Remember in Star Wars: A New Hope when Luke Skywalker looks out across the Tatooine landscape to see the planet's two suns setting on the horizon?

Most of us will remember seeing that image for the first time and thinking how cool it was: how sci-fi.

This, of course, was 20 years before the first ever confirmed detection of a planet orbiting a star beyond our Solar System - an exoplanet - and since that scene first graced cinemas, astronomers have been able to confirm that such 'Tatooine' planets do indeed exist.

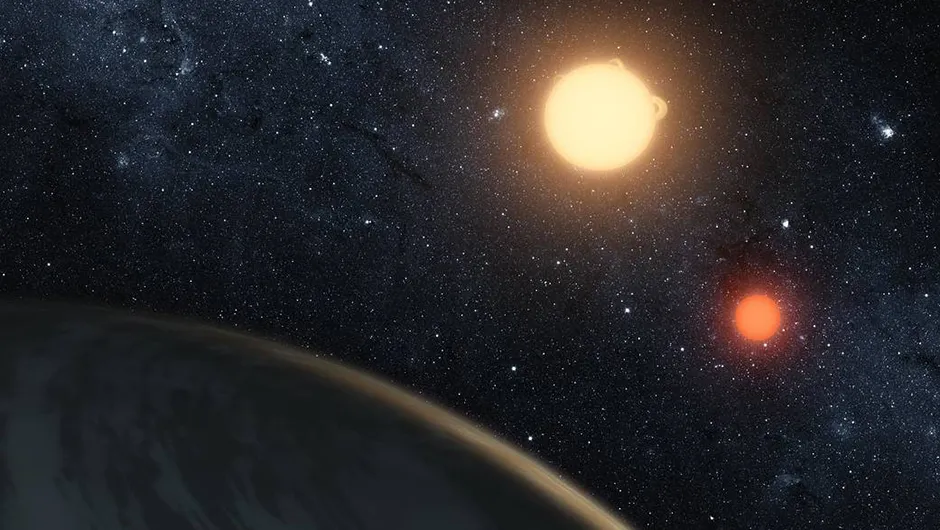

There are planets in our galaxy that orbit a pair of stars at once: these systems are known as circumbinary systems.

Binary systems refer to two stars orbiting around a common centre of mass.

In general, circumbinary systems are ones where a planet orbits around a pair of stars, rather than orbiting around a single star.

And there is even another type of binary planet system where a planet orbits around just one star in a binary pair.

To find out more about these circumbinary Tatooine worlds, we spoke to Lalitha Sairam, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Birmingham working on the discovery and characterisation of exoplanets.

She and her colleagues found exoplanet BEBOP-1c, the second ‘Tatooine’ world found orbiting its twin stars, making it the second such world found in that binary system.

How many circumbinary 'Tatooine' worlds have been discovered?

There have been about 14 transiting planets discovered orbiting around 12 binary stars.

They are quite rare primarily because of our limitations in observing them and validating them, all of which require tremendous amounts of time.

As you go out and look at the night sky, nearly 75% of the stars you see are in multiple systems, so binary stars are quite common.

If we extrapolate from what we know about single stars, we should be able to discover many more planets in circumbinary systems using improved techniques and improved telescopes.

How did you find one?

Our idea was to carry out something known as ‘radial velocity measurements’ of binary stars, as part of a survey called Binaries Escorted By Orbiting Planets (BEBOP), observing in both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres.

In 2020, there was an announcement that the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) had observed a circumbinary planet in a system called TOI-1338 b.

We immediately began to look for this planet, but we didn’t have enough observing time to be able to see it, so we made further observations of the system with the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (VLT).

When we started analysing the data, what we saw wasn’t the planet that was announced initially, which had around a 95-day orbital period; instead we started seeing a signal around 220 days.

Through further analysis, the signal started to become more prominent and this 220-day orbital period planet is now called BEBOP-1c

This made it the second-ever discovery of a multiplanetary circumbinary system.

What is the ‘radial velocity method’?

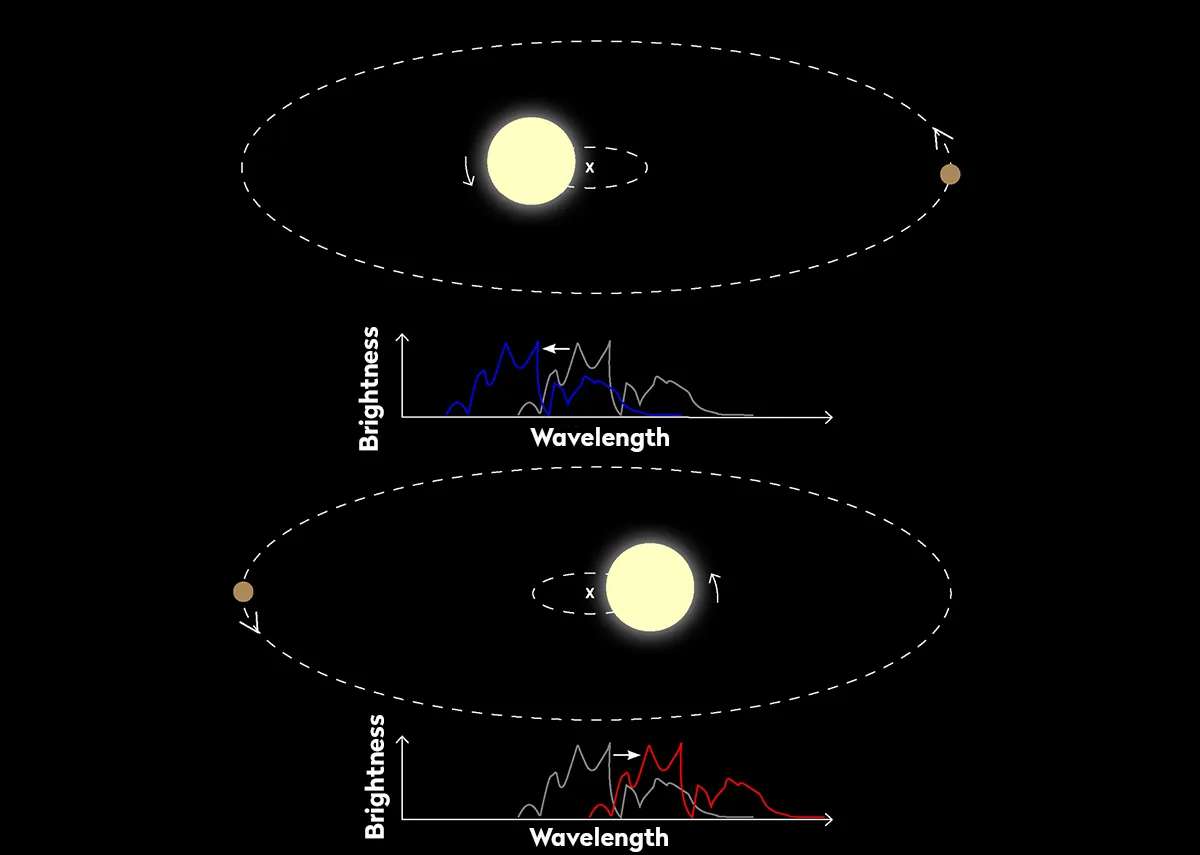

We know that two bodies in orbit exert a gravitational pull on one another.

When you sit here on Earth and observe a star–planet system, the gravitational tug-of-war happening causes the star to wobble, shifting the light from the star towards and away from you.

This is called redshift and blueshift.

By measuring the size of the shift, you can measure how massive the body is that is exerting the gravitational pull.

This is how the first-ever exoplanet, 51 Pegasi b, was discovered.

What can we learn from studying circumbinary planets?

They challenge our ideas of how planets are formed.

We see these planets are formed in more complex environments, so their formation process may be quite different compared to what we have known.

But generally, what’s interesting for people that have watched Star Wars, is that BEBOP-1c is a ‘Tatooine-like’ planet.

Tatooine is the fictional home of Star Wars’s Luke Skywalker and it has two suns and two sunrises.

On BEBOP-1c – if the planet had a surface – then you would see two sunrises, just like on Tatooine.

Unfortunately, the parallels end there, but it’s a nice way for people to look at astronomy as a mix of fiction that they can relate to real life.

Could a planet ever have three stars?

There have been measurements suggesting there could be planets orbiting around three stars, but no conclusive evidence as of now.

It is the case that maybe these planets will be further away from the star itself for them to survive.

If they’re very close, the gravitational pull from three stars is going to be too unstable for the planet to survive.

And this means there would be long waiting times for us to be able to detect these planets.

This interview originally appeared in the September 2023 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.