Saying this will probably get me in trouble with my art-loving colleagues, but… I don’t think there’s a painting in the world that can compare to the beauty of the Universe.

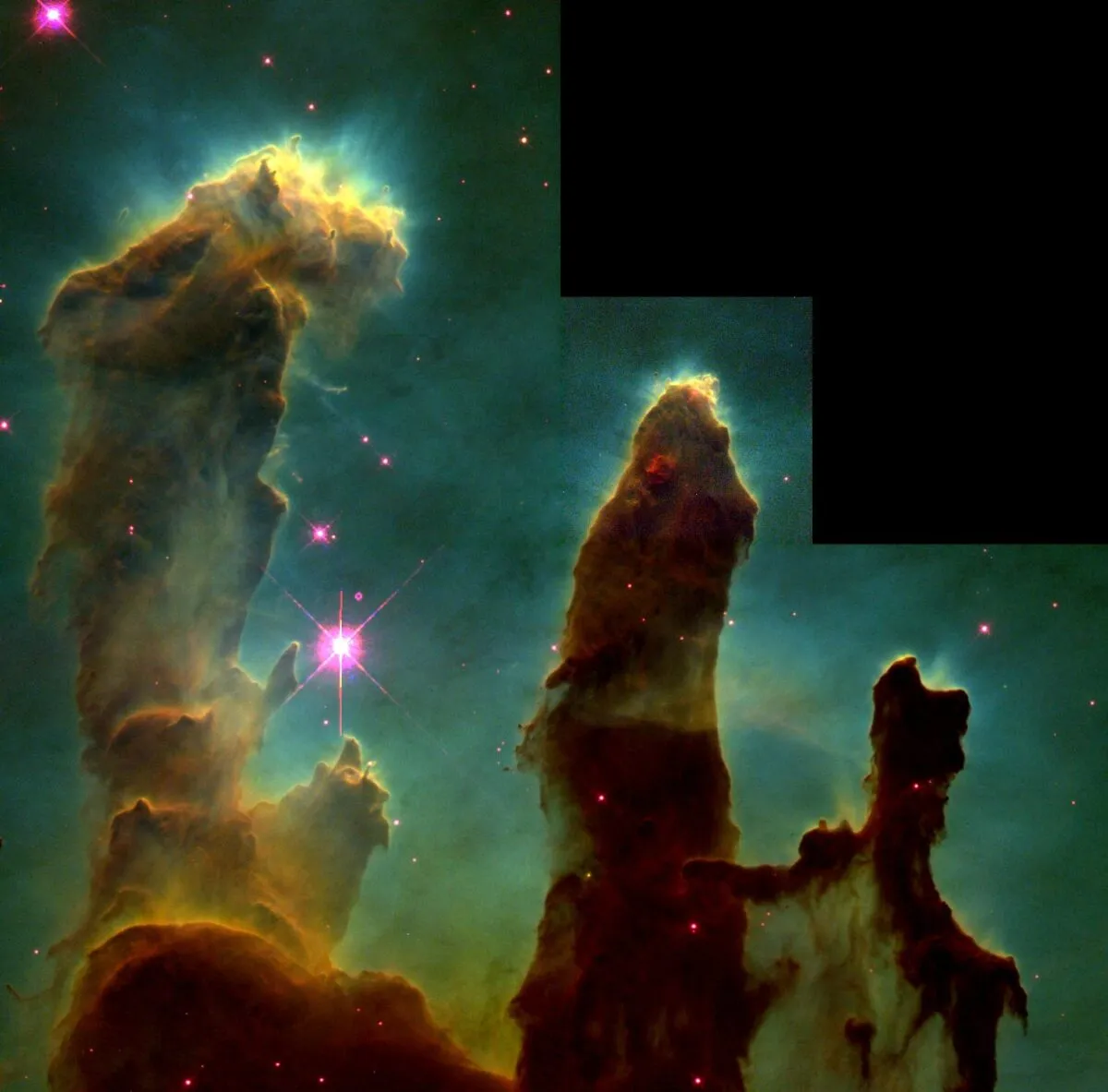

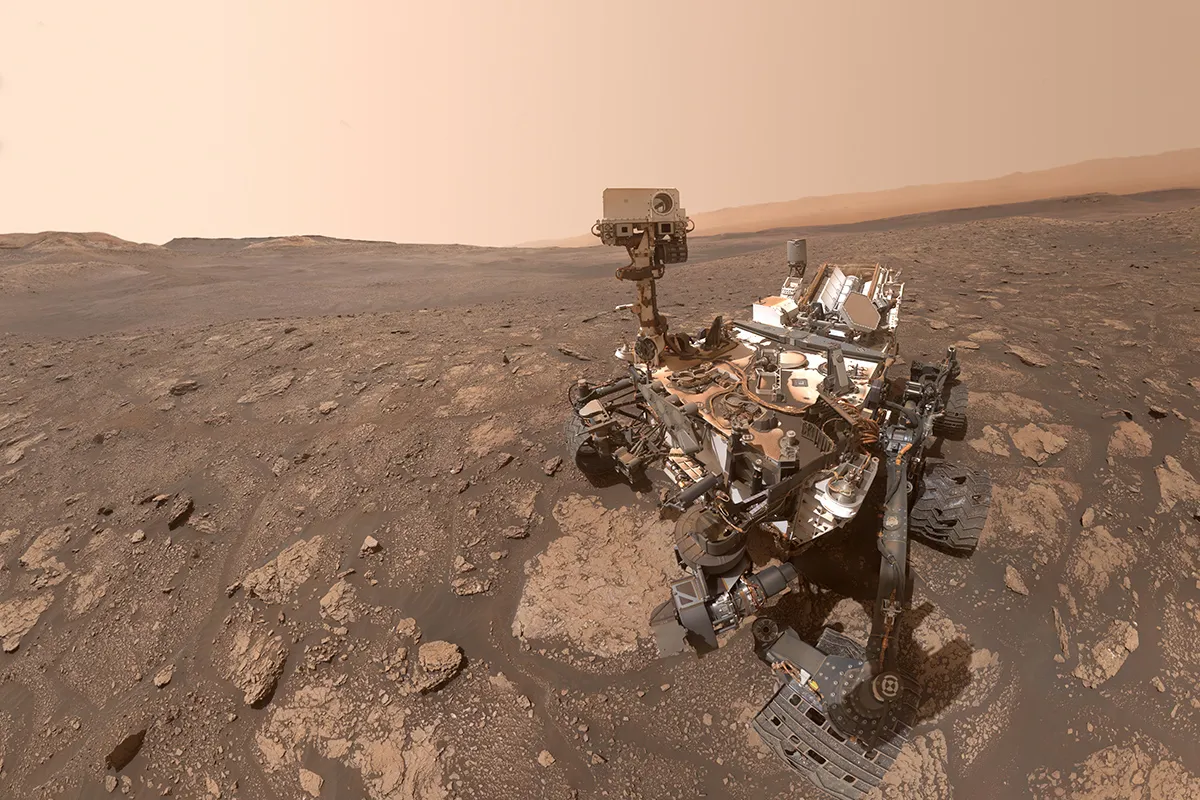

From the classic ‘Pillars of Creation’ photo taken by the Hubble Space Telescope, to Curiosity Rover’s selfies on Mars, and now the stunning first images coming from the James Webb Space Telescope, photographs of (and from) space are a source of inspiration to countless people around the world.

But these images aren’t just taken so that space nerds like me have pretty pictures to use as our computer backgrounds.

Astrophotography has fundamentally changed our understanding of the Universe.

Back in 1883, an amateur astronomer called Andrew Ainslie Common took a long-exposure photograph through his telescope of the Orion Nebula, revealing details in his astrophoto that were normally invisible to the eye.

By the early 20th century, astrophotography was commonplace in professional observatories like the Harvard Observatory, where women including Williamina Fleming and Henrietta Swan Leavitt worked as human ‘computers’, cataloguing and classifying stars in photographic plates.

Later, in 1925, Edwin Hubble was examining photographs of the Andromeda Galaxy and spotted Cepheid variable stars, which he then used to calculate the galaxy’s distance.

His measurements placed the Andromeda Galaxy firmly outside our Milky Way Galaxy, finally resolving astronomy's great debate about the nature of ‘spiral nebulae’ (as galaxies were referred to then) and the size of our Universe.

Into the modern era...

Modern telescopes have moved beyond photographic plates, but the principles remain the same.

Point a telescope at something, gather as much light as possible during a long exposure to bring out the details, and perhaps see something unexpected.

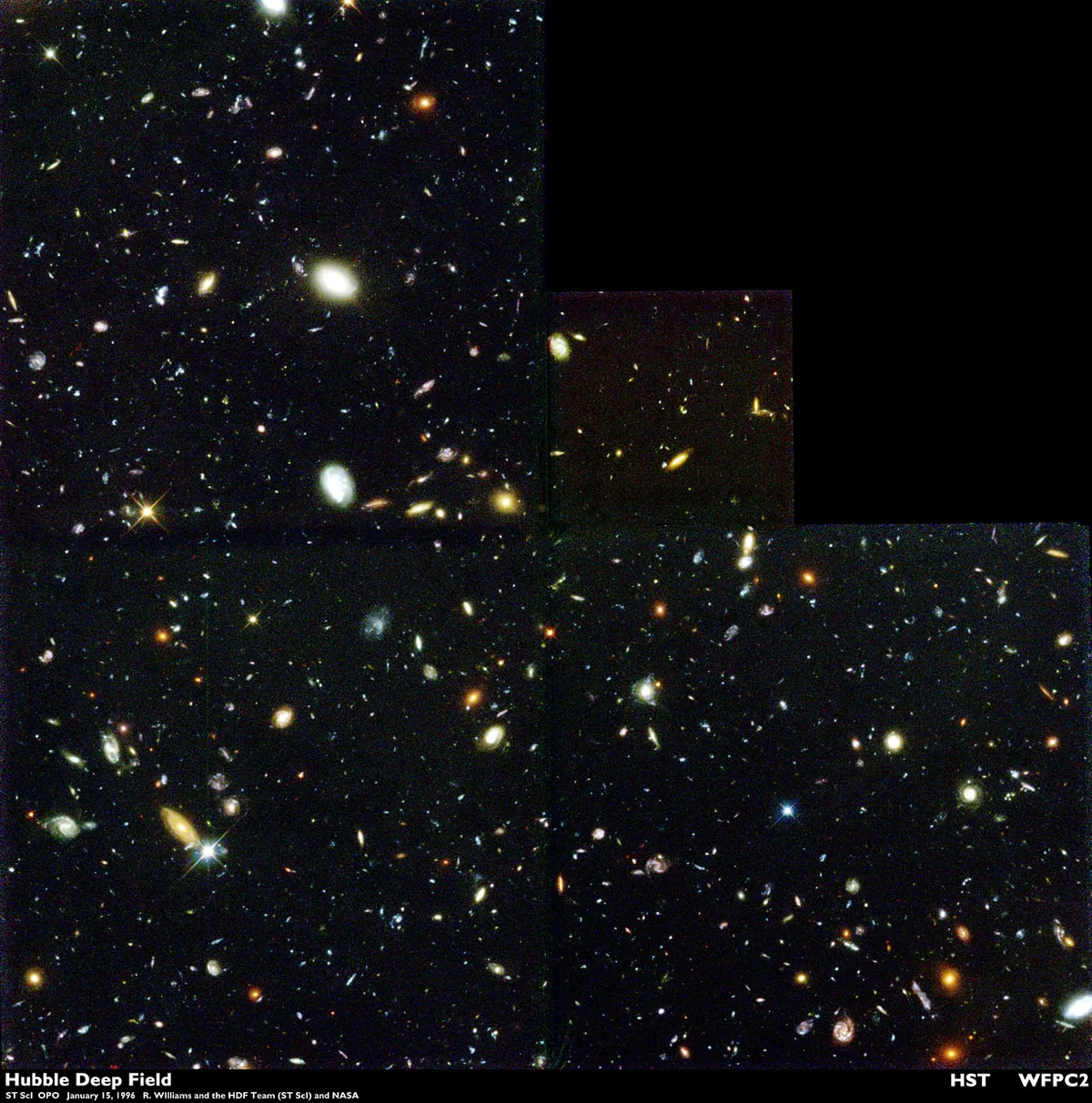

The Hubble Deep Field image is probably my favourite example of this.

In 1995, Robert Williams, director of the Space Telescope Science Institute, pointed Hubble at a tiny, seemingly empty, part of the sky for over 100 hours.

The resulting image revealed around 3,000 distant galaxies crammed into a patch of sky the size of a pinhead held at arm’s length.

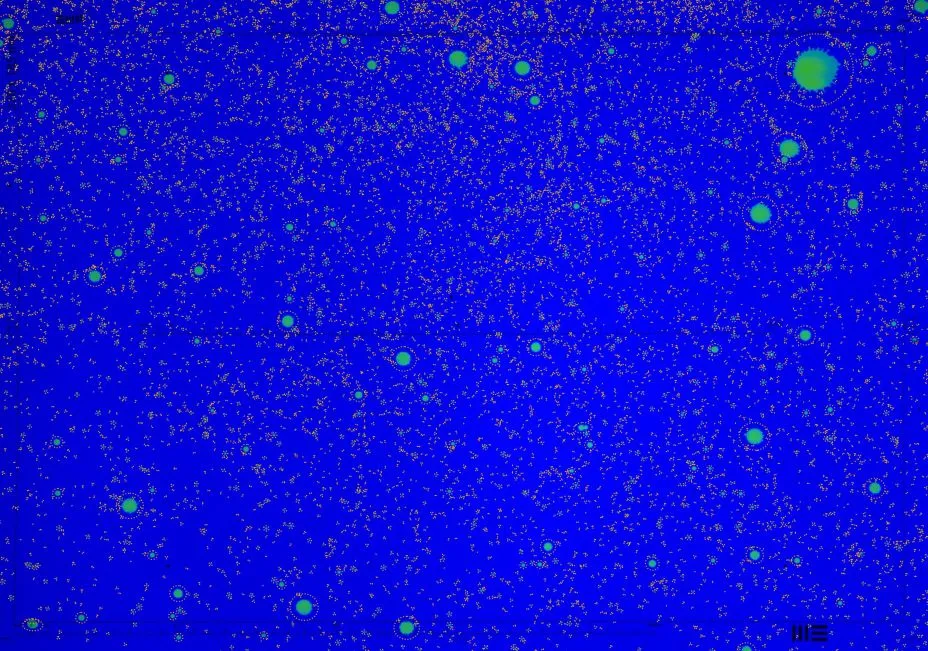

The analysis of astronomical images can also lead us down unexpected paths, as my colleagues at the University of Portsmouth recently found out during the Covid pandemic.

It turns out that computer codes used to automatically find galaxies in astronomical images can also be used to identify cough droplets!

The team used fluorescent dye in a ‘cough machine’ to simulate a person coughing.

They then took photos of the resulting cough spray and applied the same computer code to these photographs to pick out where the cough droplets landed.

This unusual application of an astronomical tool allowed the team to study how droplets spread from a cough, something that’s obviously important in fighting the spread of COVID-19.

Of course, we need to remember that these beautiful images are not accessible for everyone.

A reliance on using imagery to convey how awe-inspiring the cosmos is has the potential to exclude people who are blind and vision-impaired.

This is why there’s a growing number of projects around the world that are working on ways for people to interact with astronomical observations through the other senses.

At the University of Portsmouth we run the Tactile Universe project where we make 3D printed versions of astronomical images so that they can be felt instead of seen, allowing everyone to experience the wonder of the Universe that surrounds us.

This article originally appeared in the October 2022 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.