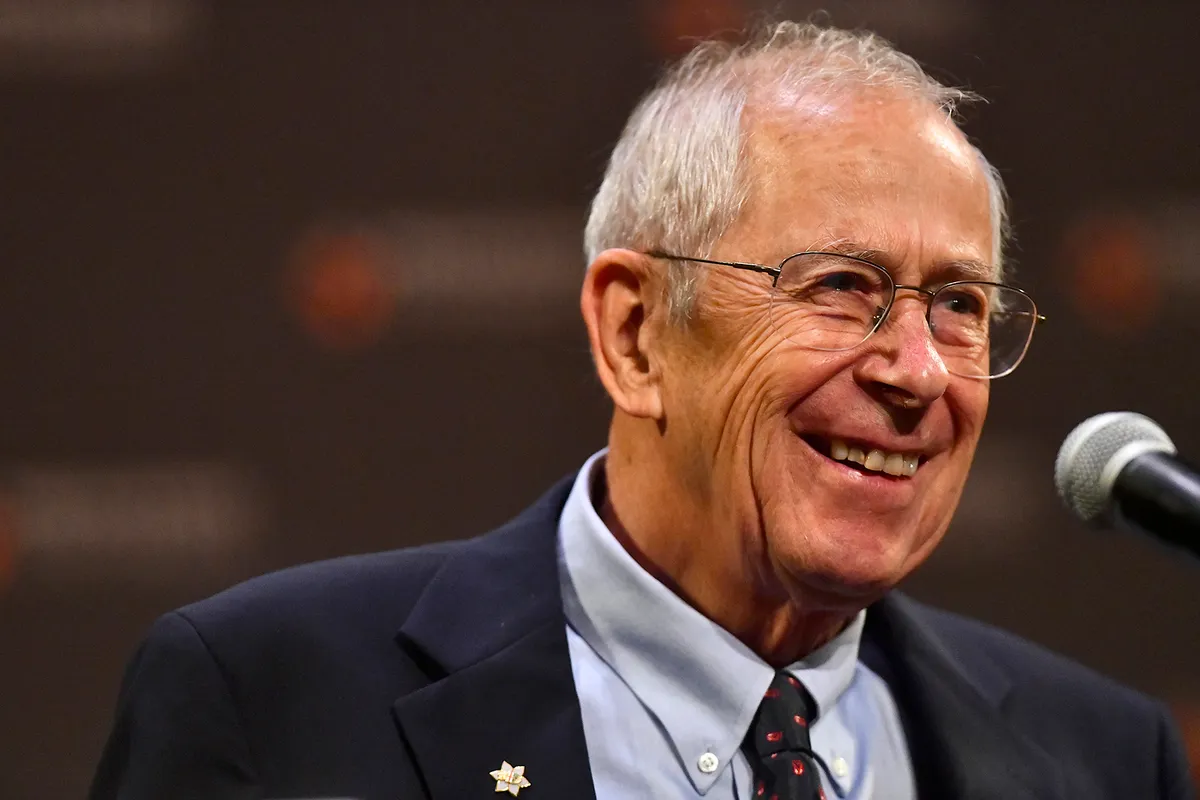

Nobel-prize winning physicist Phillip James Edwin Peebles is one of the most influential scientists alive. In 2019 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics for 'theoretical discoveries in physical cosmology', sharing the award with Michael Mayor and Didier Queloz for their first 'discovery of an exoplanet orbiting a solar-type star'.

Peebles' new book Cosmology's Century, published by Princeton University Press, is an account of the field of cosmology and how it has developed over time.

We got the chance to talk to Peebles and get his thoughts on the subject.

What is cosmology, and when did it begin?

Cosmology is an ancient art.

Physical cosmology is the theory and observation of the nature of the physical universe based on what we know about it on the largest scales we can observe.

This line of research traces back a century ago to Einstein's thought that a logically constructed universe is the same everywhere, no edges.

Others soon added the astronomical evidence that this near uniform universe is uniformly expanding.

We now have a theory that passes many tight and demanding tests, which makes a persuasive case that our theory is a useful approximation.

The theory certainly is not complete, but then all of physical science is incomplete. That's why we're still employed.

Do cosmologists observe the Universe like astronomers?

Cosmology used to be uncomfortably short of observational evidence, but advances in the last quarter century changed that.

We still rely on theory, but now the theory passes a serious network of tests. I put cosmologists' present use of data in the same class as astronomers looking at the sky and physicists working in the laboratory.

Do many of early cosmology's findings still hold up today?

A half century ago there were serious advocates of the steady-state idea, and others were arguing that the Universe of matter seems to have edges.

Both are clearly ruled out. Other old ideas stand.

The argument that the Universe is expanding traces back to the 1920s. The idea that the early Universe was hot originated in the late 1940s. Both pass many tests now.

Does it frustrate you that we don't know what the majority of the Universe is made of?

No. There are many things we can be very sure we never will know.

For example, what is happening on planets around stars in another galaxy? The human race will never know.

I am excited that experiments in progress may actually tell us something more definite about the nature of the dark matter.

No one promised we can discover that, or anything, but we still are learning many things.

Of all your achievements throughout your cosmological career, of which are you most proud?

Riding the wave of observational advances that prove to substantiate many of my ideas, sometimes even those I distrusted, particularly the notion ofdark matter.

If there was one question that you could instantly know the answer to, what would it be?

That would be no fun. But I must admit I would not complain if I were to be informed of the composition of the dark matter.

Cosmology's Century: a review

Words: Giles Sparrow

Among astronomy’s many achievements in the 20th century, the prediction and discovery of the cosmic microwave background radiation (CMBR) is surely one of the greatest. It not only clinched the case for the Universe’s origin in a ‘Big Bang’ 13.8 billion years ago, but also provided a new means of studying the early cosmos.

As a PhD researcher at Princeton in the early 1960s, Jim Peebles was among the team that predicted the CMBR’s existence, while his subsequent career focused on developing ideas about the evolution of cosmic structure and the role of mysterious dark matter, for all of which he was awarded the 2019 Nobel Prize in physics.

It’s hard then to imagine anyone better placed to recount the inside story of modern cosmology.

Unusually among his contemporaries, Peebles has always taken a keen interest in the origins of the ideas with which he wrestles each day, and his latest book is a magisterial summing up of a century of science, from Einstein’s 1915 general theory of relativity, to the turn of the millennium and beyond.

Rather than opt for a strictly chronological approach, he tackles his subject through the development of particular ideas and concepts, such as Einstein’s principle that the Universe must be homogeneous (uniform) on the largest scale, the various ‘fossils’ (including the CMBR) that can tell us about the early Universe, and the rival and sometimes complementary models used in modern cosmology.

Delving into archives and recalling a lifetime of contacts with other key players, he offers a unique perspective on how some of the mind-bending ideas we now take for granted came about.

The academic structure of numbered sections and subsections, and exhaustive references may be off-putting to some, and of course the use of equations is sometimes unavoidable when discussing the scientific minutiae, but Peebles’ text is a model of unshowy clarity throughout, and the gist of his arguments and stories remains easy to follow even if you want to ‘skip the math’.

For anyone seriously interested in the ways of science and how we came to understand our place in the Universe, this is essential reading.

Iain Todd is BBC Sky at Night Magazine's Staff Writer. Giles Sparrow is a science writer and a fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society

This review and interview originally appeared in the June 2020 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.