Soviet Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first human being to travel into space when he blasted off from Baikonur Cosmodrome in a Vostok-1 rocket on 12 April 1961 at 09:07 Moscow time, circling the Earth for 108 minutes before landing back on the ground safely.

But who was Yuri Gagarin, and what was the chain of events that led up to his monumental spaceflight at the height of the Cold War?

By 1961, less than 4 years after it had launched the first artificial satellite Sputnik 1, the Soviet Union was locked in a tense race to outdo the US in terms of spaceflight achievements.

Largely as a result of the work of visionary Russian rocket engineer Sergei Korolev, the Soviets had bagged every major milestone to this point: the first artificial satellite in Sputnik 1, the first animal in space, the first lunar impact.

But they knew that if they could launch a human before the US, it would cement their reputation as the space superpower.

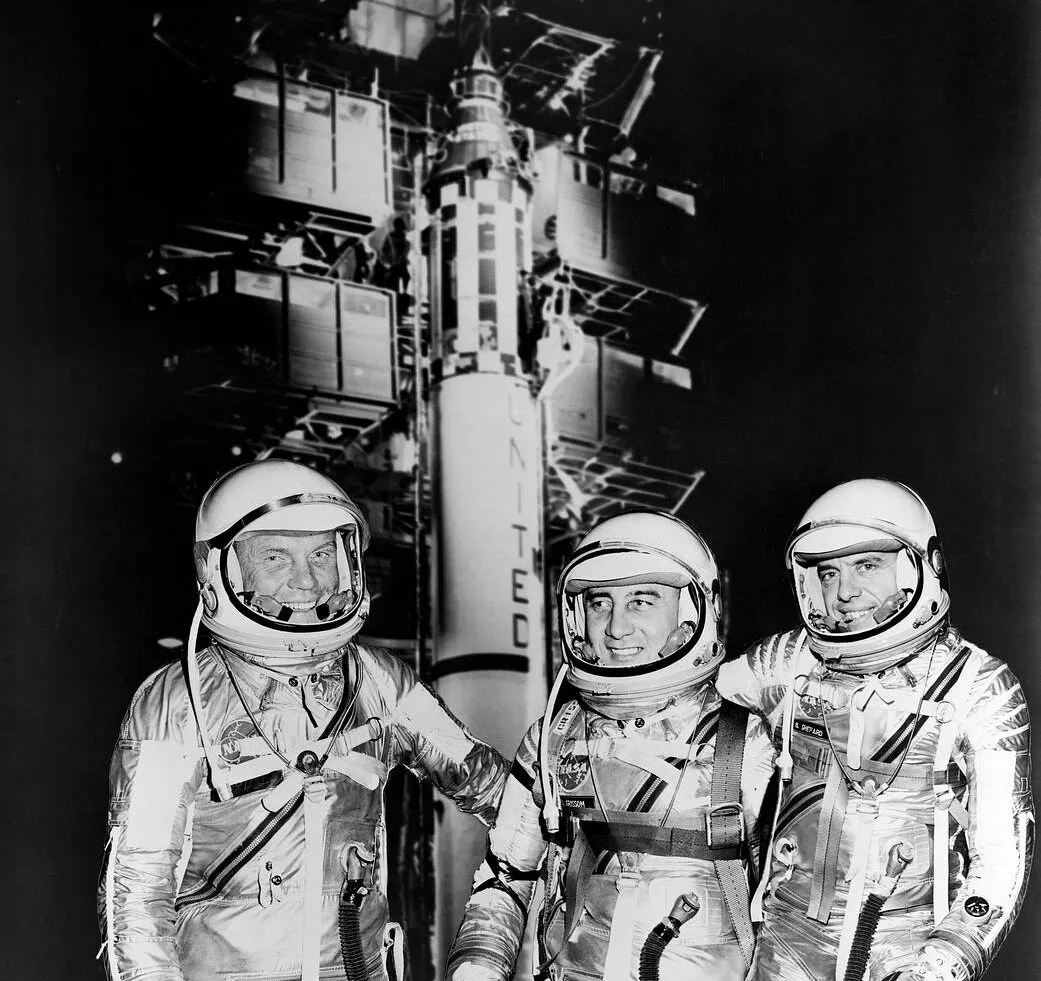

It was the most closely run leg of the entire Space Race. Though the Soviets gave away little in public, the US were ensuring the entire world knew that their Mercury 7 astronaut Alan Shephard was on course to triumph over their Space Race competitors and become the first human being in space.

On 12 April 1961, Shepard’s flight was just 3 short weeks away when the announcement sounded out across the Soviet Union Yuri Gagarin had beaten him to it.Gagarin was a Soviet hero and, taken unawares, the US was humiliated.

Those initial announcements depicted a flight entirely without flaw: a perfect victory over the US. In fact, the flight had almost been a disaster several times over.

Over the subsequent decades, the truth of what happened has slowly emerged and in 2011, on the 50th anniversary of the flight, the Russian government released hundreds of official documents about the mission.

Yuri Gagarin: a short biography

He is now known as the first human being to travel into space, but who was Yuri Gagarin?

Yuri Gagarin was born on 9 March 1934 on a collective farm in the village of Klushino, 200km west of Moscow in the Smolensk Oblast province.

Yuri Gagarin’s fascination with flying machines began at an early age. He spent many of his school days building model aircraft and learning about the Soviet air heroes of the Second World War.

At 16, he was employed by the local foundry and quickly earned himself a place at a technical school in Saratov, where he joined a local flying club.

By 1955, he was enrolled at the Air Force’s pilot school where he met and married Valentina Goryacheva. The couple went on to have two daughters.

By 1959, Gagarin was secretly selected for the first ever class of cosmonauts, where he proved himself capable and popular.

When the Vostok-1 mission was being selected, he was a clear frontrunner alongside his colleague Gherman Titov. In the end, Gagarin’s rise from a farm to a foundry to the stars was seen as the best embodiment of Soviet ideals.

After his historic flight, governments around the world invited Yuri Gagarin to visit – but not the UK.

The cabinet of the day feared upsetting their US allies, so instead it was the trade unions who took it upon themselves to invite the Soviet hero to visit from 11 to 15 July 1961.For more on this piece of spaceflight history, read the full story of Yuri Gagarin's visit to the UK.

Though Gagarin was initially kept on as a cosmonaut by the Soviet space programme, when the first flight of the new Soyuz craft resulted in its pilot’s death, Gagarin was deemed too valuable an asset. He was banned from spaceflight permanently.

But despite this precaution, on 27 March 1968 Gagarin was killed when the MiG-15UTI fighter jet he was flying crashed during a training exercise.

Today, dozens of streets and towns bear his name, while monuments to him can be found worldwide, commemorating the man who rose from the Earth to reach the stars.

The day of Yuri Gagarin's flight

Yuri Gagarin's Vostok 1 mission that made him the first human being in space was almost cancelled before it began.

During a last-minute weigh-in the night before the flight, the ground crew realised that the combined weight of Gagarin, his spacesuit and his seat were 13kg over the limit.

The engineers worked through the night to remove every piece of equipment that didn’t need to be there and fix any damage they created along the way.

Meanwhile, Gagarin and his back up Gherman Titov were having a much more relaxing time. They were under strict instructions not to discuss the coming mission and instead spent the night playing pool and chatting about their lives before becoming cosmonauts.

Both were sent to bed at 9:30pm, but apprehension about the coming day meant neither managed to sleep that night.

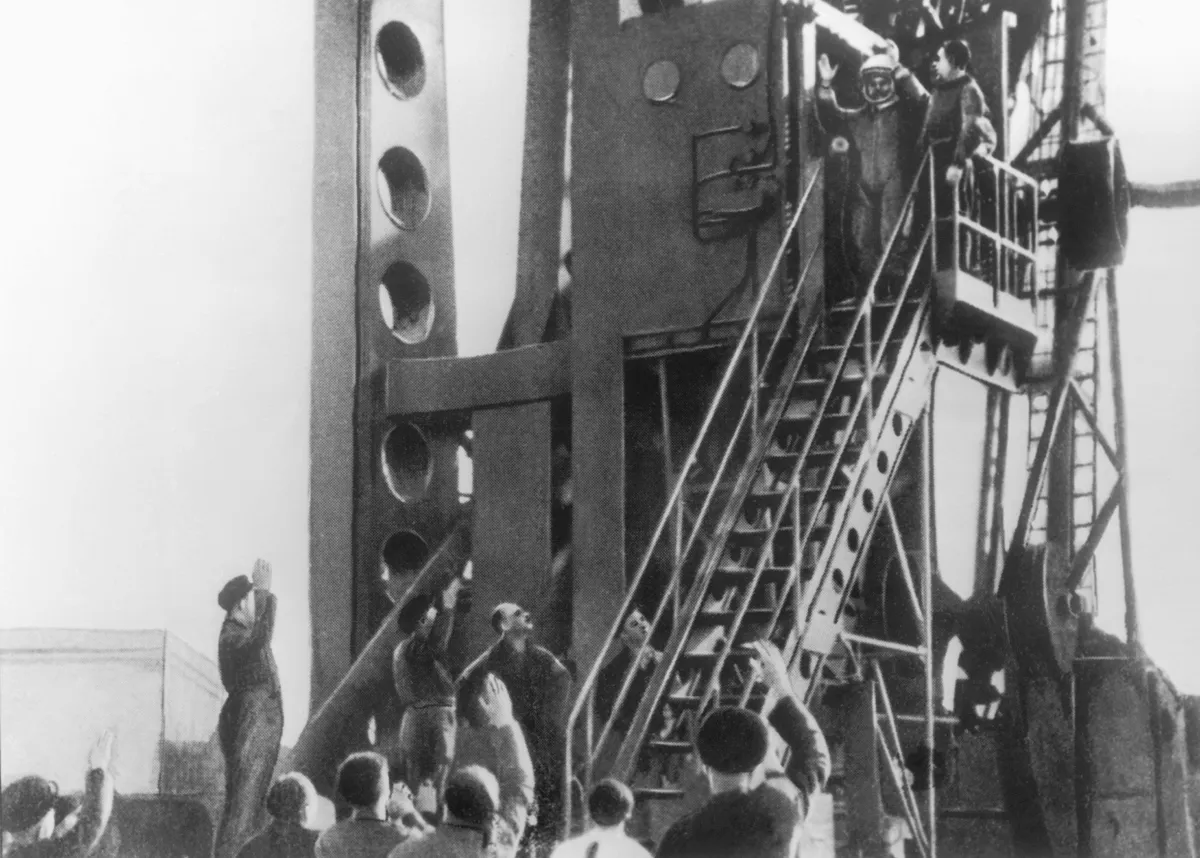

Gagarin was roused at 5:30am and gifted with a bunch of tulips from a local woman’s garden.

He didn’t shave – it was considered bad luck by Soviet pilots – but instead ate a breakfast of tubed food, similar to those he’d be trialling later during the flight.

Afterwards, Gagarin donned his newly lightened spacesuit and boarded the special bus to take him to the launch pad.On the horizon, the 30m-tall rocket rose up, a shining spire of silver against the background blue of the sky.

"The closer we got to the launching pad, the larger the rocket grew, just as if it were changing size," Gagarin would later recall in his autobiography, Road to the Stars. "It looked like a giant beacon and the first ray of the rising Sun shone on its pointed peak."

Gagarin was swiftly loaded into his Vostok capsule before the technicians began hermetically sealing him away from the world, ready for launch. Only, the door wouldn’t shut.

Feeling of weightlessness is interesting. Everything floats. Floating is everything. Wonderful! Interesting.

Yuri Gagarin during the Vostok 1 flight

The crew set about hastily unscrewing panels to reach the problem, managing to fix it with enough time to make the launch. Meanwhile, Gagarin joked with his colleagues over the radio and sang to himself.

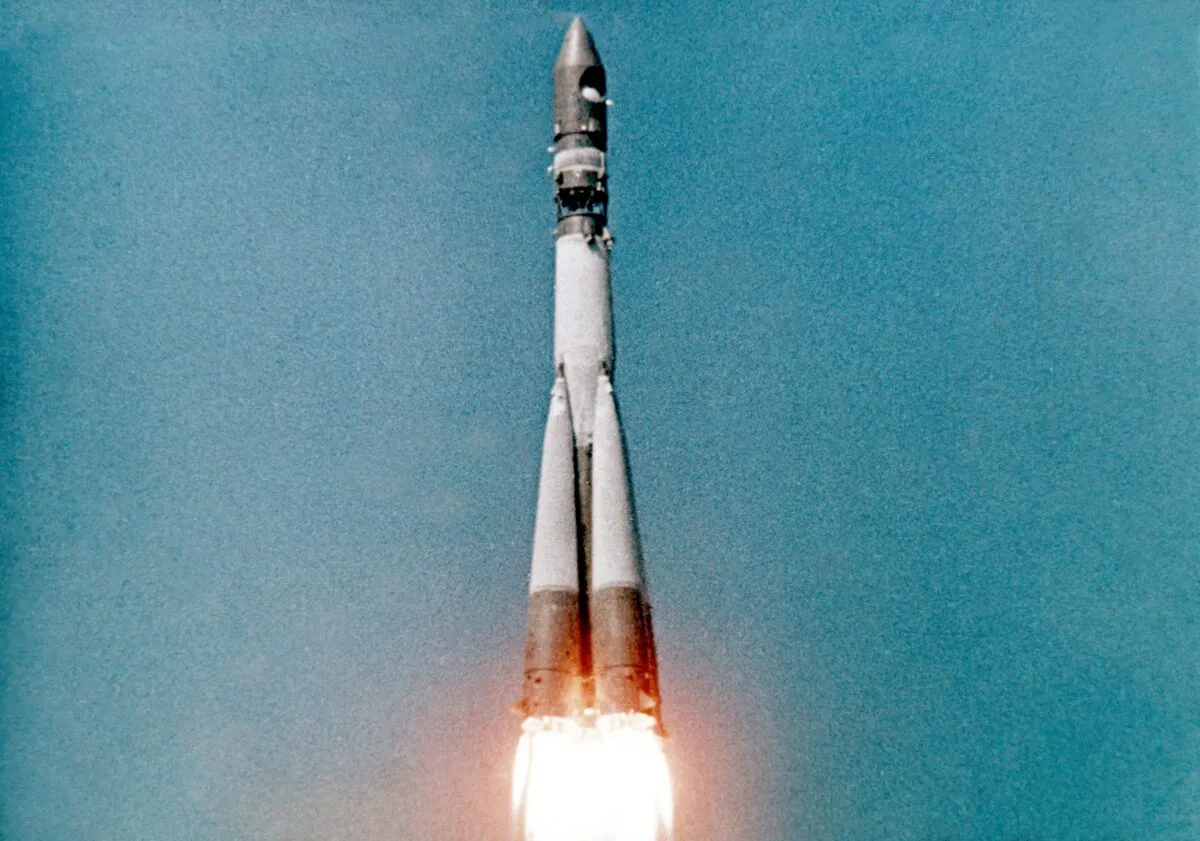

Soon enough, it was time to prepare for launch. Two minutes before launch Gagarin began to feel the rocket sway and move as it readied itself before, at 9:07am Moscow Time, the engines of the R7 roared into life.

Inside the capsule, Gagarin let out a victorious yell of "Poyekhali! [Translation: 'Let’s go!'] Goodbye until we meet soon, dear friends."

As the rocket rose through the air, Gagarin was subjected to intense g-forces, his heart rate rising to 150 bpm.

The intense conditions of launch obscured the radio signal, while the g-forces made it difficult for him to speak.

For one agonising minute, the technicians could do nothing but wait for the signal to return and let them know that their colleague was still safe, racing upwards on his journey towards the stars.

When Gagarin’s voice did come back on the air, however, it was free of apprehension. "I see Earth," he said, the first time human eyes had seen such a view. "I see the clouds. It’s beautiful. What beauty!"

As he continued to rise, he reported back his "buoyant mood" and how smoothly the flight was going. A little too smoothly, it would turn out.

The engines failed to cut out when they were meant to and Gagarin ended up overshooting the intended altitude of 230km, instead reaching 327km.

Meanwhile, the Soviet media machine was beginning to swing into operation, announcing that the mission had launched flawlessly and was on course for success.

In orbit, Gagarin got to work – though this wasn’t to include actually piloting the spacecraft. Despite being a highly qualified pilot, Soviet psychologists feared that the experience of weightlessness and seeing Earth from above would completely unravel the human mind.

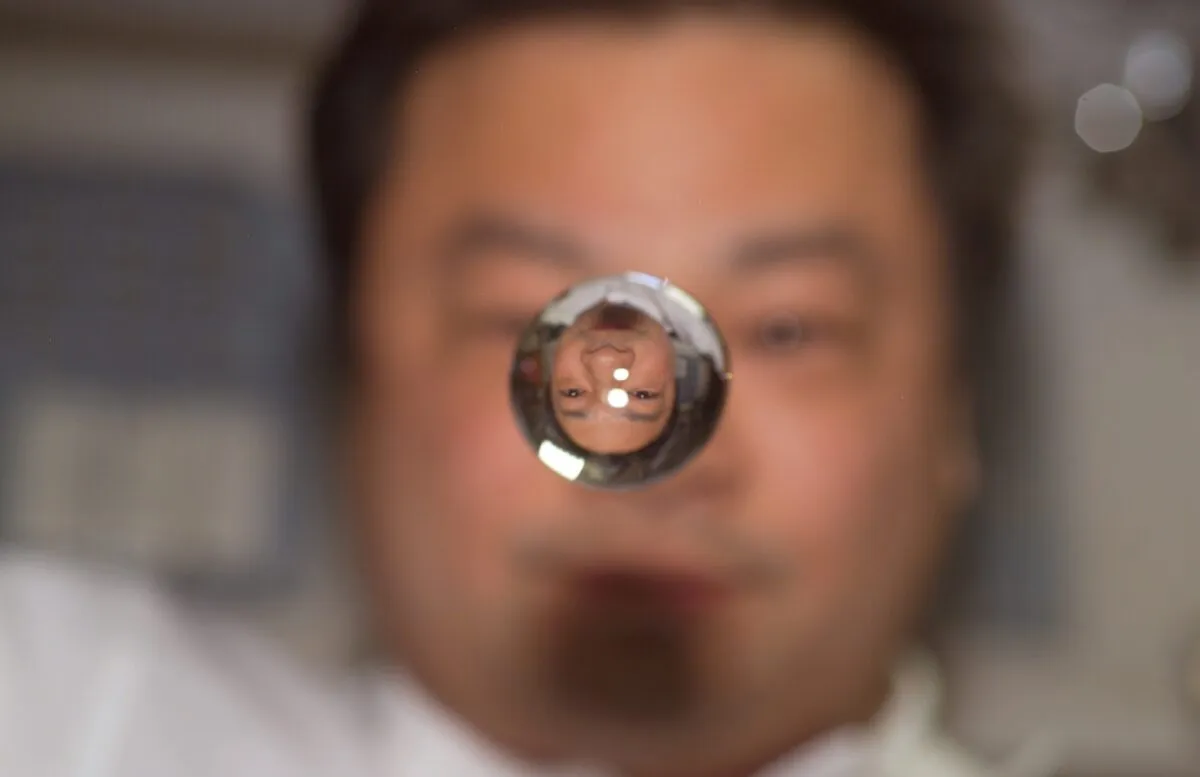

A drop of water escaped and Gagarin took a few moments to marvel at the perfect sphere suspended in the air

Believing that Gagarin could be mentally incapacitated and crash the spacecraft, he’d been locked out of the controls.

The spacecraft did carry an envelope with a code to release the controls but it was only supposed to be opened in an emergency – a fact that didn’t sit well with several of the ground staff, who had secretly told Gagarin the code in the run-up to launch.

Gagarin didn’t lose his wits, however. Instead, he easily acclimatised to the strange experience and seemed to be quite enjoying himself.

"Feeling of weightlessness is interesting," he said during the flight. "Everything floats. Floating is everything. Wonderful! Interesting."

With Earth’s gravity falling away, Gagarin found himself able to move about more easily than he could on Earth.

Between making notes in his logbook, he would let his writing pad and attached pencil float in front of him, marvelling at how they were suspended in microgravity.

When he caught it to make his next report, however, he found the pad but not the pencil. It had become untethered and floated off, never to be seen again.

Unable to make notes, he moved onto trialling the food and water tubes that his fellow cosmonauts would need on longer missions.

While proving that he could consume these without Earth’s gravity, a drop of water escaped from the water tube and Gagarin took a few moments to marvel at the perfect sphere of water, suspended in the air.

Back on Earth, the US has had picked up the signal of Gagarin as he passed overhead. While the CIA prepared a report for President Kennedy, NASA broke the news to Alan Shepard that he wouldn’t be the first human to reach space.

Gagarin’s flight was only ever intended as a short test. After 78 minutes, the spacecraft prepared to return to Earth – a stage that, unbeknownst to Gagarin, had become far more perilous than initially planned.

The flight path had been designed so that the atmospheric drag would naturally deorbit the spacecraft, and there was 10 days’ worth of food, water and air so that Gagarin would be able to survive the wait.

However, because the Vostok had overshot its intended altitude to a height where the air was much thinner, it would now take 20 days to return.

As there was nothing to be done but hope the engines worked, the cosmonaut wasn’t told of his predicament.

With no idea of the risk, Gagarin closed his helmet, secured his seat straps and waited for the engines to fire. To the relief of everyone on the ground, they did.

For 42 seconds, Gagarin felt the spacecraft slowing, only for the deceleration to end with a sudden jolt. His descent module had separated from the instrument module as expected, but the tether connecting them had failed to release.

The unwieldy straggler was causing the capsule to spin out of control. The Sun flashed through the windows, dazzling Gagarin, while the g-forces caused his vision to go grey as blood was forced from his brain.

Despite this, Gagarin remained calm, reporting his situation back to the ground.

For 10 minutes the temperature climbed rapidly, threatening to incinerate the pod until there was a final bang – the tether had burned through.

The instrument module shot off, as the descent module righted itself into its correct orientation. The hatch opened, Yuri Gagarin ejected about 7km above Earth's surface and parachuted to safety.

Beneath him, Gagarin could see the silver line of the Volga River winding through the Saratov region of Russia – the very place he’d learned to fly years before

It was 108 minutes after blast-off when Gagarin’s feet touched back down onto Earth.

As he opened up his helmet to take a deep breath of terrestrial air, he spotted a woman, her granddaughter and their spotted calf watching him in confusion.

"Have you come from space?" the woman asked. "As a matter of fact, I have," he replied, as a group of nearby farm workers ran towards him, crying out his name.

Just over an hour later, the radio proudly announced his return to "the sacred soil of our motherland".

But the vision these early broadcasts conjured was very different to the flight Gagarin had just experienced. In the ‘official’ version, the cosmonaut hadn’t ejected, but landed in the Vostok – a necessary requirement to claim the achievement under international aviation regulations.

He’d also apparently landed bang on target, rather than 300km off-course, as actually happened.

Though the precise details of the story might have changed over the last 60 years, there is one thing that remains undeniable. Yuri Gagarin launched as just another citizen and returned as a hero.

Timeline: Yuri Gagarin's flight

All times in Moscow Time (UTC +3)

- 5:30amYuri Gagarin and Gherman Titov wake up, eat breakfast and put on their space suits.

- 5:45am The cosmonauts board the transport bus and drive to the launch site.

- 6:50am The bus reaches the launchpad. A worker writes CCCP on Gagarin’s helmet so he isn’t mistaken for an enemy pilot on his return to Earth.

- 7:07am Gagarin boards Vostok-1.

- 9:07am Lift-off. After a few minutes the g-forces prevent Gagarin from speaking.

- 9:12am Radio contact resumes.

- 10:02am Radio Moscow announces the launch.

- 10:25am Vostok-1 returns to the atmosphere. Shortly after, the instrument module fails to detach fully, sending the descent module into a spin.

- 10:35am The craft stabilises after the connecting cord burns through.

- 10:49am Gagarin ejects at 7km altitude and begins parachuting to the ground.

- 10:55am The spacecraft lands, slowed by its own parachute.

- 10:57amGagarin lands 3km from the spacecraft and is greeted by the local workers.

Dr Ezzy Pearson is BBC Sky at Night Magazine’s news editor and author of Robots in Space. This article originally appeared in the April 2021 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.