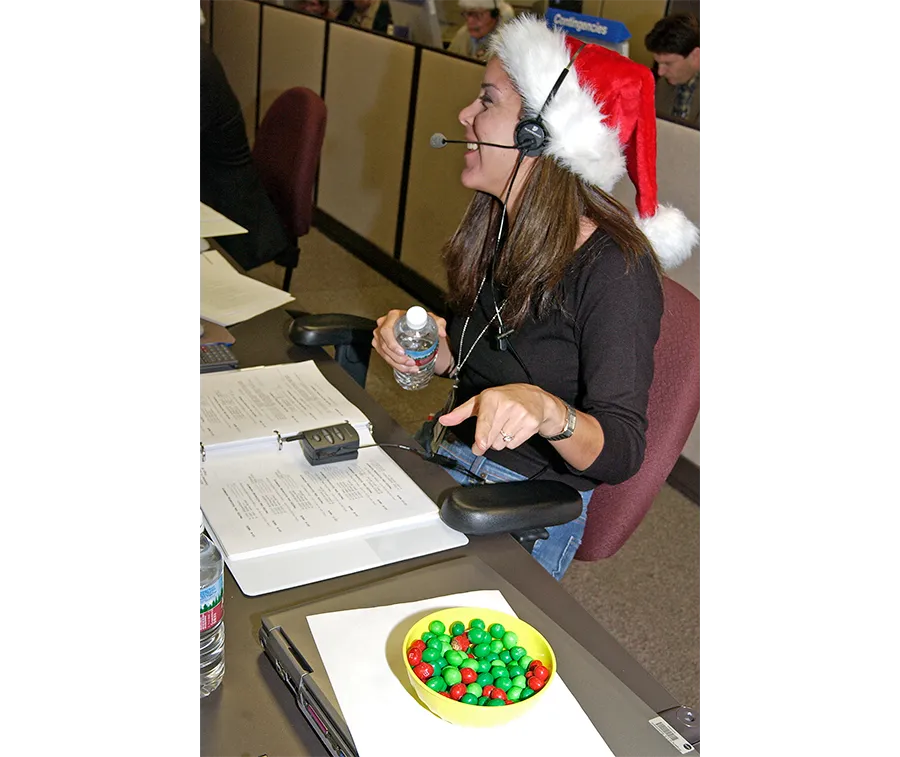

NASA's lucky peanuts

In the early 1960s, NASA was not having much luck with lunar landers.

Its Ranger project was meant to be destructively impacting a spacecraft into the Moon, taking photographs as it went.

Yet, after 6 attempts NASA hadn’t even been able to crash onto the Moon.

NASA’s luck finally turned on 31 July 1964, when Ranger 7 impacted.

The reason for the success: careful engineering and learning from past mistakes… or was it the fact that someone had brought peanuts into the control room at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) that day?

Whichever is actually responsible, tradition has deemed that it was the ‘lucky peanuts’ that did the trick.

Ever since, almost every major planetary milestone controlled from JPL has been watched over by the auspicious nibbles.

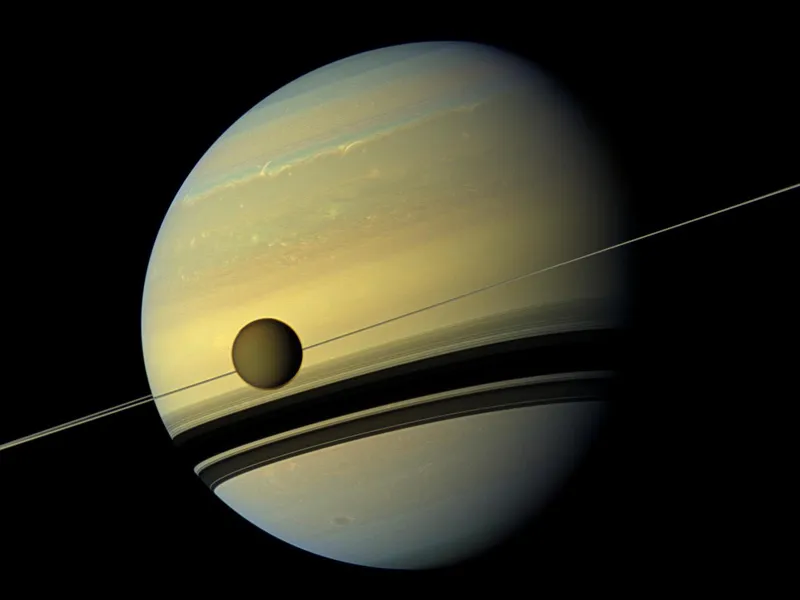

Normally these are jars of regular peanuts, but when Cassini released the Huygens lander towards Saturn’s moon Titan on Christmas Eve 2004, it was festive bowls of red and green M&Ms – the peanut variety, naturally – that were spread throughout the control room.

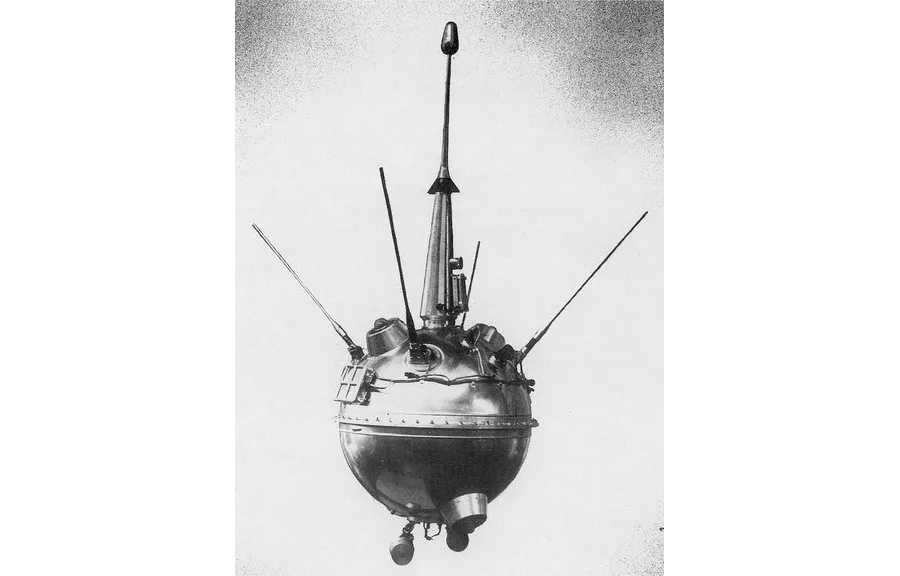

The Space Race doesn't stop for cricket

In the early days of the Space Race, the Soviets were very much in the lead: Sputnik had been the first satellite in orbit; the ill-fated dog Laika was the first living animal in space; and the Soviet Luna 1 had been the first spacecraft to reach the Moon’s vicinity.

However, the Soviets had a policy of not announcing their missions until they’d already been successful, leading to allegations the whole thing was a communist conspiracy: the Great Red Lie.

These suspicions were largely swept away, however, by the huge radio telescope at Jodrell Bank, just outside Manchester, which was watching every mission and could clearly see their radio signals emanating from space.

On 13 September 1959, the Soviets were preparing for their Luna 2 spacecraft to not just pass the Moon but to crash into it.

It would be the first time humanity had actually contacted another world and the Soviets didn’t want there to be any doubt.

They wanted the observatory’s director himself, Bernard Lovell, in the control room.

They really should have checked the schedule ahead of time, however, as the landing fell on a Sunday and Lovell had far more pressing matters to attend to: umpiring his local cricket match.

Initially, Lovell refused to even contemplate returning to work. It was only when he received a call from the top brass in Moscow that he ditched his cricket whites and returned to Jodrell Bank to watch the historic event.

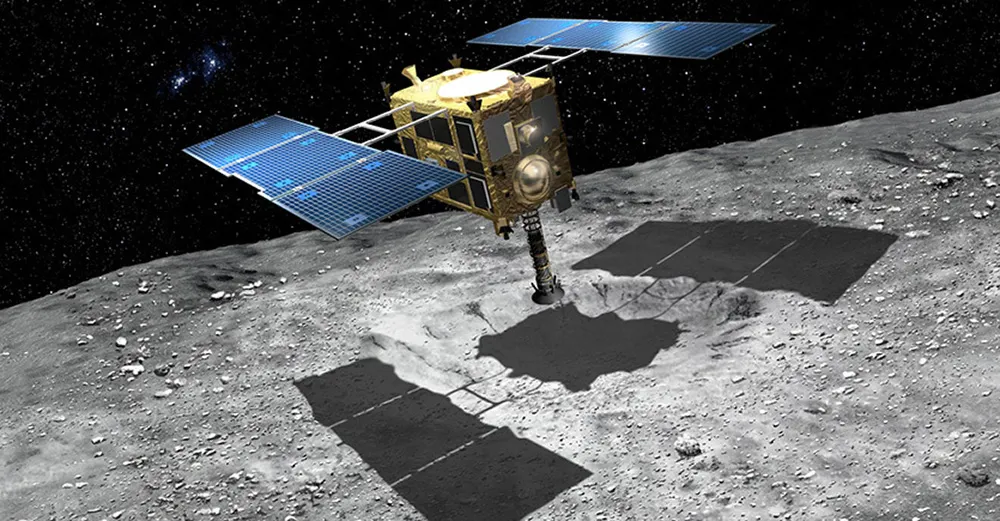

Hayabusa: the unluckiest spacecraft?

Launched on 9 May 2003, the asteroid-investigating mission Hayabusa was one of the first planetary spacecraft of the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA). Its mission was to approach asteroid Itokawa, take a sample of space rock and return it to Earth.

While at first the spacecraft sailed on smooth seas, things took a turn for the worse in November 2003 when the largest solar flare on record erupted, washing straight over Hayabusa.

The radiation severely damaged the spacecraft’s solar panels. But Hayabusa flew on, arriving at Itokawa in September 2005 only to reveal that two of the three reaction wheels that kept the spacecraft steady were broken.

Then when the spacecraft attempted to release a mini-lander, known as MINERVA, a safety protocol caused it to back off at the last minute and release the lander from completely the wrong place.

Things only got worse when Hayabusa itself moved in to take its rock sample. It ended up spending half an hour lying on the rock, soaking in its heat, without deploying its sampling instrument.

After a second attempt also failed, JAXA decided to bring the spacecraft home in the hope that some asteroid dust might have been swept up in all the confusion.

But when Hayabusa briefly lost communications with Earth, it missed the window of opportunity to launch – its journey would now take another three years. It finally arrived back in 2010, with less than a milligram of material onboard.

The mission's follow up, Hayabusa 2, is currently in operation.

No money for a Mars mission

In 1991, the Soviet space programme was hard at work on Mars 94, due to launch within three years.

While things had been going well for the mission, the same wasn’t true of the nation, and in December the Soviet Union collapsed to become Russia and the Commonwealth of Independent States.

The Mars 94 mission now found itself spread across multiple countries, each of which was frantically trying to set up something resembling a stable government.

As space wasn’t high on anyone’s funding priority lists, the mission made faltering progress as money dripped in and ran out.

The launch was pushed back and Mars 94 became Mars 96, while nationwide power cuts meant a spacecraft intended to travel to the stars was being built by unpaid workers, operating by candlelight and being kept from freezing by kerosene heaters.

Mars 96 did make it to the launch pad, but not much further. After failing to reach orbit, the lander – and its plutonium power source – dropped somewhere into the rainforests of Chile.

As the Russians couldn’t afford to retrieve it, no one is really sure of its whereabouts to this day.

Remember to remove the lens cap!

The surface of Venus isn’t the best environment to operate a spacecraft in.

The surface is hot enough to melt lead, while the pressure is 92 times that of Earth at sea level and the air is filled with caustic chemicals.

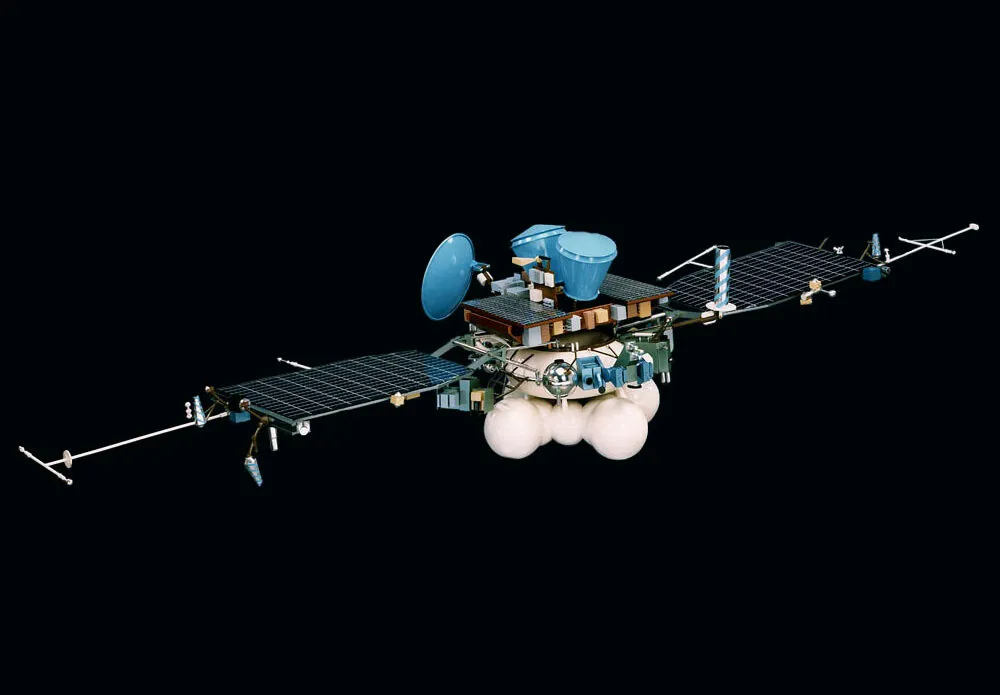

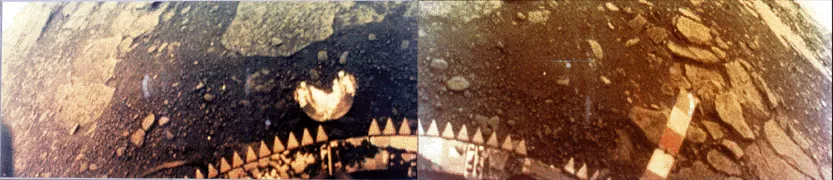

Yet, it was the Soviet Union’s Venera missions to this hellish world that were the nation’s most successful planetary campaign, and one of the most memorable in the history of Venus exploration.

The initial landers were simple, but by the time the Venera 9 and 10 spacecraft touched down in October 1975, they had been refined enough to be equipped with a pair of black and white cameras that would take the first ever image from another planet’s surface.

The pressure had been too much, however, and both of the landers ended up with one of their lens caps sticking.

Though they couldn’t capture the full 360º panoramas they’d intended to, the images still grabbed headlines around the world.

When the next pair of Venera missions, 11 and 12, came around in 1978, they’d been upgraded with colour capable cameras… so it was even more galling when the ‘images’ came back and revealed that every single lens cap on both rovers had been stuck yet again.

By the time Venera 13 touched down in 1982 the problem had finally been fixed and it could take its colour photos with both cameras.

Air conditioning can be a blast

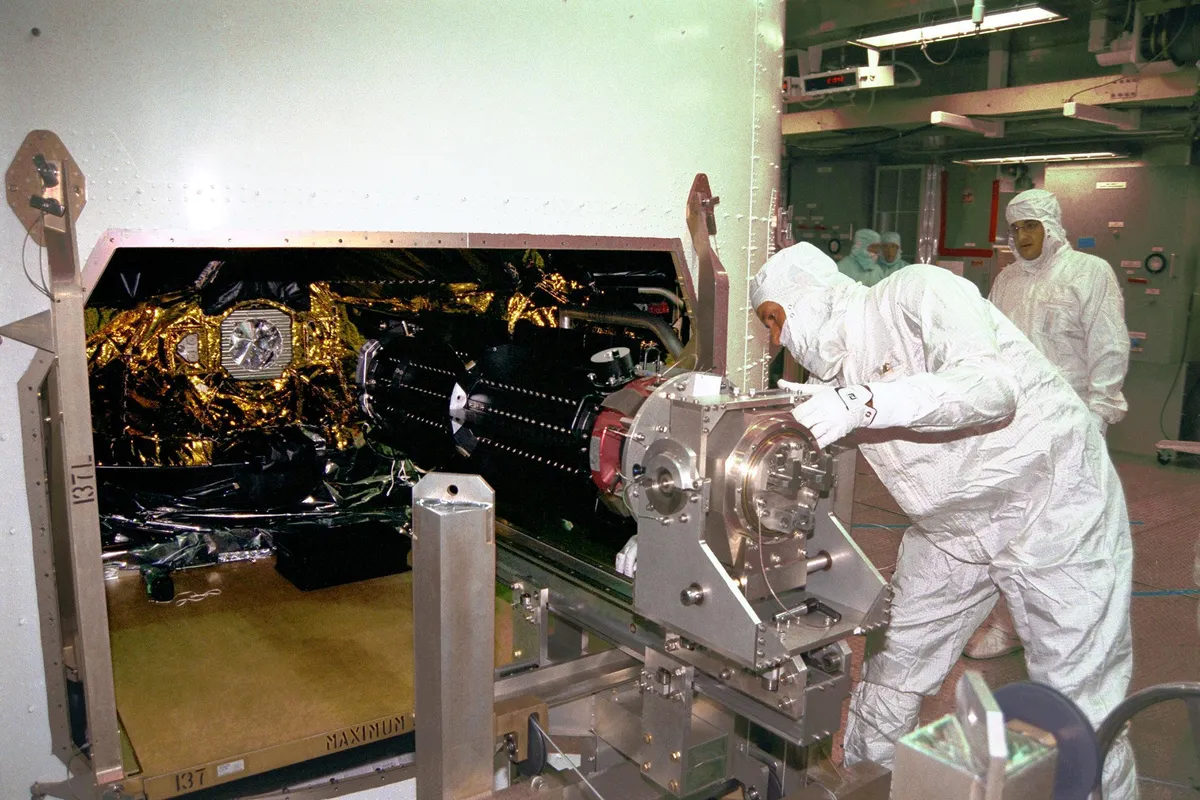

At a distance of 1.5 billion km from the Sun, Saturn is a dim planet. As such, NASA couldn’t rely on solar panels when they were designing the Cassini spacecraft to investigate the planet.

Instead they used a radioisotope thermoelectric generator, which converts heat from a radioactive brick of material into electricity.

These also have the added benefit of working as a very efficient heater to keep your spacecraft warm in the cold of space.

You can’t turn off a nuclear heater, however, and this created something of a problem when, in the autumn of 1997, Cassini was being prepared for launch at Cape Canaveral in the Florida heat.

The spacecraft had to be constantly air-conditioned but, when the fans were turned on, the blowers had been set 10 times too high.

The powerful air blast shredded the spacecraft’s insulation, firing small particles through the billion-dollar spacecraft.

The crew had to rapidly unload the spacecraft, clean it out and hope there wasn’t any damage they couldn’t see. As the Cassini mission would go on to last almost 20 years, it seems they were okay.

A memorial on Mars

On the morning of 11 September 2001, Steven Gorevan of Honeybee Robotics was heading into the company’s office in lower Manhattan.

He and his team were due to spend the day working on the rock abrasion tools (RATs) – instruments which grind away a rock’s surface to reveal pristine material beneath – which the company was building for NASA’s Mars Exploration Rovers, Spirit and Opportunity. But he never started work that day.

While cycling into the office at 8:46am, Gorevan heard the sound of an aeroplane overhead flying unusually low, just before it impacted with the North Tower of the World Trade Centre, six blocks away.

In the weeks following the 9/11 attacks, the staff at Honeybee struggled to return to normal. JPL engineer Steve Kondos, who was working with the team, wondered if they could include some of the wreckage of the towers in the instruments.

They contacted the offices of Mayor Rudi Giuliani and a few days later a box was delivered to the Honeybee office. Inside were a few fragments of twisted metal and a note reading ‘Here is debris from Tower 1 and Tower 2’.

The Honeybee team reverently crafted these pieces into two cable guards to protect the RAT during drilling, each decorated with an American flag. Though the rovers are no longer operating, the cable guards still stand on Mars, a permanent memorial to those who lost their lives on 9/11.

This article originally appeared in the February 2021 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.