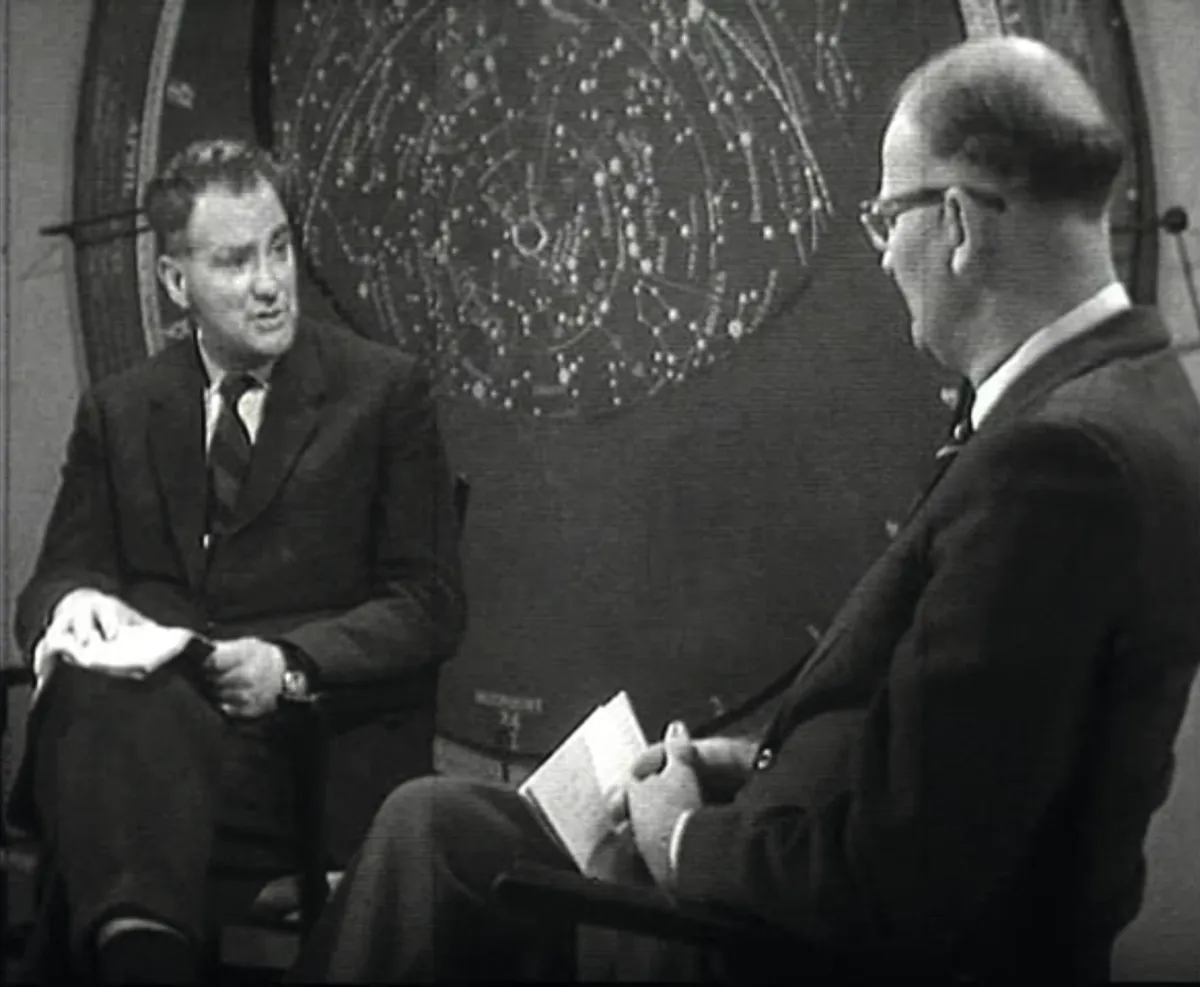

Arthur C Clarke, an old friend, joined me on The Sky at Night in 1963. It was a programme I remember well.

He was a great visionary, remembered today both as a space scientist and as a science-fiction writer – and of course the film 2001: A Space Odyssey, which he co-wrote, will never be forgotten.

The great point about Arthur was that he really believed everything he said and so he was never inclined to compromise: others could disagree and argue with him persuasively but he would seldom change his opinions.

He got a great deal right and I remember on one particular instance he was saying that human beings would reach the Moon by 1990.

I said at the time that 2000 would be a better guess. As we all know, Arthur was right and I was wrong.

Where he did go wrong was in his belief that by 2000 we would have contacted other intelligent beings in the Universe and begun making plans for a true space empire.

This was his main mistake, but no-one could have done better.

I asked him where he thought we would have got in space research by the end of the century. In fact, he turned out to be rather wide of the mark.

He certainly believed that we would be back on the Moon and possibly on the way to Mars.

Well, things have not quite worked out like that.

We have had our successes, notably the International Space Station, and our uncrewed ventures into space have been most productive.

But crewed research has not made the strides he expected. At the time when we reached the Moon I was more confident than I was a few years later

Let us ask ourselves just why things have not gone exactly as planned.

What’s holding humans back in space?

Money

The main problem, of course, has been money. Governments are reluctant to spend large sums of money on ventures that bring no immediate returns – the here and now is always more pressing.

I am afraid that as long as conflicts need fighting and banks need bailing out, we will not get very far in space and we can only hope that things will alter in the foreseeable future.

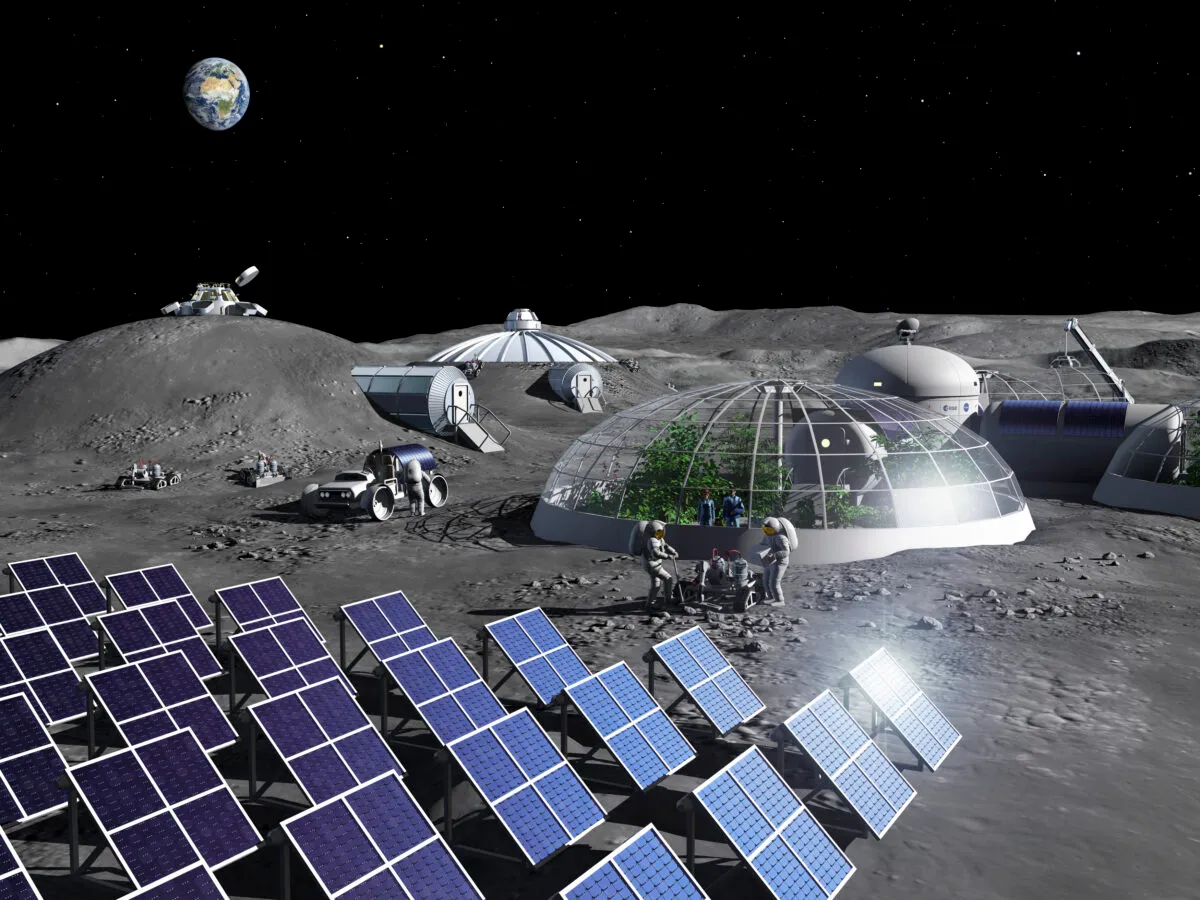

Where could we go after the Moon? We could put up a fully fledged lunar base, which should be of immense value to mankind as a jumping-off point, a weather station and all manner of other things.

Basing ourselves on the Moon would also tell us how effectively human beings work when in space or under feeble gravity for long periods.

There seems no reason to believe that living under weak lunar gravity would have any serious physical effects on human beings, although one cannot be sure until it has actually been tried.

Of course, the main trouble is radiation. On the airless Moon there is nothing to protect space travellers from the harmful radiation that comes in from the Sun and space all the time and as yet we have no way to counter this.

Radiation

Arthur was telling me long ago that we would be on Mars by 2030.

I think quite obviously this was wrong. Going to Mars means being in space, unprotected, for several months, and no human being could tolerate the radiation absorbed in that time.

On the Moon we can construct safe areas into which astronauts can retire in times of danger and we have now learnt to predict these dangerous periods pretty well.

But on a spacecraft on the way to Mars, where weight is at a premium, there are no boltholes in which to hide.

So from this point of view, we must do some very hard thinking.

It would be wrong to say that we have any idea of how to tackle the radiation problem; we have not and we have to admit we do not have the faintest idea where to begin.

I am sure the breakthrough will come one day and that the radiation problem will be conquered as efficiently as all the other problems have been.

At the moment, we are still waiting on that one.

Lack of international cooperation

But now let me turn to what is probably the most critical problem of all.

There was a time when space research was limited entirely to Russia and America, and it was only later that the other nations joined in.

Before a final programme we must have full international agreement and full collaboration in all branches of scientific research.

As of yet we do not have this and behind all science is the lurking threat of new discoveries being used for warfare.

It is essential to change this, if we are ever going to make much progress in space.

There is of course an answer and that is to persuade the voters in all nations to opt for peace and progress instead of suspicion.

But that day has not yet arrived and when it will do so remains to be seen.

Reflections on human spaceflight

If Arthur had been able to look forward to the year 2012, I think he would have been disappointed.

Crewed space research has simply not gone as smoothly as he would have hoped.

We have had the Space Shuttle programme, which achieved a great deal but has now come to a rather inglorious end.

As I write these words, the only way to get material to and from the ISS is to enlist the aid of the Russians (Ed: I wonder what Patrick would have made of the current era of private spaceflight companies?).

And there have been problems with the Soyuz rocket on recent missions.

I am no Arthur C Clarke, but I have my own ideas about what might happen within the next few decades.

Come with me to the year 2090. Will there be more international space stations or will we concentrate on a proper base on the Moon?

I would have done the latter from the outset – I was never a real enthusiast for a space station, which has not yet achieved a great deal.

So I believe that the main feature of the next 50 years should be the development and perfection of a lunar base.

Some of those who read this may still be alive then and will be able to judge whether my predictions are right or wrong. I would very much like to know…

But by then, I will be a figure of the remote past!

This article originally appeared in the February 2012 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.