By May 1969, the US was almost ready to land on the Moon.But before NASA was willing to risk human lives on the landing, they wanted a dress rehearsal to make sure that everything was ready to go.That mission was Apollo 10.

Over eight days, the crew of Apollo 10 would perform a mission that was identical to the future lunar landing in every way bar one – they wouldn’t touch down on the lunar surface.

It was the same mission duration as Apollo 11, with the same orbit and the same spacecraft, so what stopped NASA allowing Apollo 10’s crew to land on the Moon?

The main reason was that there were still some uncertainties surrounding calculations involving the Moon’s gravitational field, which needed further investigation.

The powered descent guidance system on the lunar lander needed to be accurate to within one nautical mile (1.85km) for the eventual Apollo 11 landing to be successful.

There was still much to learn from this mission.

Launch date: 18 May 1969

Launch Location: Launchpad 39B, Kennedy Space Center

Lunar Orbits: 31

Mission Duration: 8 days, 3 minutes, 23 seconds

Return Date: 26 May 1969

Main goals: Dress rehearsal for Apollo 11

Firsts: Live colour TV transmission from space; highest speed by a crewed vehicle (39,897km/h); first human to fly solo around the Moon (John Young); shave in space

Menu: Beef and vegetables, pineapple fruitcake, orange-grapefruit drink, grape punch

There was a risk here: a crew as capable and experienced as Apollo 10 might go rogue and attempt a landing anyway.

After all, these were veterans of the Gemini programme and had been the back-up crew for Apollo 7.

Thomas Stafford and Eugene Cernan could easily have grazed the Moon when testing the lunar module.

And while NASA doubtlessly trusted the crew, this temptation had been factored into mission design.

“A lot of people thought about the kind of people we were”, said Cernan.

“The ascent module, the part we lifted off the lunar surface with, was short-fuelled. The fuel tanks weren’t full. So had we literally tried to land on the Moon, we couldn’t have gotten off.”

For Stafford, Young and Cernan, it was finally the chance to go beyond low-Earth orbit; to the Moon.

A sizeable achievement in its own right and for them, that was enough.

They were a team after all, and they hoped that their chance to walk on the Moon would come later.

Indeed, Cernan became the last man on the Moon, as part of the Apollo 17 mission.

Every element of Apollo 10 was about final checks, and the crew was committed to fulfilling this brief.

Successful lift-off

Apollo 10’s launch into lower-Earth orbit went without incident.

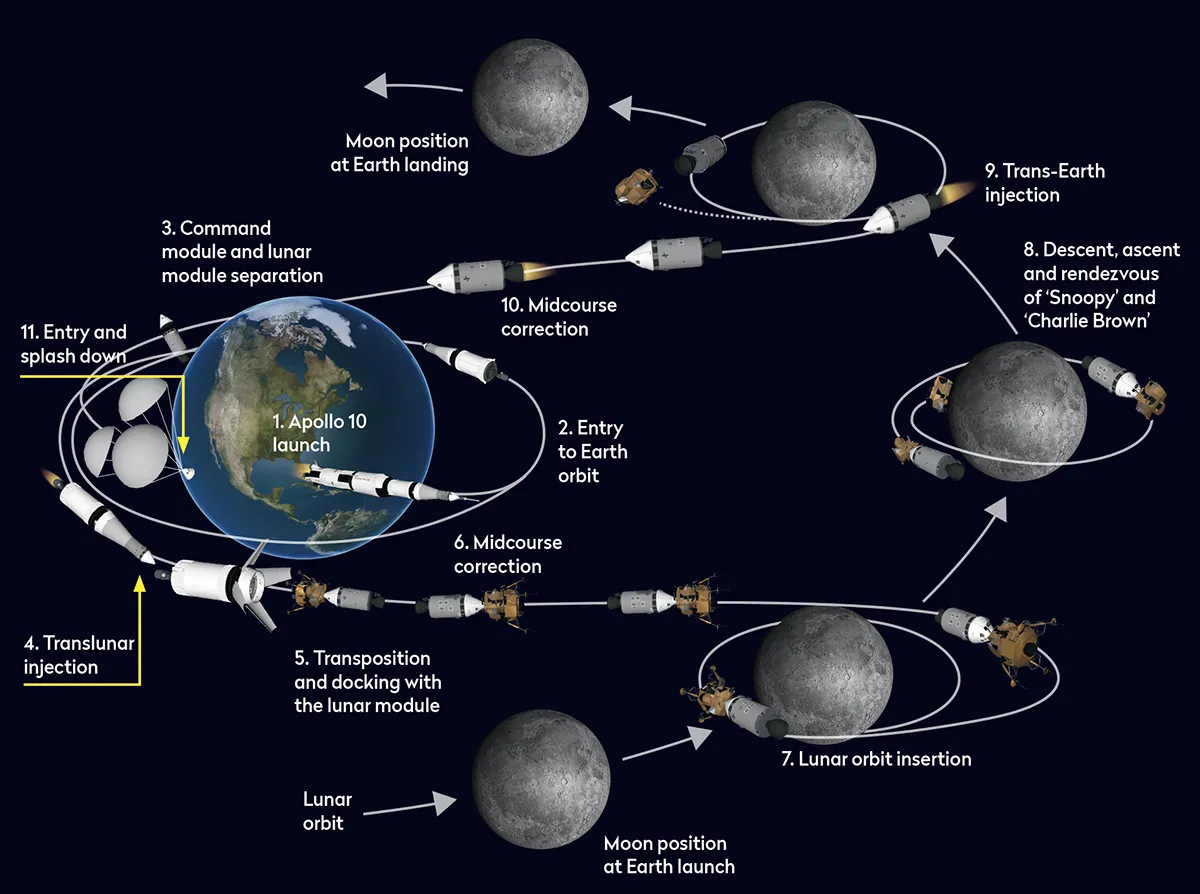

A little over two and half hours later, after 1.5 Earth orbits, the translunar injection was initiated, increasing the speed of the spacecraft to the velocity required to escape Earth's gravitational pull.

Shortly afterwards, the crew transmitted the first colour broadcast from space as they extracted and docked with the lunar module, named ‘Snoopy’ in reference to the black and white caps the astronauts wore, which resembled the cartoon character.

The command module was named ‘Charlie Brown’, continuing the theme.

Apollo 10’s outward journey proceeded almost exactly as planned.

Thanks to the gravitational drag of Earth, the 39,000km/h velocity at which it entered the lunar corridor was reduced to approximately 3,200km/h.

Then, as the spacecraft entered the Moon’s gravitational field, the pull of the Moon overcame the braking effect of Earth and the spacecraft picked up speed to a peak of 8,850km/h (relative to the Moon) just before entering lunar orbit.

To achieve orbit, it was necessary to use the Service Propulsion System to slow the spacecraft’s speed to roughly 5,800km/h and permit its capture by the Moon’s gravitational field.

They arrived in lunar orbit on the third day.

Refreshed by what Stafford termed “a great night’s sleep” and feeling “just tremendous,” the spacecraft commander played a tape of Andy Williams singing “Up, Up and Away!”

They had time for TV broadcasts, where Cernan displayed drawings of Charlie Brown in space coveralls, and his toy beagle Snoopy wearing the scarf of a World War One fighter pilot.

Stafford and Young were shown side by side, with Young upside down.

To demonstrate the strange effect of weightlessness, Stafford would move Young up and down with little more than a light touch as Young joked, “I do everything he tells me.”

Food on this mission had improved a lot from previous Apollo missions and boosted crew morale as they travelled on their outward journey to the Moon: individually wrapped commercial bread and the ingredients for ham, chicken and tuna salad were added to the usual freeze-dried diet.

However, the drinking water didn’t go down so well, with a discernible after taste of chlorine with each gulp.

Gee, I’m really getting vertigo here!

Thomas Stafford, drifting over the Moon in ‘Snoopy’

Flying over the Moon’s surface

Then came Thursday 22 May, day four of the mission and the most action-packed.

The time had arrived for lunar module ‘Snoopy’ to descend to the Moon.

While Young remained in lunar orbit on ‘Charlie Brown’, Stafford and Cernan entered the lunar module and slowly backed it away from the command module.

For the next eight hours, as Cernan and Stafford completed their checks, standing throughout, Young became the first person to fly solo around the Moon.

It was mid-afternoon in Mission Control before everyone was ready and then around 9.35pm GMT, the descent engine fired, bringing ‘Snoopy’ closer to the Moon’s surface than ever before.

An hour later, Cernan excitedly commented, “Hello Houston, we is [sic] down among it!”

They had reached 8.4 nautical miles (15.6km) above the Sea of Tranquility, Apollo 11’s planned landing zone, all the while describing the lunar surface that was passing beneath them, giving the landing radar a thorough checkout and conducting extensive surface photography and landmark tracking.

The lunar module flight was near flawless apart from one chilling moment, as they were preparing to disembark from the lunar surface.

Due to a misaligned switch on the ship’s abort guidance system, ‘Snoopy’ suddenly began to spin and gyrate wildly.

Caught off-guard, Cernan shouted “Son of a b——!” live on the radio, across an open channel to the world.

Thankfully control was regained after a few seconds, and the gyrating spacecraft returned to a normal ascent.

A relieved Stafford announced to Mission Control, “We’ve got all our marbles.”

The rendezvous with the command module went without incident.

The two craft joined up on the far side of the Moon, and when the crew re-emerged, Stafford radioed, “Snoopy and Charlie Brown are hugging each other.”

To celebrate, Mission Control in Houston displayed a large cartoon showing Snoopy kissing Charlie Brown.

After eight hours apart, Stafford and Cernan re-joined Young in the main craft.

The lunar module was cast loose and fired its engine driving it into orbit around the Sun.

Friday 23 May was a day of relaxation and recovery for the crew in lunar orbit.

They completed some landmark tracking and lunar photography and more TV broadcasts.

When the camera focused on the crew, they had shaved: another first.

Previous Apollo crews had ended the mission sporting significant stubble due to concerns that shorn hair might escape in the cabin and cause difficulties with the instruments.

Apollo 10’s crew avoided this by using tubes of shaving cream and capturing their scrapings in swabs.

“We felt reborn,” Cernan later recalled in his autobiography, TheLast Man on the Moon.

As they left lunar orbit, with a velocity of 39,897km/h, they set a record for the fastest speed ever achieved by a human being.

Apollo 10 splashed down east of Samoa on 26 May, and the crew were recovered and flown to Houston for de-briefing.

A large sign had been put up on Mission Control which read “51 days to launch”.

Focus had already shifted to the Apollo 11 mission.

Stafford, Cernan and Young had done their part. Now it was time for Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins.

You can see Apollo 10’s ‘Charlie Brown’ at the Science Museum in London which is on permanent display.

‘Snoopy’, meanwhile, is in permanent orbit around the Sun.

Meet the Apollo 10 astronauts

Commander: Thomas Stafford

Originally a US Air Force flight instructor, Stafford was selected for NASA’s Gemini programme in 1962. He was back-up pilot for Gemini 3, pilot for Gemini 6 and command pilot for Gemini 9. After commanding Apollo 10, he commanded the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project in 1975, a joint US & Soviet space flight, before retiring.

Command module pilot: John Young

A navy test pilot before joining NASA in 1962, Young first flew in space on Gemini 3. After Apollo 10, he went on to be commander of Apollo 16 in 1972 and became the ninth man to walk on the Moon. He commanded the first and ninth Space Shuttle launches, in 1981 and 1983, both aboard Columbia. He died in 2018 aged 88 years.

Lunar module pilot: Eugene Cernan

Pilot Gene Cernan joined NASA in 1963. His first space mission was Gemini 9 in 1966 when he made the second American spacewalk. After Apollo 10, he returned to the Moon in 1972 as commander of Apollo 17 and became the final astronaut to walk there – the last of only 12 people to have walked on another world. He died in 2017 aged 82.

You can’t imagine the position we can see these things in... It looks like we’re not very far above them. It’s fantastic.

Thomas Stafford

Apollo 10 mission timeline

All times are GMT

18 May 16:49 Launch at Pad 39B, Kennedy Space Center.

18 May 19:28 Translunar injection begins.

18 May 19:51 Command module separates from the S-IVB engine. The command module docks with the lunar module.

18 May 19:55 TV coverage of docking procedures transmitted.

22 May 15:51 Cernan and Stafford cross over to the lunar module and activate systems.

22 May 19:00 Lunar module undocks.

22 May 20:35 Lunar module inserted into descent orbit.

22 May 21:30 Lunar module makes closest approach, 15km over the surface.

23 May 03:11 Lunar module redocks with command module.

24 May 10:25 Apollo 10 begins its return trip to Earth.

26 May 16:52Crew splash down in Pacific Ocean and are recovered by USS Princeton.