Over the coming years, as astronomers use spectroscopy to read the atmospheres of Earth-sized, habitable exoplanets, detecting the presence of one gas will be an important discovery: oxygen.

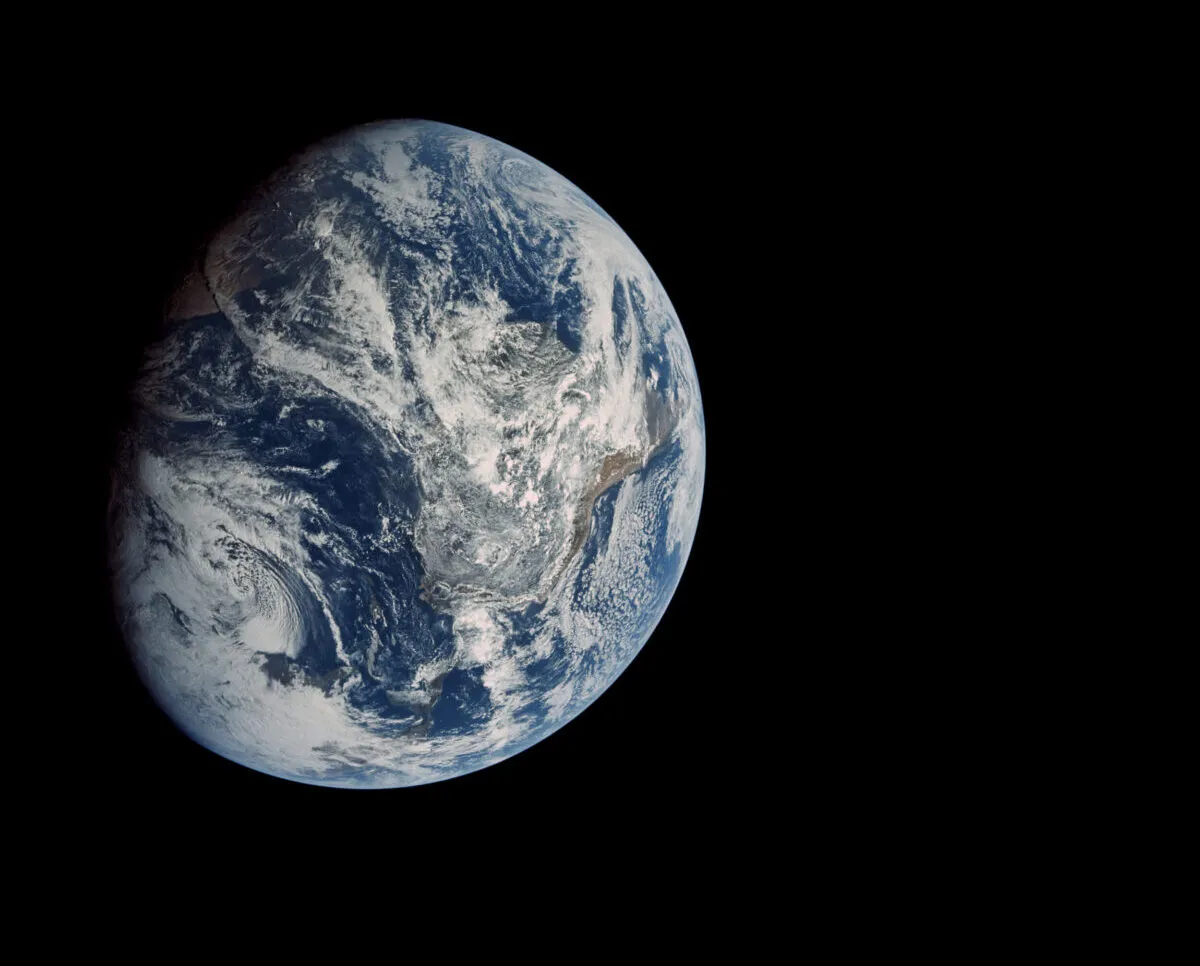

On Earth, oxygen is released by life – specifically, by organisms using sunlight for energy.

Oxygen is a very reactive gas. Early in Earth’s history any oxygen released into the atmosphere was rapidly removed.

It reacted with rocks, or was destroyed by photochemical reactions driven by ultraviolet rays in sunlight.

More from Lewis Dartnell:

- What if a hot Jupiter existed in our Solar System?

- How James Webb Space Telescope will study exoplanets

- Why are there so many different kinds of planet?

Such processes are known as ‘sinks’, and oxygen only started to accumulate in Earth’s atmosphere once its production had overwhelmed these sinks.

An oxygen-rich atmosphere is thought to be a sign of flourishing life on a world, which is why astronomers would be so excited about discovering one on an exoplanet.

But is oxygen the only ‘biosignature’ gas that would indicate the presence of life on an exoplanet?

Might other gases produced by biochemistry also be able to overwhelm the sinks on their exoplanets and accumulate to detectable levels?

Sukrit Ranjan, at Northwestern University, and his colleagues have been investigating this.

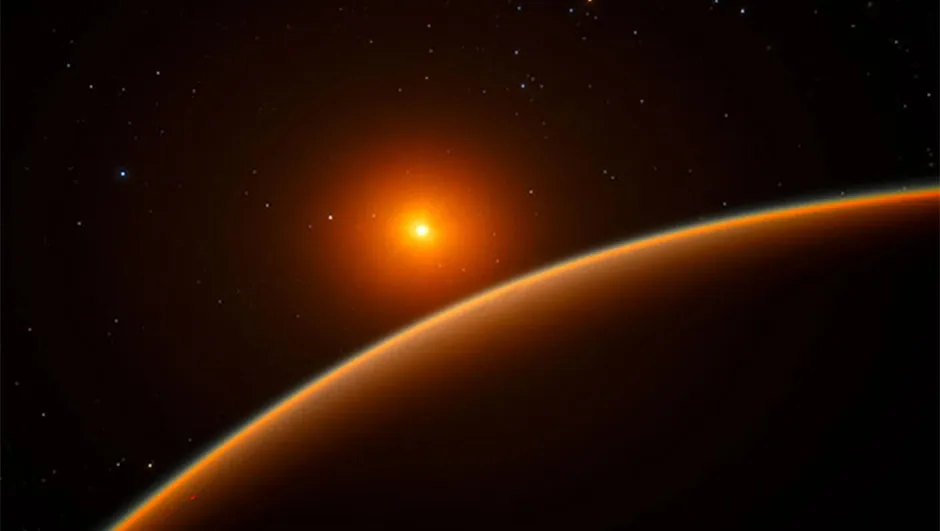

The best candidate worlds for detecting such biosignature gases, they argue, are exoplanets orbiting small, cool M-class red dwarf stars.

Such stars emit less ultraviolet radiation than larger, hotter stars like the Sun, and so the sinks on those planets are much weaker.

Exoplanets orbiting M-class red dwarfs offer favourable conditions for the accumulation of reactive gases to levels that we could hopefully detect with space telescopes.

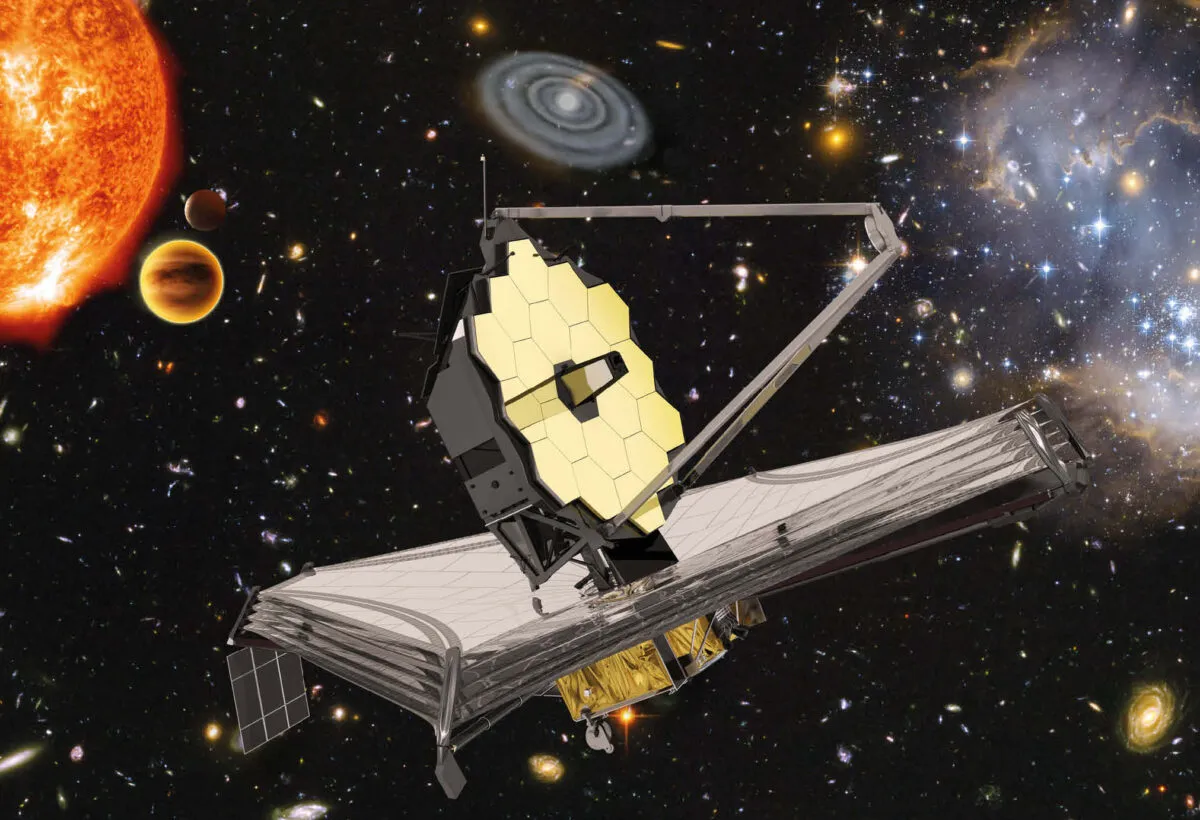

This is one of the reasons why the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is targeting these stars.

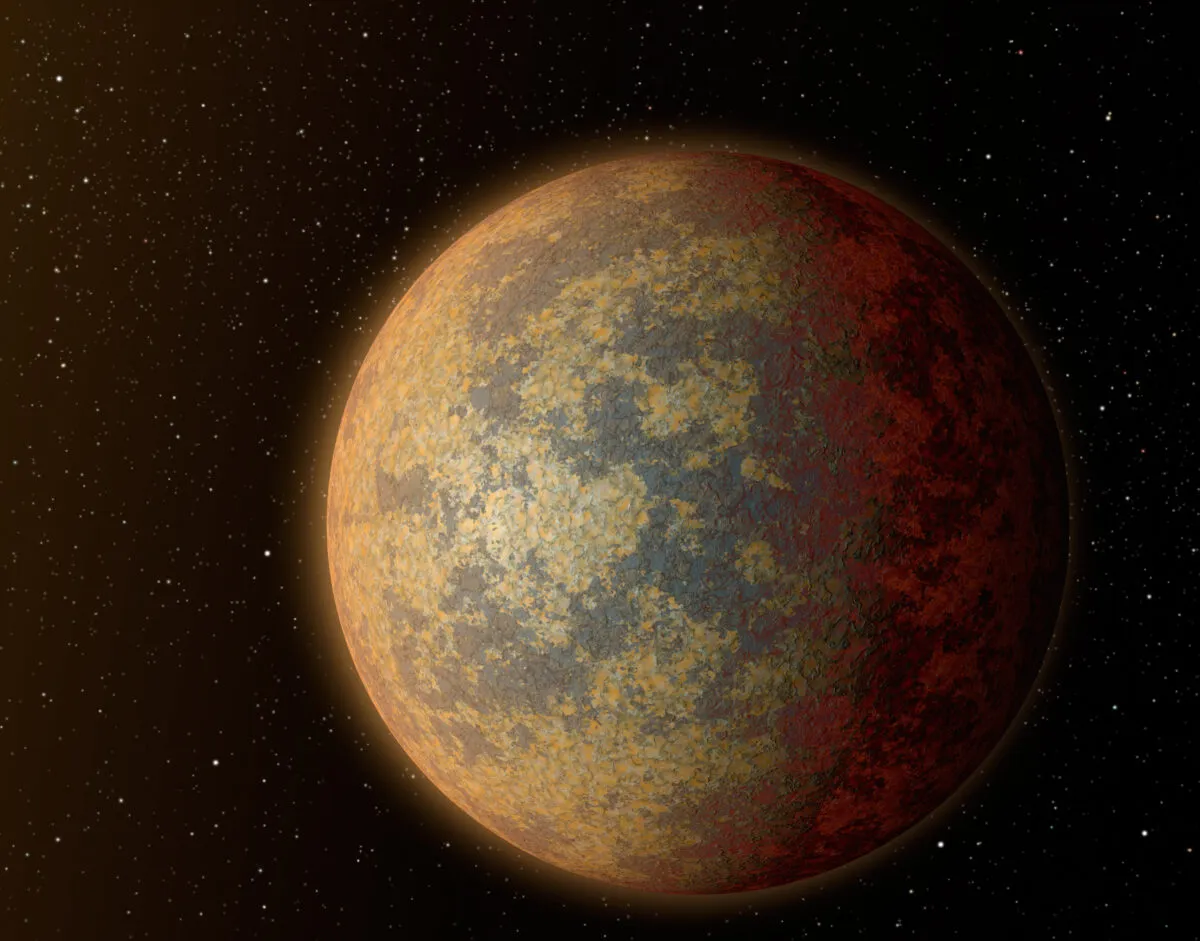

Ranjan’s team considered an exoplanet with a hydrogen/nitrogen atmosphere in orbit around a M-class red dwarf.

The biochemistry of life on such a world might produce ammonia (like on Earth, where Rhizobacteria help nitrogen-fixing plants to draw nitrogen gas from the air).

This scenario has been nicknamed a ‘Cold Haber World’, after the process that uses heat, pressure and a catalyst to convert atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia for fertilisers.

The research team simulated a Cold Haber World with a climate suitable for oceans of liquid water, Earth-like volcanism and an atmosphere with the same surface pressure as Earth, but made up of 90% hydrogen and 10% nitrogen.

They simulated how quickly life on such a planet would release ammonia and the rate at which atmospheric ammonia would be destroyed by the dwarf star’s sunlight.

They found that for realistic biological ammonia production rates, the gas can overwhelm the sinks on the planet and accumulate to notable levels in the atmosphere.

They claim the JWST could detect such an atmospheric biosignature with two transits over two months.

Such a world would be different to Earth, but this result gives astronomers hope that we’ll be able to remotely detect atmospheric biosignatures on more diverse exoplanets.

Lewis Dartnell was reading Photochemical Runaway in Exoplanet Atmospheres: Implications for Biosignatures by Sukrit Ranjan et al. Read it online at: arxiv.org/abs/2201.08359.

This article originally appeared in the April 2022 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.