Sitting between Mars and Jupiter is the asteroid belt, a mess of stony, metallic rubble left over from the formation of the Solar System.

From fragments just a few metres wide up to 940km-diameter giant Ceres (classed as a dwarf planet), the millions of objects in the asteroid belt include thousands whose orbit around the Sun brings them into our neighbourhood.

In fact, NASA’s latest estimate puts the number of large near-Earth asteroids at over 28,000.

As these objects have largely remained unchanged over millennia, finding out their size, shape, mass and density, understanding their chemical composition and what their surfaces are like, all give us a crucial window into the earliest days of our Solar System.

It could also help us understand their role in carrying the ingredients for life and, more dramatically, plan how to deflect asteroids on a collision course with Earth.

What makes 433 Eros special?

It was 433 Eros – the first asteroid that humanity landed on – that gave us our first major answers to some of the most fundamental questions about the Universe.

Roughly 33 x 13 x 13km in size and resembling a flattened and dented kidney, 433 Eros orbits the Sun every 643 days, with a path that brings it as close as 22 million kilometres from Earth.

For an interactive 3D view of what it looks like, take a look at this NASA page.

The first near-Earth asteroid to be discovered, back in 1898 by German astronomer Carl Gustav Witt, in subsequent decades 433 Eros remained the most constantly studied by ground-based observers.

This is principally because its predictable orbit helped refine our estimates of how far Earth is from the Sun.

NEAR Shoemaker meets Eros

The Galileo spacecraft's flyby observations of asteroids 951 Gaspra and 243 Ida in the early 1990s got the first peek at two asteroids up close.

But it was NASA’s NEAR (Near-Earth Asteroid Rendezvous) probe – later renamed NEAR Shoemaker – that took asteroid research a huge step forward.

On board were a near-infrared spectrometer to determine Eros’s composition, a multispectral imager, a telescope with a CCD array to determine its size, shape and spin and a magnetometer to measure Eros’s magnetic field.

After a few worrying malfunctions, Shoemaker’s first flyby of 433 Eros was on 23 December 1998 at a speed of 0.965 km/s and a distance of 3827km, after which followed months of close observations.

Fittingly, for an asteroid named after the Greek god of love, it was on Valentine’s Day 2000 that Shoemaker fell into orbit around the asteroid, the first ever spacecraft to do so.

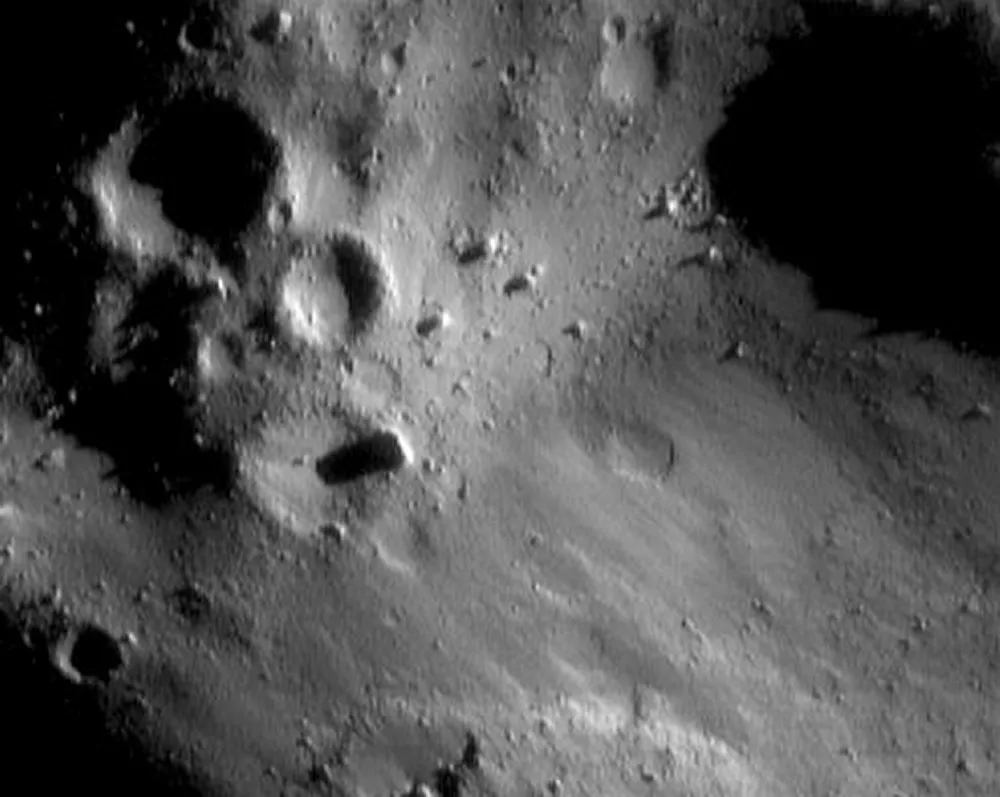

Descending at times as low as just 5.3km above the surface, it continued to capture thousands of high-resolution close-up photographs.

What NEAR Shoemaker found out

After nearly a year and 230 orbits, on 12 February 2001 Shoemaker gently touched down, travelling at just 6.4km/hr, on the asteroid’s eastern side, next to the large saddle-shaped depression called Himeros.

For about two weeks the probe continued to return data, but by 28 February all radio communication was lost.

During its mission Shoemaker had taken 160,000 photographs and mapped the mineral composition of more than 70% of Eros’s surface.

It discovered that the asteroid had just two medium-sized craters, suggesting its relative youth, and a 20km-long surface ridge.

Radar revealed a mix of both smooth and rough areas, with ridges, grooves and depressions, its two craters strewn with boulders, some a whopping 100m in diameter.

It had large variations in brightness in its bouldery surface, with high concentrations of silicon, magnesium, iron, uranium, thorium and potassium.

Its rotation was timed at once every 5.27 hours and it was found to have no discernible moons and no magnetic field.

Radio science experiments showed the asteroid’s mass, a vital clue to the nature of its interior, and a density similar to Earth’s own crust.

Shoemaker also provided indisputable proof that small asteroids could have a substantial regolith, a loose rocky and dusty surface layer hinting at the impacts and erosion in its past.

By the mission’s end NEAR Shoemaker had revealed a treasure trove of physical and geological clues about one of the leftover building blocks of our planets.

When is Eros’s next close approach to Earth?

Eros’s next closest approach to Earth will happen on 24 January 2056, when it will be at a distance of 0.14979957 Astronomical Units or 22.4 million kilometres.

Missions similar to NEAR Shoemaker at asteroid Eros

- In 2005, 25143 Itokawa was the first asteroid to be the target of asample return mission. The Japanese space probeHayabusa collected more than 1,500regolithdust particles from the asteroid’s surface.

- Also in 2005, NASA’s Deep Impact mission fired an impactor into comet 9P/Tempel.

- On 12 November 2014, ESA’s Rosetta craft sent its lander Philae to the surface of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

- In June 2018, Japan’s Hayabusa 2 rendezvoused with asteroid162173 Ryugu, returning its samples to Earth in December 2020. It now plans to land on small asteroid1998 KY in 2031.

- In October 2020, OSIRIS-REx successfully took extensive surface samples of rocks and dust from asteroid 101955 Bennu. These are due to be returned to Earth on 24 September 2023.

- In October 2021, NASA’s Lucy mission launched, the first spacecraft to explore the Trojan asteroids, primitive asteroids orbiting in tandem with Jupiter.

- In November 2021, NASA launched its DART mission (Double Asteroid Redirection Test), the first-ever mission to attempt to deflect an asteroid through kinetic impact. Its target is Didymos and its moonlet Dimorphos.

- Slated for launch in 2022 is NASA’s NEA Scout mission which plans to send a small lightweight Cubesat to encounter near-Earth asteroids, most likely starting with 1991 VG.

Did you know?

Months before NEAR-Shoemaker landed on Eros, Gregory Nemitz of Twin Falls, Idaho, sued NASA, claiming ownership of 433 Eros.

In an attempt to establish whether individuals could claim property rights over celestial bodies, he issued the agency with a parking ticket for $20.