You might assume it would be difficult to confuse a galaxy and a star, and yet that’s the story of ‘BL Lac’ objects. Named after the first example that was found in the otherwise obscure constellation of Lacerta, BL Lacertae objects show rapid and significant changes in brightness, and were originally thought to be a rare form of variable star.

We now know that their light comes not from a star at all, but from the centres of active galaxies, as material falls onto the supermassive black holes that lurk there.

Read more from Chris Lintott:

- How do black holes form?

- Why do some galaxies have more supernovae than others?

- Black hole jets may be more unpredictable than thought

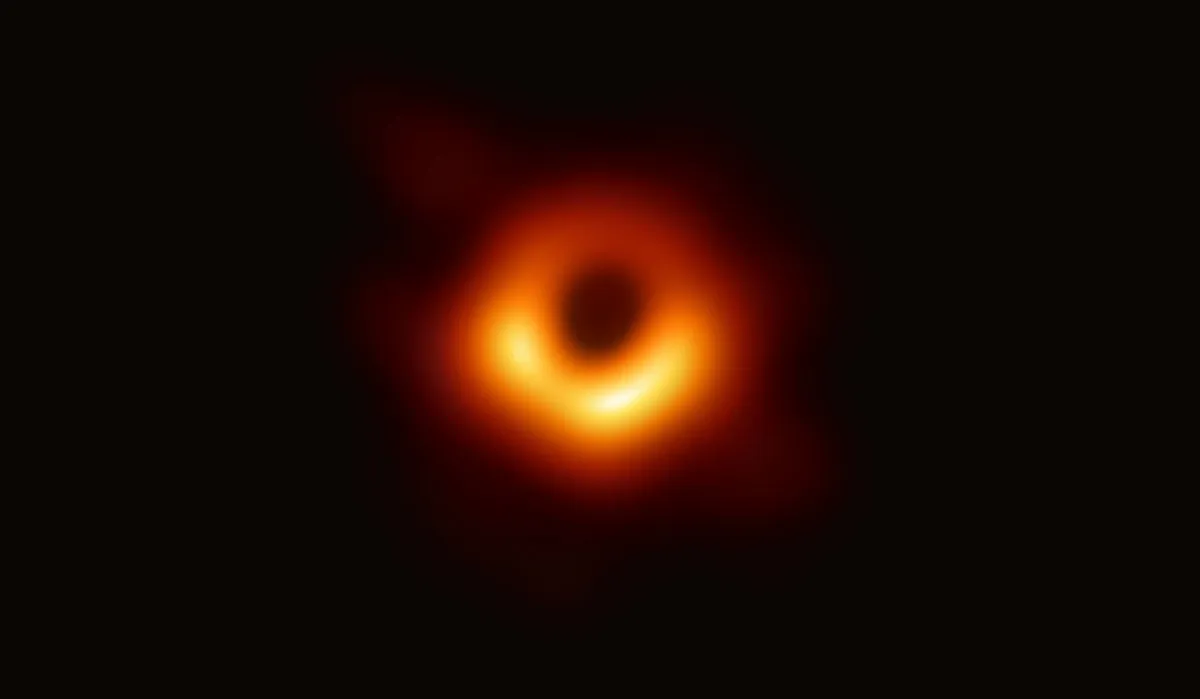

When enough material falls towards the centre of a galaxy, first an accretion disk forms – as seen in that wonderful first image of a supermassive black hole from the Event Horizon Telescope, released in 2019 (pictured below) – and then some can be expelled in a rapidly moving jet.

In the case of BL Lac objects, conditions are so extreme that the jets sometimes seem (thanks to a quirk of geometry) to be moving faster than the speed of light.

The strange behaviour of BL Lac might be explained if we’re staring down the barrel of the jet itself.

The rapid changes in brightness seen in both visible light and at radio wavelengths are then explained by the behaviour of material in the jet, rather than around the black hole itself.

Testing this idea is hard, though, and the authors of a paper led by Francesco Massaro of the University of Turin have had a good idea.

Assembling a collection of massive elliptical galaxies that host BL Lac objects, they looked at their environments and whether they’re found in dense clusters of galaxies, the middle of empty voids, or somewhere in between.

This is difficult to do precisely, but a good estimate can be made just by counting a system’s neighbours. After all, if you have more neighbours you live in a more crowded area!

Once the count is complete, comparisons can be made with other sorts of objects: in this case, with other types of active galaxies.

If we get a BL Lac when we stare down the jet, there should be a whole population of galaxies out there that are the same, except that the jet points in another direction. Those other systems should be found in the same kind of environment.

The prime candidate is a type of active galaxy called an FR I, but the authors show convincingly that these live in more crowded environments, and so they can’t be the ‘hidden’ BL Lacs.

However, the BL Lacs do match another population in environment: they live in the same places in the Universe as a type of galaxy called an FR 0.These are essentially bright points of radio emission.

This result is itself a mystery – why should the most spectacular examples of active galaxies share an environment with these relatively quiet systems?

One answer, proposed by the team, is that the high energy jets we see in the most active systems are actually a ubiquitous feature of galaxies with growing black holes.

If the jet points towards us, we get a BL Lac, and if it doesn’t we see a nice, quiet system.

If jets really are this common, we’ll need to explain how such jets form – and can expect a jet to have been a feature of our own Milky Way’s past.

Chris Lintott was reading Dragon’s Lair: on the large-scale environment of BL Lac objectsby F Massaro et al.Read it online at https://arxiv.org/abs/2009.03318.

This article originally appeared in the November 2020 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.