One of my great pleasures is huddling up safe inside, while an awesome lightning display tears the heavens apart with booms of thunder. Earth is not unique in generating such electrical storms in its atmosphere. Lightning has been observed in the cloud decks of both Jupiter and Saturn, inferred on Uranus and Neptune, and is also debated to be present on Venus.

Lightning occurs if collisions between cloud particles create enough of an electrical ‘potential difference’ that it overcomes the insulating properties of the air, allowing a discharge to spark.

On Earth it’s not only the turbulent convection within storm clouds that can generate the necessary potential differences, but also the rising ash plumes of volcanic eruptions.

Read more from Lewis Dartnell:

- Can an exomoon help planets grow?

- Does oxygen on an exoplanet indicate an Earth-like world?

- Is it possible to make a map of an exoplanet?

But the sparks of lightning are only one aspect of Earth’s dynamic atmosphere building up steep differences in electrical charge.

In fact, the entire planet Earth behaves like a giant electric circuit, known as the global atmospheric electrical circuit (GEC).

Lightning shoots electrons towards the ground, and so thunderstorms generate an electric potential difference – the planet surface becomes negative and the ionosphere (the high upper atmosphere) becomes positive.

Just like across the two terminals of a battery, this voltage drives an electrical current of charged particles between the ionosphere and the surface.

Crucially, a ‘fair weather current’ is needed to complete this circuit between the Earth’s negatively-charged surface and positive ionosphere.The GEC needs lighting storms and regions of clear skies.

This GEC has an effect on weather patterns and atmospheric physics. Lightning can drive a lot of key gas chemistry – on Earth, for example, it fixes nitrogen into a form accessible by life.

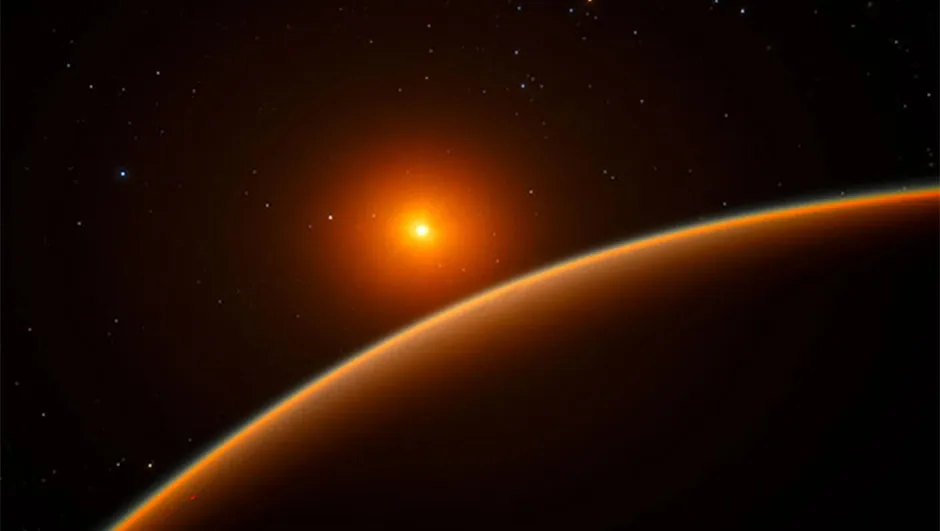

So what conditions might extrasolar planets need in order to also support such a GEC – an important consideration if we are to understand exoplanet atmospheres?

Christiane Helling at the University of St Andrews has been researching this question.

Many exoplanets are predicted to have layers in their atmospheres cool enough to condense cloud particles, which also presents the possibility of lightning storms.

But some of these atmospheres are very alien – some exoplanets orbit their host star so closely that their surface is molten magma and the cloud particles are a mix of solidified minerals.

In general, Helling concludes that gas giants, or the super-Earths that are completely overcast, may not be able to support a fair weather current and so would have no GEC like Earth’s.

Other exoplanets, where one side is permanently facing their star, would be so hot on their daylight side that nothing can condense as a liquid, and clouds are only possible on the night side.

But a fair-weather current might persist on this day side, with lightning in the cloudy night side, and so planets with this hemisphere-by-hemisphere separation may develop a GEC on a scale far larger than Earth’s.

Characterising these processes is important for our understanding of the atmospheric dynamics on exoplanets, and which worlds might experience truly epic thunderstorms.

Lewis Dartnell was reading Lightning in other planets by Christiane Helling. Read it online here.

Prof Lewis Dartnell is an astrobiologist at the University of Westminster. This article originally appeared in the December 2019 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.