Mission brief

Launch date: 3 March 1969

Launch location: Launch Complex 39 A

Orbits: 151

Furthest distance from Earth: 497km

Duration: 10 days, 1 hour, 54 seconds

Return date: 13 March 1969

Main goals: Test lunar module; rehearse lunar module docking; rehearse emergency rescue spacewalk

Firsts: Crewed lunar module flight; lunar module docking on orbit; spacewalk on lunar module.

Menu: Shrimp cocktail, beef and vegetables, cinnamon toasted bread cubes (8), date fruitcake, orange-grapefruit drink

The Apollo astronauts knew better than anyone that landing on the Moon was always going to be a formidable challenge.

When the crew of Apollo 9 – Commander James McDivitt and pilots Russell Schweickart and David Scott – blasted into low Earth orbit on 3 March 1969, the G-force pressing down on their bodies was not the only pressure they were under.

Two months earlier, the Soviets had docked two modules in space.

To NASA, this was a clear precursor to a manned lunar landing, despite official Soviet pronouncements that there were no plans to put a Russian on the Moon (in fact, there were at least two Soviet lunar programmes and both were in chaos).

In December 1968, Apollo 8 – the first crewed circumlunar flight – had pulled the US into the lead for the first time since the beginning of the Space Race.

They couldn’t afford to fall behind now.

With the clock running down on meeting the “end of this decade” deadline for a lunar landing set by President John F Kennedy, NASA had lined up a gruelling schedule of five Apollo missions throughout 1969, with the earliest chance of a landing being the third.

If Apollo 9 didn’t go to plan, the whole timeline would be at risk.

And the crew knew it.

There was little room for error, especially as the mission was testing one of the most important parts of the entire project: the lunar module that would carry the moonwalkers to the surface.

In the Saturn V’s launch configuration, the Apollo lunar module was stored behind the command module, where the crew would live for most of the time during missions.

It needed to be extracted from the upper stage before the mission could progress.

Work began on this task as soon as Apollo 9 entered orbit.

After a few hours, the crew undocked the command module, called Gumdrop, from the booster stage before flipping around and docking with their lunar module, named Spider.

After a day of testing the combined spacecraft's manoeuvrability, everything seemed to be going well.

It was only on the third day, as the crew prepared to cross over to the lunar module, that things began to go wrong for the module’s pilot, Schweickart.

Knowing he was susceptible to motion sickness, Schweickart had spent his first two days in orbit holding his head still to prevent himself feeling ill in microgravity.

Unfortunately, in doing so, he’d also stopped his body adapting.

As he suited up to head over to the lunar module, he was forced to bend over while contorting himself into his spacesuit, and motion sickness struck.

Being sick is unpleasant at the best of times, but in microgravity it can be a serious safety hazard.

Schweickart was due to make the first spacewalk of the Apollo programme with commander McDivitt the next day.

If he vomited inside his suit, he would certainly choke.

Spacewalk in jeopardy

The spacewalk was designed to test the manoeuvres needed for astronauts to crawl across the outside of the lunar module to the command module, as they might have to do if there was a problem with docking while returning from the Moon.

It was an important safety test.

Without it, the mission may have to be repeated, pushing back the lunar landing by another two months.

But when Schweickart was ill a second time, Commander James McDivitt had no choice but to cancel the spacewalk.

Thirty years later, the lunar module pilot told NASA historians that night was one of the lowest points in his life.

“I had a real possibility in my mind at the time of being the cause of missing Kennedy’s challenge of going to the Moon and back by the end of the decade,” said Schweickart.

“Getting to sleep is never an easy task in space, but it was particularly difficult that night.”

But sleep he did, and when he woke up Schweickart felt much better.

McDivitt saw the change and, equally feeling the pressure to deliver a successful mission, put the spacewalk back on the schedule at the last minute.

The spacewalk was truncated from two hours down to just 47 minutes, but that still left enough time to test moving around using the handrails on the lunar module’s exterior, proving it would be possible to do so safely.

Cast into space

With spacewalk success achieved, it was time for the lunar module, with McDivitt and Schweickart on board, to go it alone.

The next day, they prepared to detach Spider, and drift away into space.

To the public eye, this seemed an incredibly dangerous prospect.

If there was a problem, the pair could end up stranded.

And Spider’s appearance did little to instil confidence.

During an early visit to the lunar module’s manufacturer, McDivitt ridiculed what he assumed was a test model for being made of “cellophane and tin foil put together with Scotch tape and staples”.

He was horrified to learn it was a flight-ready model.

Though improvements had been made to the module in the years since, several panels had come loose during launch, leaving things in quite a mess.

“I bet you there’s not 50 per cent of the things over there [in Spider] that work,” said McDivitt.

But after months of simulations, the pair were confident in their ability to complete the task.

David Scott aboard the command module released Spider into space.

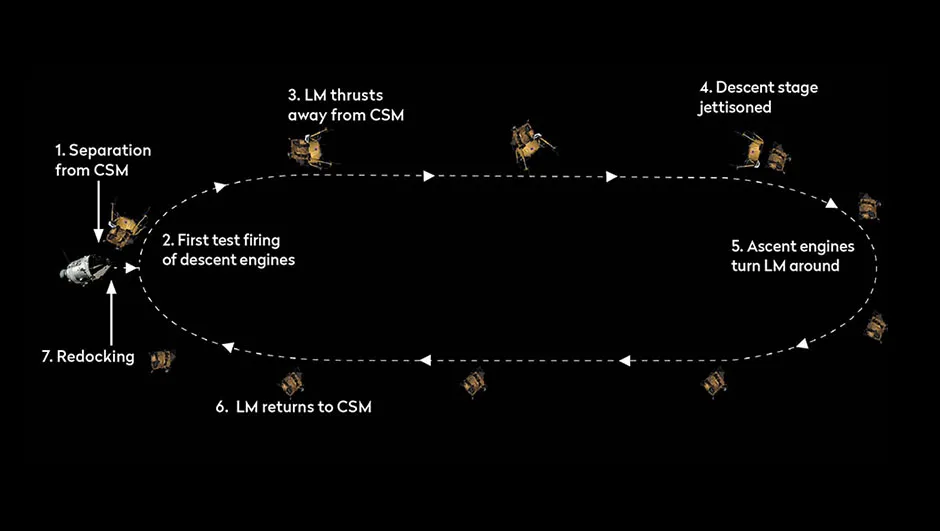

It backed away to a safe distance of around 3km, where Schweickart test fired Spider’s descent engines, designed to gently lower future landers to the Moon’s surface.

Spider was carried 150km away from Gumdrop before jettisoning the descent module, the part that would remain on the lunar surface during landing missions.

McDivitt and Schweickart then test fired the ascent engines, which sent them back to the command module where they safely redocked, establishing that the lunar module worked as expected.

The crew remained in orbit another five days to mimic the time it would take to return from the Moon, keeping busy with systems checks and Earth observations.

While the mission’s main objectives had been achieved, the tight schedule still allowed little chance to eat and sleep.

Indeed, like several other astronauts, lunar travel demanded too much of Commander McDivitt and following Apollo 9 he gave up his dreams of reaching the Moon himself.

Instead, he would help his friends get there, including Scott.

“It was easy to burn out on missions,” Scott said in his biography.

“The great NASA team made them look easy.

They were really, really hard.”

The astronauts

Commander: James McDivitt

Born 10 June 1929, air force pilot McDivitt joined NASA in 1962. After flying the Gemini 4 and Apollo 9 missions, he took over managing the Apollo programme in August 1969, just after Apollo 11.

In 1970 he helped guide the crew of Apollo 13 through the emergency procedures he himself rehearsed during Apollo 9.

Command module pilot: David Scott

Texan Scott, born 6 June 1932, initially dismissed Apollo as a pipe dream.

He joined NASA’s third class of astronauts in 1963 and flew with Neil Armstrong on Gemini 8, a mission which nearly ended in disaster when a stuck thruster sent it spinning. In 1971 he became the seventh person to walk on the Moon.

Lunar module pilot: Russell ‘Rusty’ Schweickart

Born 25 October 1935 in the aptly named Neptune, New Jersey, fighter pilot Schweickart joined NASA in 1963. After Apollo 9, he took part in a study on space sickness before transferring to the Skylab project, but never flew in space again.

In 2002, he co-founded a foundation to raise awareness of the threat of asteroid impacts.

Apollo 9 timeline

3 March 16:00 Apollo 9 launches from Kennedy Space Center.

3 March 18:41 The command module undocks from Saturn V’s booster stage and turns around.

3 March 19:01 The command module docks with, then extracts, the lunar module, Spider.

5 March 11:15 Schweickart and McDivitt cross over into the lunar module. Schweickart begins to suffer from space sickness.

6 March 16:59 Spacewalk starts. Lasts 47 minutes.

7 March 12:39 Spider undocks from the command module. Descent thrusters carry it over 150km away. The module jettisons the descent stage.

7 March 19:02 Over six hours later, Spider uses ascent thrusters to return to and redock with the command module.

13 March 17:00 The return capsule splashes down in the Atlantic Ocean.

23 October 1981 Lunar module descent stage reenters Earth’s atmosphere.

All times are GMT.