In about 4.5 billion years the Milky Way will smash into the Andromeda Galaxy in an event already dubbed the Andromeda-Milky Way collision.

Astronomers are still attempting to predict what it will be like when the Andromeda Galaxy and the Milky Way eventually collide.

It's be known for a while that an Andromeda-Milky Way collision is inevitable.

Measurements of the Doppler shift of the Andromeda Galaxy's spectral lines indicate the galaxy is getting closer to our ow.

But such measurements can only tell you about the motion directly towards or away from the observer.

Working out if we were in for a direct hit or a near miss required careful study of the motion of Andromeda’s satellite galaxies.

They reveal Andromeda’s trajectory makes the Andromeda-Milky Way collision inevitable.

Plugging this information on the relative velocities, estimates of the masses of the galaxies and details of their structure into their model, the authors of an interesting paper on this galactic collision have watched the event unfold.

Though the details depend to some extent on galactic structure and in particular on assumptions we make about the haloes of dark matter that contain the visible discs of the Milky Way and Andromeda, the general picture is clear.

After a spectacular series of close passes lasting billions of years – and which will distort the structure of both galaxies – a final merger of the Andromeda Galaxy and the Milky Way galaxy will occur about 10 billion years from now.

What will happen during the Andromeda-Milky Way collision?

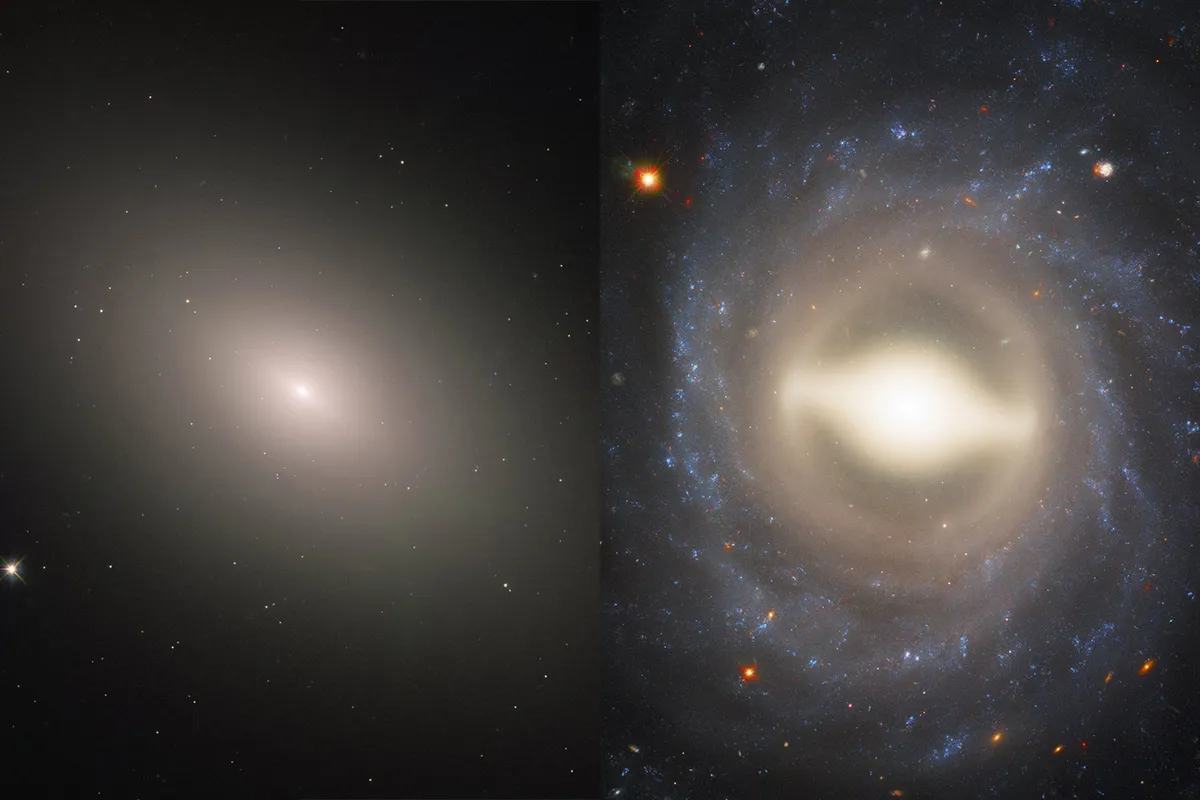

The result of the collision between Andromeda and the Milky Way will be a new, larger galaxy, but rather than being a spiral galaxy like its forebears, it ends up as a giant elliptical.

The authors of a paper have named this new galaxy ‘Milkdromeda’.

There’s something about this name that really bugs me. Surely we need something grander sounding?

If you can think of a better name for the Andromeda-Milky Way collision, let us know by emailing contactus@skyatnightmagazine.com.

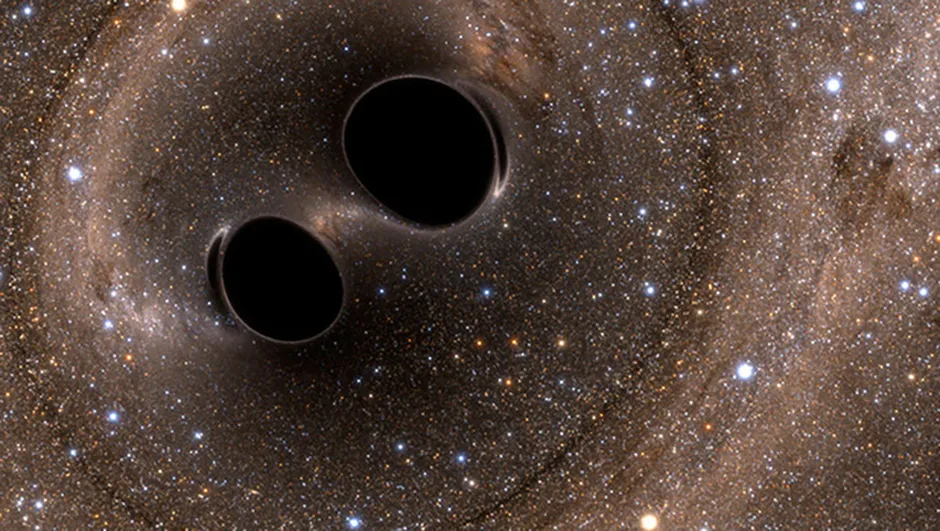

The simulation includes details of what happens to the supermassive black holes that lurk at both galaxy centres.

The black hole pair will end up forming a binary at the heart of the new, larger galaxy.

This binary isn’t stable, though. Interaction with their surroundings means that the pair will spiral inwards, emitting gravitational waves as they do so.

In only about 17 million years, the two will be close enough that the loss of energy through these gravitational waves drives a final inward spiral and merger.

The gravitational wave signal of an event like this can’t be detected by LIGO (the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory), which is sensitive only to the merging of lower mass black holes and neutron stars.

In the future, the simulations indicate that ESA’s LISA (Laser Interferometer Space Antenna) mission should observe such mergers out to an approximate redshift of two.

So we may be able to see how predictions of the fate of the Milky Way’s black hole match up to similar events elsewhere.

The authors’ estimate of 10 billion years for the Andromeda-Milky Way collision to reach its end is longer than in previous studies

But means the Sun will not live long enough to find a home in the new galaxy. We’ll have to enjoy the results of simulations instead.

Chris Lintott was reading Future merger of the Milky Way with Andromeda galaxy and the fate of their supermassive black holes by Riccardo Schiavi et al. Read it online at arxiv.org.

This article appeared in the April 2021 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.