Simply put, a comet is a large body of ice and dust orbiting the Sun, sometimes seen as a bright object in the sky with a long tail streaming behind it.

Wanderers of the Solar System, comets can rank among the most spectacular of astronomical sights when they appear in our skies.

Comets never fail to capture imaginations when they pass by Earth, and after years of observations astronomers have coaxed out the secrets hidden by their glow.

The heart of a comet is its nucleus, a core of ice laced with rock and dust, a few kilometres wide.

Though sometimes called a ‘dirty snowball’, the ice found on comets is far more exotic than that on Earth.

Find out which comets and asteroids are visible tonight or discover our pick of history's greatest comets.

And find out which comets are best this year in our guide to comets in 2024

When the Rosetta spacecraft reached 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko in 2014 it performed the first in-situ analysis of a comet’s nucleus.

It found not only water-ice, but also carbon dioxide and monoxide, as well as traces of ammonia, methane and methanol. It found the ingredients for life.

These highly volatile compounds are usually found as a gas or liquid on Earth, but the frigid depths of space have frozen them to ice as hard as rock.

Comets' orbits explained

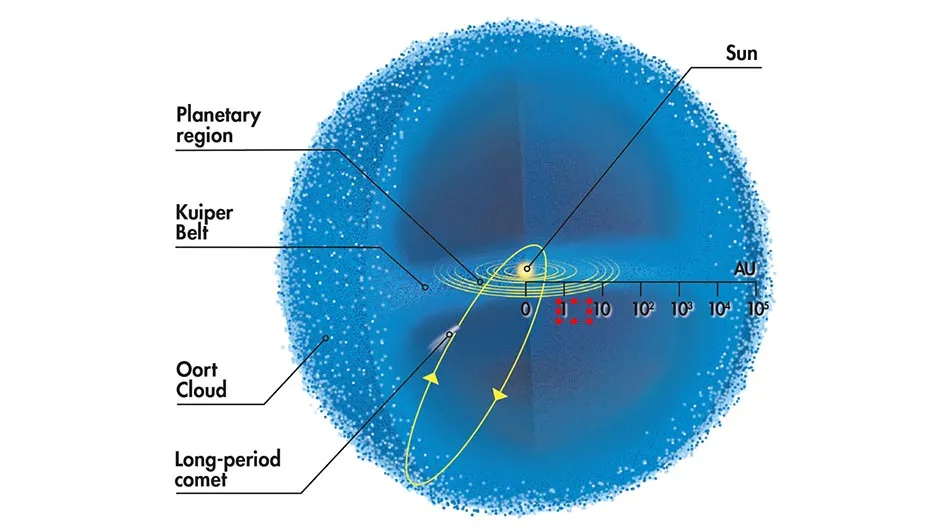

Comets travel in huge elliptical orbits, briefly visiting the inner Solar System at one end before travelling billions of kilometres to the outer regions.

Some, such as Halley’s Comet, have an orbit that only lasts a few years or decades, and are called short-period comets.

Long-period comets travel farther into deep space, taking thousands of years to complete an orbit.

What happens when a comet gets close to the Sun?

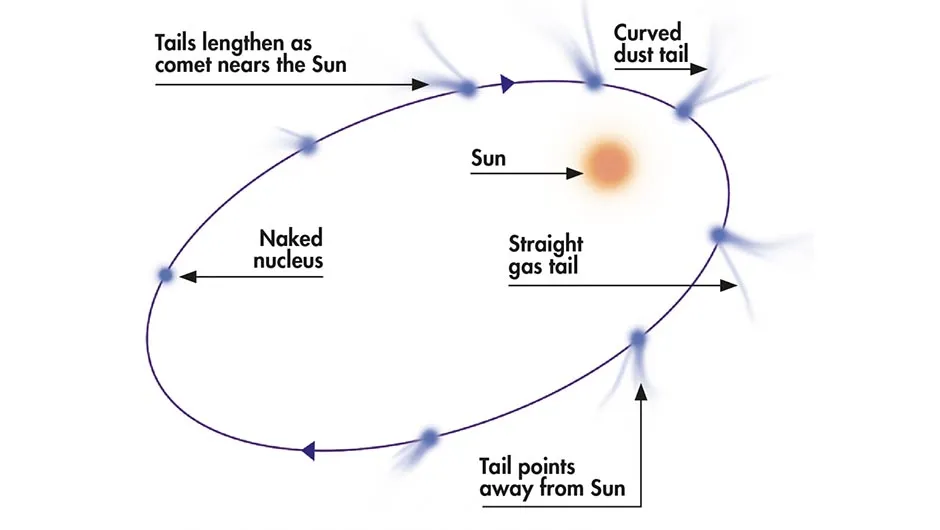

For most of a comets' orbit, the nucleus remains an inert lump of ice, but this changes as the comet nears perihelion, its closest approach to the Sun.

When close enough, solar radiation heats the surface, causing the volatile components to boil.

As the gas escapes into space it lifts off dust, creating a shroud that can stretch out over 50,000km around it, known as the coma.

As the comet gets closer to the Sun, this envelope begins to feel the solar influence even more acutely, as its wind and magnetic field sweep the dust and gas out into a huge tail.

This can extend for millions of kilometres, spanning huge swathes of the Solar System.

Some of the tail’s debris is left behind in its orbit to form a meteoroid stream.

Several of these cross the Earth’s orbit, and when we pass through them every year, we see the debris burning up in the atmosphere as a meteor shower.

For more info on this, read our beginner's guide to meteor showers.

For most comets, these close encounters with the Sun do little more harm than melting another layer off the nucleus.

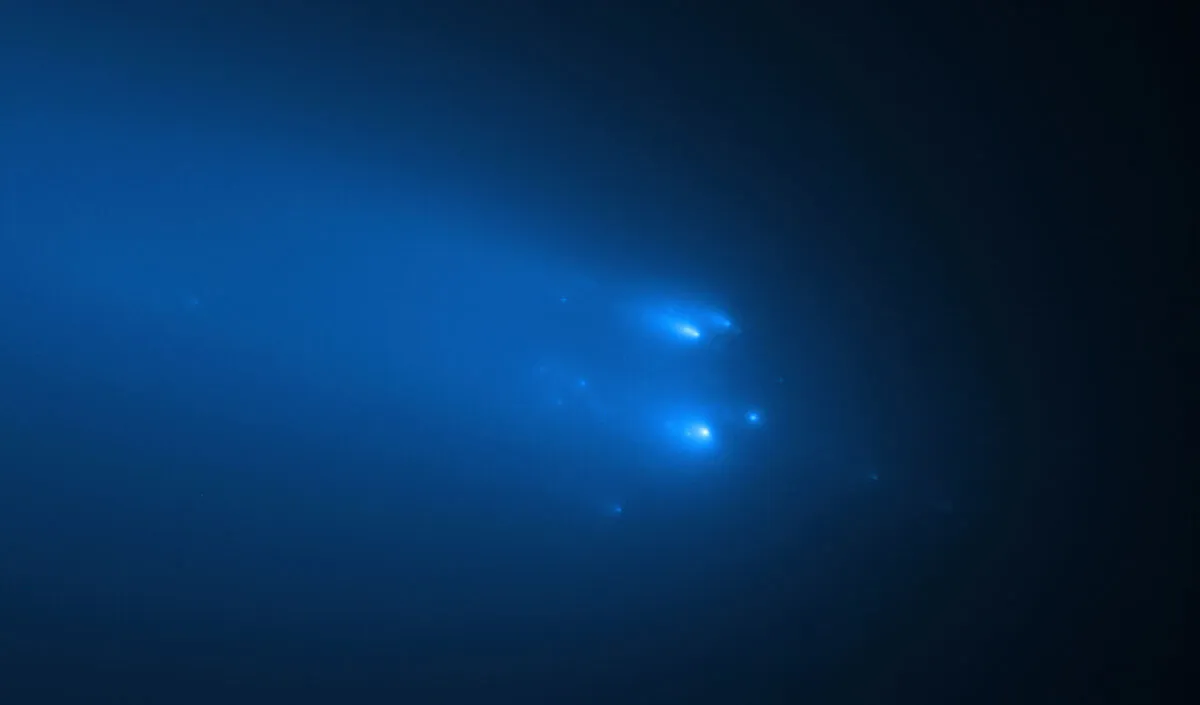

Sometimes comets get too close, and the intense heat and gravity cause them to break apart, as happened in 2013 with C/2012 S1 ISON.

Sunlight reflecting off the coma and tail causes these celestial visitors to glow, making them a popular target for astronomers.

Observing comets

Unlike meteor showers, comets are a more transient phenomena adhering to a timetable all of their own.

Every year there are a handful of comets that can be seen with the aid of a small telescope.

Websites like International Comet Quarterly and the British Astronomical Association’s Comet Section list currently active comets visible with an amateur telescope, and where they can be found.

Even if we know when a comet is likely to appear and the path it will take, no one can guess what it will behave like once it approaches the inner Solar System.

A comet could pass so close to the Sun that experts are sure it will be a spectacular view, only for it to break apart during perihelion, or give little more than a fizz of a tail.

However, once in a decade or so there is a comet that passes close enough to Earth and is bright enough to be seen with the naked eye.

When one of these is truly exceptional it may be bestowed the moniker of ‘Great Comet’; an apparition so magnificent it is remembered for centuries (or even millennia) to come.

Though in the past comets used to hold a bad name, as the portents of death and war, now these capricious visitors are a highlight for anyone lucky enough to see one as it passes by.

Where do comets come from?

After the planets formed, the material left over in the outer Solar System coalesced into a great many icy bodies.

These organised themselves into two regions. The inner of these is a ring between 4.5 and 7.4 billion km, known as the Kuiper Belt.

It’s thought that short-period comets come from this region.

Far beyond this, surrounding the entire Solar System, is a much larger cloud that is thought to stretch out 3.2 lightyears called the Oort Cloud.

Why comets have tails

The most alluring part of a comet is surely its huge tail, but what is not always obvious is that there are two.

The most apparent is the dust tail, which the solar wind sweeps out in an arc.

However, the magnetic field captures the gas, pulling it away to form a much fainter second tail.

Regardless of where the comet is in its orbit, the tails will point away from the Sun, rather than streaming behind as is often believed.

Astronomers have begun finding objects known as dark comets that look like asteroids but behave like comets.

Five famous comets

What are some of the most famous comets in history? These 5 comets will live long in the memory of comet chasers.

Comet Hale-Bopp

- Closest approach: 136 million km.

- Period: 2,520 to 2,533 years.

- Fact: Naked eye visible for a record 18 months in 1996 and 1997, Hale Bopp captured the public interest the world over.

Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko

- Closest approach: 186 million km.

- Period: 6.4 years.

- Fact: The target of the Rosetta mission, which studied the comet from orbit and sent the Philae lander to its surface.

Great Daylight Comet

- Closest approach: 19 million km.

- Period: 57,300 years.

- Fact: Spotted in January 1910, this comet quickly grew in brightness until it outshone even Venus.

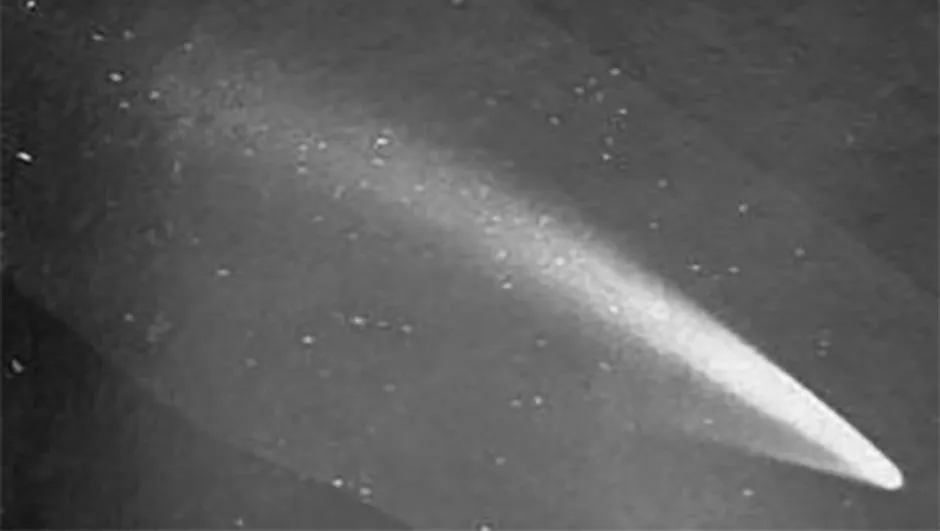

Halley’s Comet

Credit: NASA/W. Liller - NSSDC's Photo Gallery (NASA)

- Closest approach: 88 million km.

- Period: 75.3 years.

- Fact: This regular visitor was observed as early as 240 BC. It is often visible to the naked eye.

Comet Ikeya-Seki

- Closest approach: 450,000km.

- Period: 876.7 years.

- Fact: In 1965, Ikeya-Seki’s close pass of the Sun caused it to become one of brightest comets of the past millennia.

Photos of comets

Are you a comet-chaser or photographer? Keep us up to date with your observations and images by emailing contactus@skyatnightmagazine.com