The Aurora Borealis – literally ‘northern dawn’ – was given its name by Galileo, who mistakenly thought it was caused by sunlight reflected from the atmosphere.

A similar light show in the southern hemisphere is now known as the Aurora Australis. But the phenomenon has been witnessed throughout history.

Stone Age cave paintings in Europe dating back 30,000 years are believed to depict early displays, while the Greek philosopher Aristotle compared it to fires on Earth in 344BC.

- A traveller's guide to aurora hunting

- How do you take photographs of the aurora?

- What do aurorae look like on other planets?

These atmospheric displays are usually seen in high regions of latitude, north and south, around the poles. But more powerful displays penetrate further and rare, major shows

can be seen from southern Europe or the USA. In 34AD, Roman troops marched on the city of Ostia in Italy because a bright aurora convinced Tiberius Caesar that the town was in flames.

In the 18th century, the leading American thinker Benjamin Franklin suggested that aurorae were created by electrical charges concentrated around the poles and intensified by snow and moisture.

Then, in September 1859, brilliant red, green and purple auroral displays encircled the Earth, visible even in the tropics.

It happened just a day after a British astronomer, Richard Carrington, had observed two blinding beads of white light appear briefly above a sunspot, an explosion that was the earliest recorded solar flare.

The two events set astronomers on track to link events on the Sun with the heavenly fireworks.

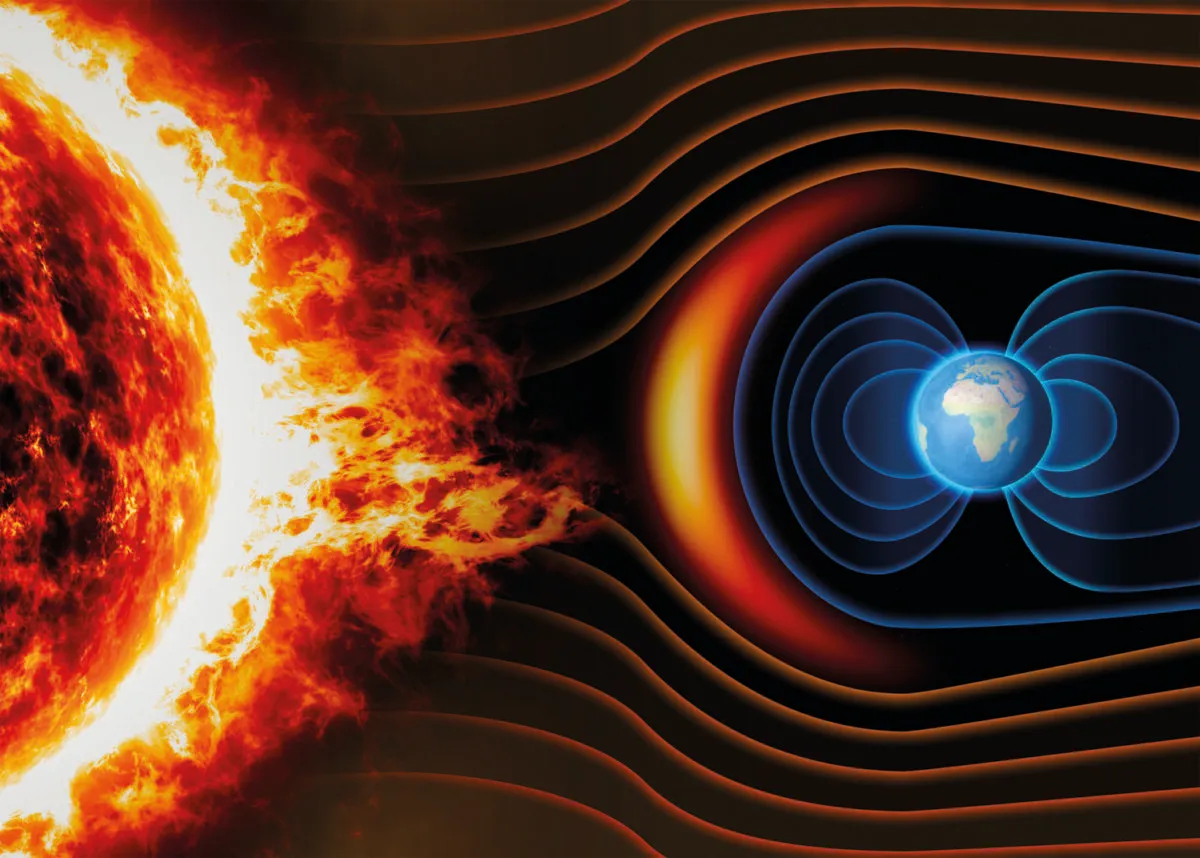

The aurora is now known to occur when the solar wind, a stream of charged particles – protons and electrons – flowing from the Sun, collides with the Earth’s upper atmosphere.

Our planet is surrounded by a vast magnetic bubble – a natural shield called the magnetosphere that protects us against deadly radiation from space and the solar wind.

This magnetic field is thought to be generated by a dynamo process in our planet’s liquid core.

Field lines in the magnetosphere channel some of this stream from the Sun towards the Earth’s magnetic poles.

The solar particles collide with atoms and molecules in the ionosphere, causing these molecules to release energy, which they do by glowing brightly.

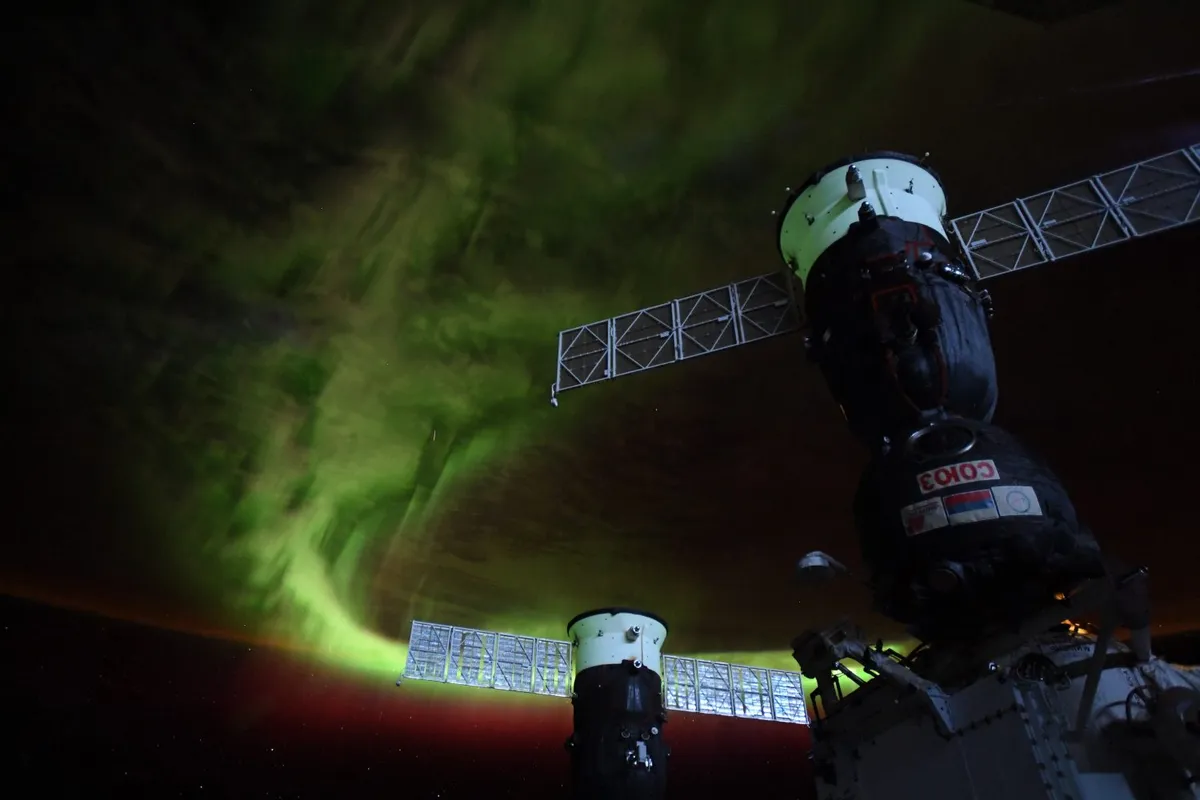

Aurorae can take various forms, from a gentle glow near the horizon to arcs, rippling bands and streaks of light.

Brighter and more dramatic shows can resemble constantly shifting curtains or even a corona, where rays radiating from overhead appear to fill the sky.

The most common colour for an aurora is green, but other displays can be red or purple, depending on which atoms of gas the charged solar particles have struck.

Though these colours appear striking in photographs, this is due to the time exposures used; the brightness and colour usually appears more subtle to the eye.