Have you ever heard of an annular solar eclipse? They're also known as a 'ring of fire' eclipse, and are spectacular to behold.

Observers in North America most recently were able to enjoy one in 2023, during the October 14 annular solar eclipse.

And observers will be able to see the next annular eclipse on October 2, 2024 over Easter Island, Chile and Argentina.

In this guide we'll reveal what an annular solar eclipse is, why they happen and how they differ from a total solar eclipse.

Read our guide to find out when the next eclipse is occurring.

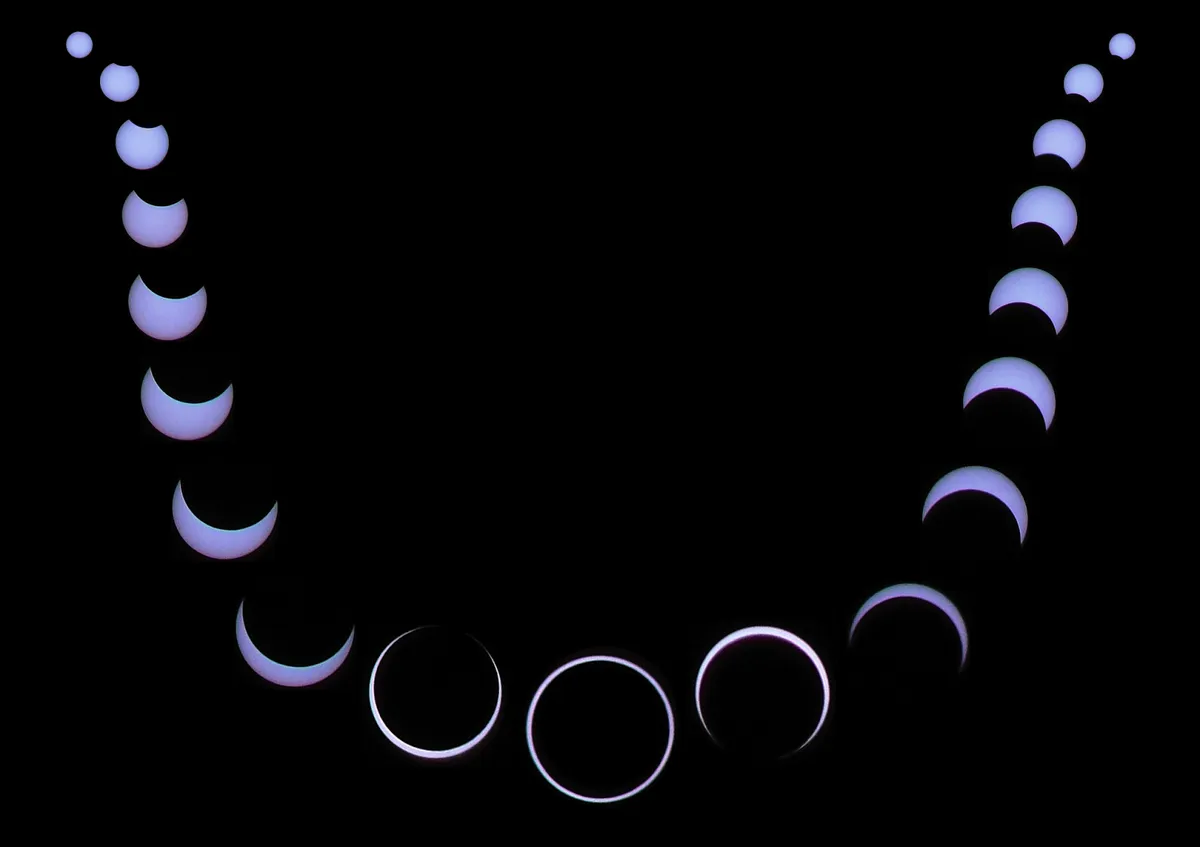

What annular solar eclipses look like

The mention of a solar eclipse conjures thoughts of totality and a glimpse of the Sun’s ghostly corona, the outermost part of its atmosphere, as day turns to night.

These are two effects of a total solar eclipse, but an annular solar eclipse is quite different.

Although the corona remains out of sight and daylight persists during an annular eclipse, they have other spectacular features, notably the ‘ring of fire’.

Observers see a thin, burning ‘ring’ around the Moon as 90% of the Sun is blocked.

The remaining 10% of the Sun’s face that remains visible around its perimeter is enough for daylight to persist

And to mean that an annular solar eclipse can only be safely viewed through eclipse glasses or solar filters.

So what exactly is going on when annular eclipses occur, and why do they differ from total solar eclipses?

Annular solar eclipse vs total solar eclipse

An annular solar eclipse happens when the Moon appears smaller than the Sun as it crosses its disc, and so doesn’t block out all of its light.

This happens because the Moon’s orbit around Earth is not a perfect circle but a slight ellipse shape.

There’s a point in the Moon’s orbit when it’s nearest Earth, perigee, and appears big enough to block the Sun’s disc

And a point when it’s farthest away, apogee, and doesn’t appear to cover the Sun.

The distance from the Moon to the centre of Earth changes from a maximum of around 406,000km at apogee to around 357,000km at perigee.

Whether there will actually be an eclipse in any given orbit of the Moon around Earth depends on whether the new Moon crosses the ecliptic – the apparent path of the Sun across the sky.

When an eclipse does occur during a perigee new Moon, it creates a cone-shaped umbral shadow in space.

And where the tip of this shadow touches Earth’s surface we see a total solar eclipse.

The 'ring of fire' explained

During the maximum phase of a total eclipse, along a narrow path of totality it’s possible to experience darkness in the day, as all of the Sun is obscured.

But when an eclipse happens at an apogee new Moon it’s not possible to witness totality anywhere.

During an annular solar eclipse the dark ‘umbral’ shadow cast by the Moon isn’t long enough to reach Earth.

This means observers along the path of annularity see a ‘ring of fire’.

Phases of an annular solar eclipse

What happens before and after maximum eclipse is very similar for both an annular and a total eclipse.

For around 80 minutes or more either side of totality or annularity, there’s a partial solar eclipse.

The new Moon approaches to take an increasingly larger bite out of the Sun, before moving away.

The difference is the few minutes in the middle.

Just as with a total eclipse, during an annular solar eclipse it makes a difference where you stand within the central path of annularity.

Along the centre line, the ‘ring of fire’ lasts the longest – up to 12 minutes.

But this decreases to just a second on the northern or southern edges of the path.

Those at the edge of the path may seem disadvantaged, but there’s a reason why some eclipse-chasers gather there.

Although a perfect ‘ring of fire’ is only momentarily visible, from these positions it’s possible to see Baily’s beads – spots of sunlight pouring through lunar mountains and valleys.

They flare for a few seconds and cause a ‘broken ring’.

Observing upcoming annular solar eclipses

The next annular solar eclipse will occur on October 2 2024 in the Pacific Ocean.

Perhaps the best place to witness annularity will be amid the carved human moai figures on Rapa Nui (Easter Island).

It will also be visible shortly before sunset from Patagonia in southern Chile and Argentina.

Eclipses are spectacular sights, yet we exist at a time when the Moon and Sun can be exactly the same apparent size in the sky to make total solar eclipses possible.

However, the Moon is slowly drifting away from Earth at a rate of 4cm per year.

There will come a time when it will no longer appear big enough to cover the whole Sun.

In about 563 million years, every solar eclipse will be annular.

How to safely observe a solar eclipse

Whether a total or an annular eclipse, when observing the Sun, caution must always be exercised.

Never look directly at the Sun with the naked eye, as doing so could seriously damage your eyesight.

For more info, read our guide on how to safely view an eclipse, or watch our video below:

This guide originally appeared in the October 2023 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.