On 12 April 1961 Yuri Gagarin became the first human being in space. Today it seems unlikely that this cosmonaut celebrity would visit an engineering factory in Manchester, having made a trip to London.

But Yuri Gagarin visited England from 11-15 July 1961, and thousands of ordinary people turned out to see him during his stay.

The government of Harold Macmillan had been unwilling to extend an official invitation to the West’s then sworn enemy, the Soviet Union. Both East and West had nuclear weapons aimed at the other and the Berlin Wall was just weeks from being built.

More Soviet spaceflight:

- Alexei Leonov, the first person to spacewalk

- Gallery: 10 Soviet space posters of the Cold War

- History of the Soyuz rocket

How could Britain celebrate Soviet achievements in space when America’s own efforts – at that point – paled in comparison?

Politically acceptable compromises eventually allowed a visit that tied in with the Soviet Trade Exhibition at Earl’s Court in London.

But when Gagarin arrived, he received a welcome equivalent to that of a movie icon.

Such was the excitement among the press and public after his spaceflight that the government had to move quickly and extend his stay to include engagements with the Queen at Buckingham Palace and with Prime Minister Macmillan in Whitehall.

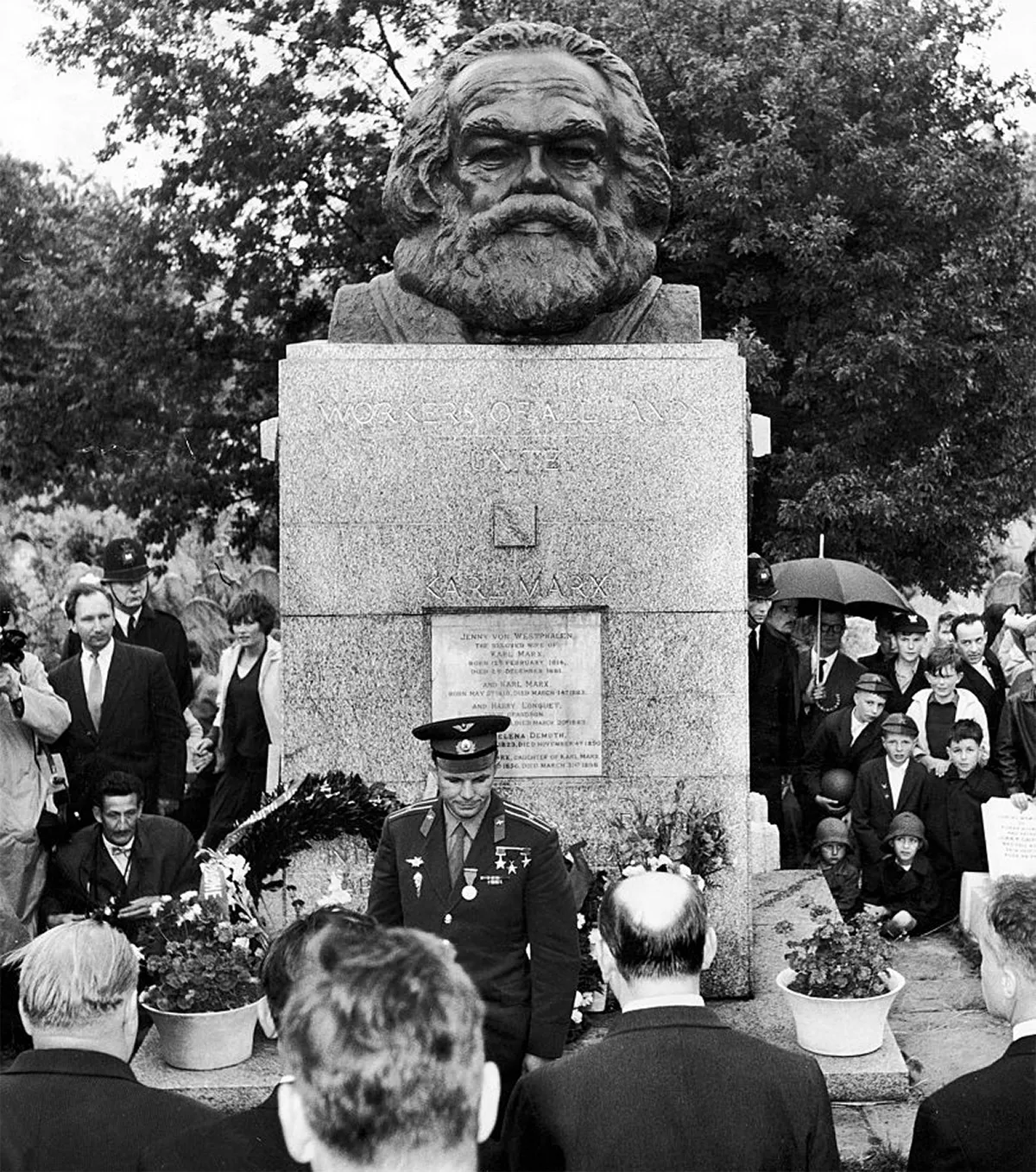

In addition, there was a wreath-laying at the Cenotaph and an officially sanctioned visit to the Air Ministry, as well as trips to sites of note to Soviet people, such as Highgate Cemetery – the resting place of Karl Marx.

Gagarin visits union workers in Manchester

But this trip wasn’t just about meeting officials of state. On 12 July 1961, Gagarin flew up to Manchester as a guest of the Amalgamated Union of Foundry Workers, who invited him to the Metropolitan-Vickers (also known as AEI) engineering plant in Trafford Park, the city’s industrial hub at that time.

Before he was an airman and a cosmonaut, Gagarin had been eager to learn a profession to support his family and trained as an apprentice foundry worker at the Lyubertsy Steel Plant in Moscow.

It was this path that led directly to him becoming a pilot. At Lyubertsy, Gagarin was selected to train at a technical school in the port city of Saratov.

Within hours of his arrival he spotted a notice about the local flying club, where he would realise his childhood dream of becoming an aviator.

The day of his visit to Manchester was, perhaps unsurprisingly, a rainy one. Ever a man of the people, when he saw that the crowds lining the streets to see him were getting wet, Gagarin insisted on lowering the roof of the convertible Rolls-Royce in which he travelled.

"Surely the least I can do is get wet too," he said.

One of the people who got to see Gagarin that day was Tricia Paton, then 24 years old, who recalls: "It was such an exciting moment, it seemed unreal. He had such dignity and good looks. Back then we hadn’t ever seen a Russian, never mind a spaceman."

If the Soviet Union were to combine its efforts with the West, we could make even faster progress in the exploration of outer space and could add even greater achievements to our credit.

Yuri Gagarin

Another, Valerie Clarke, was a schoolgirl at the time: "I was struck by his broad-shouldered military coat which was bright with brass, even on a rainy Manchester day. We children couldn’t escape the feeling of awe at the importance of this man who had orbited our planet."

From Metropolitan-Vickers, Gagarin went on to a civic reception at Manchester’s town hall where the communist hammer and sickle flew over the city and the Soviet anthem was played.

Gagarin’s words at the reception presaged the co-operation we see today with work on the International Space Station.

Through his interpreter, he told the waiting media: "I think that if the Soviet Union were to combine its efforts with the West, we could make even faster progress in the exploration of outer space and could add even greater achievements to our credit."

Gagarin made a lasting impression on the British people and even influenced the careers of some, such as British space scientist Prof John Zarnecki.

"There I was on 14 July 1961, a London schoolboy, standing in Highgate Cemetery, just a few feet away from Yuri Gagarin who was there to pay homage at Karl Marx’s grave," recalls Zarnecki.

"I remember being overwhelmed at the thought that this man had spent 100 minutes in space! If there was a day that changed my life, that was as close as it came."

On a later anniversary of his spaceflight, Gagarin recalled his visit to Manchester during an interview on Radio Moscow: "The firm handshakes of my fellow workers meant more to me than many awards. Inscribed on the medal which you gave to me are the words 'Together we shall mould a better world'.

"This expresses my own feelings and those of everyone in the Soviet Union."