Humans are unlikely to ever set foot on Venus’s surface.

The extreme and relentless oven-like temperatures and chokingly thick and toxic atmosphere would be deadly to us, and all life as we know it.

Venus's atmosphere is hellish. Yet the idea that life might be found on the surface of Venus was once a popular one.

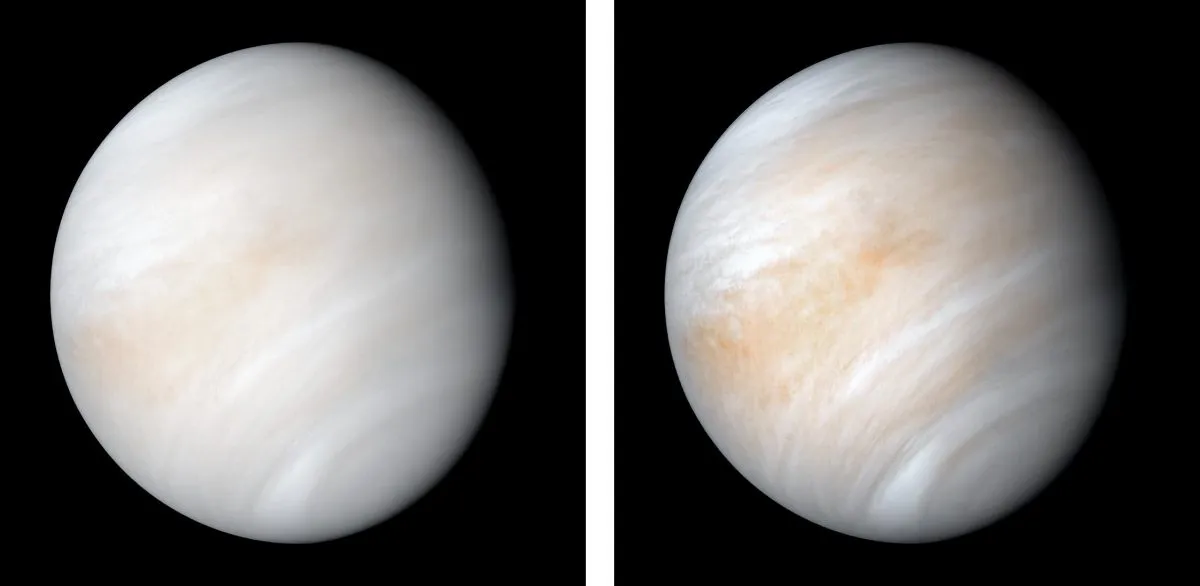

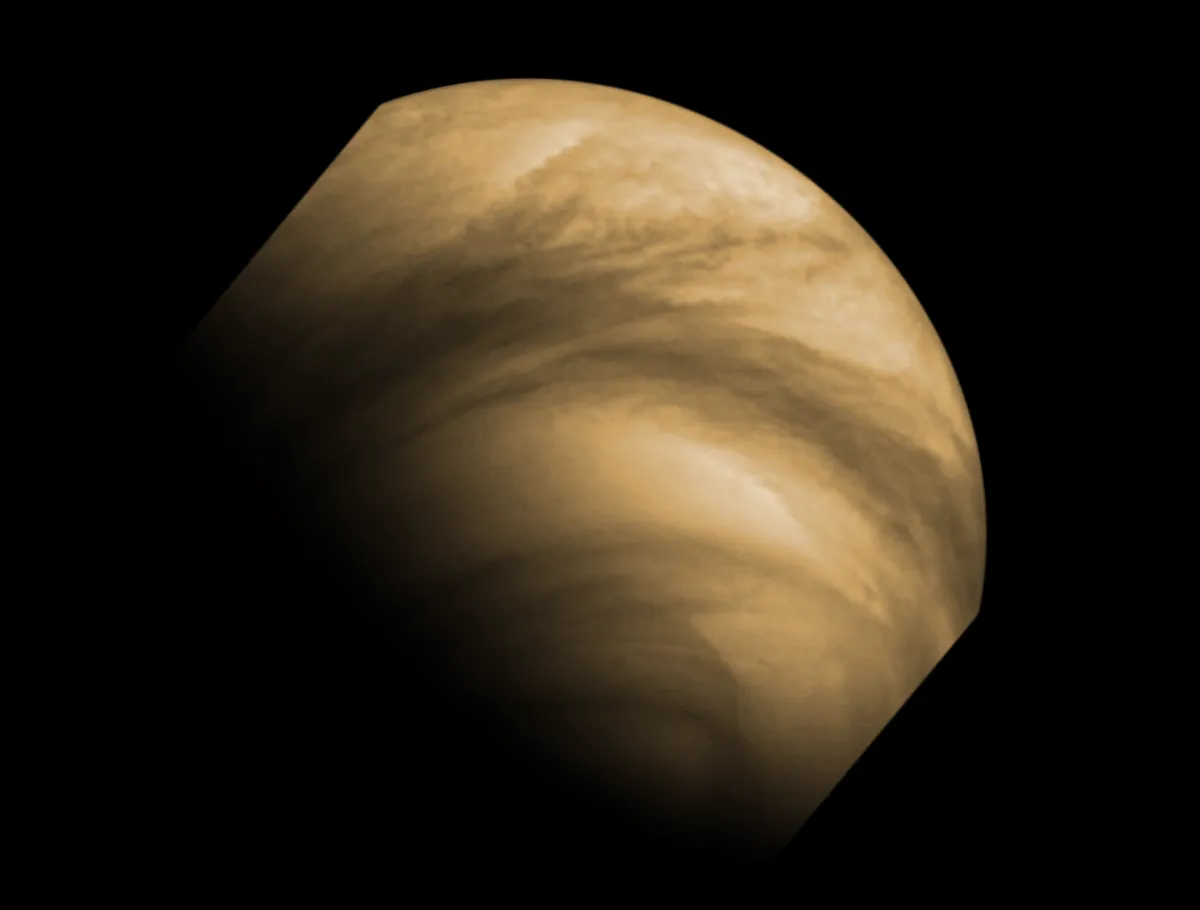

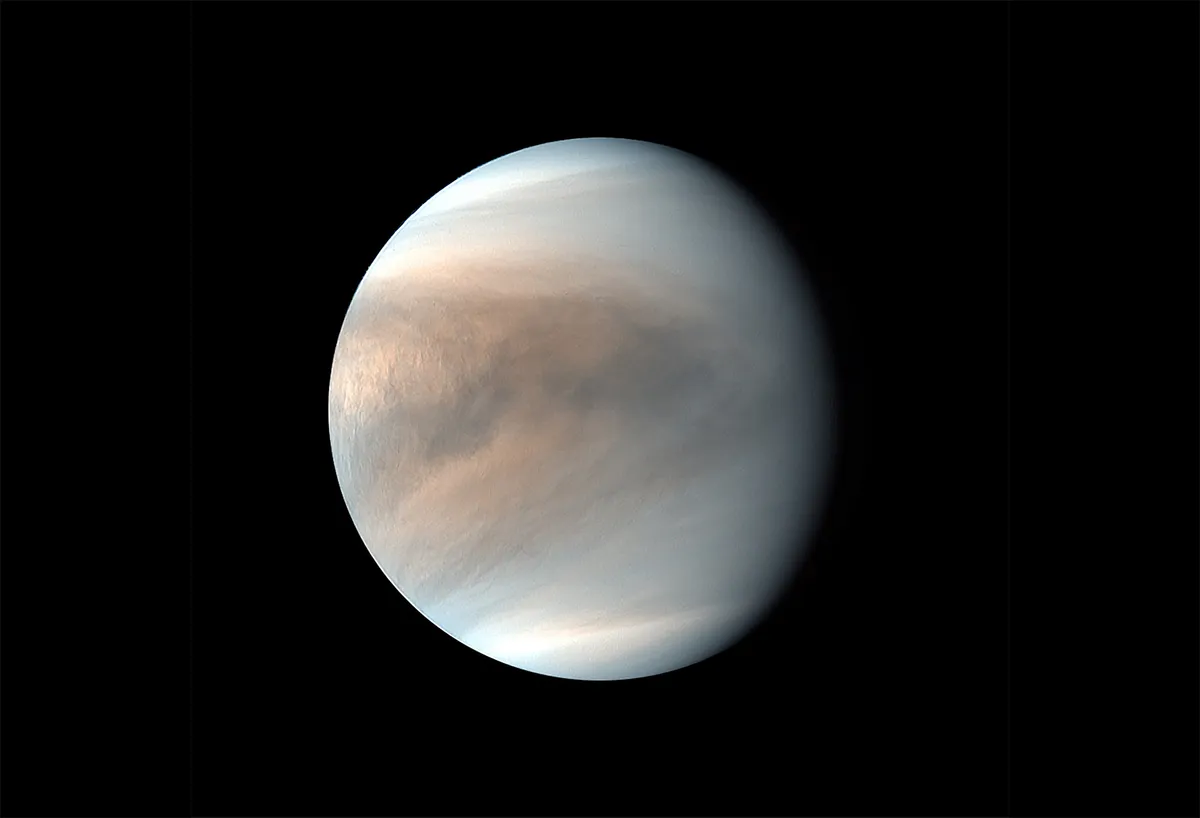

Venus is the second-brightest object in our night sky (the first being the Moon), but despite this accolade, when looked at through a telescope, it is underwhelmingly featureless.

Early views of Venus

The entire surface is hidden from view by a thick and permanent blanket of cloud which left scientists of the early 20th century with little way of knowing for certain what lay beneath.

Chemist and Nobel prize-winner Svante Arrhenius (1859–1927), for example, believed the clouds were made from water, just like clouds on Earth and, that being the case, the surface of Venus must be extremely wet.

Given that water is a primary requirement for life as we know it, Arrhenius further postulated that Venus was a swampland covered by vegetation.

Rather unsurprisingly, science-fiction writers from the time reflected these views, not only setting their stories on a Venus covered by swamps, jungles or even islands on a global ocean, but populating them with a variety of Venusian creatures and even, in some cases, humanoids.

Despite not being able to see the planet’s surface, astronomers were able to investigate the composition of the atmosphere through spectroscopy – splitting the light from Venus (reflected sunlight or thermally emitted by it) into its component wavelengths, and studying emission or absorption features created by the light’s interactions with the different molecules present there.

If Arrhenius’s wet Venus did exist, then this would surely show clear evidence of abundant water vapour in those thick clouds.

Yet, by the 1930s only carbon dioxide had been identified.

Water was, and continued to remain, curiously absent, and theories of a wet Venus began to lose favour.

By the time of the Space Age, they had largely (though not completely) been replaced in both scientific and fictional texts with a dry, desolate, desert world.

What Venus is really like

NASA’s Mariner 2 was the first spacecraft to visit Venus, making measurements as it sped past in December 1962.

Venus has since been visited by another 29 spacecraft, each returning details of just how inhospitable the surface of Venus really is.

Its atmosphere is dominated by carbon dioxide and is so dense that it creates crushing pressures at the surface that are equivalent to over 90 times those found at sea level on Earth.

As if that weren’t enough, the average surface temperature is a scorching 464°C (867°F), making it the hottest planet in our Solar System.

While you might expect the night to offer some relief from the heat (especially when each night is equivalent to 117 Earth days – plenty of time to cool off), you won’t get it, as the atmosphere does an extremely effective job of trapping in heat and keeping the surface hot all over.

This is because the carbon dioxide it contains is a greenhouse gas, efficiently absorbing incoming and outgoing (emitted from the surface) infrared radiation, thus trapping heat and preventing the planet from cooling.

On Venus, it’s so efficient that the surface is around 400°C (750°F) higher than it would otherwise be.

Given that the Venera spacecraft, 10 of which soft-landed on the surface in the 1970s and early 1980s, were not able to survive more than a few hours, it’s safe to say Venus’s surface is an inhospitable place.

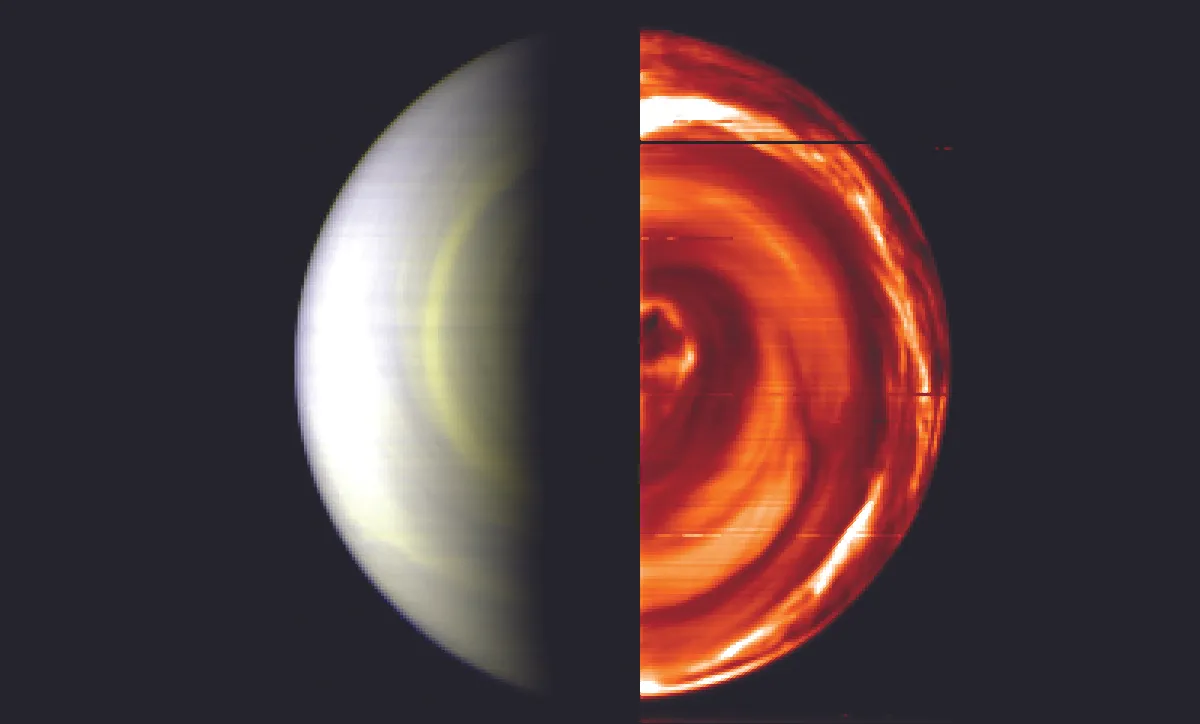

The permanent cloud deck shrouding Venus extends from around 45km (28 miles) above the surface to almost 70km (43 miles).

Despite being composed of sulphuric acid droplets, the range of pressures and temperatures found in these clouds are far more temperate than the surface conditions, leading some scientists to speculate that a form of microbial life may be able to survive there.

On Earth, it is well known that microbial life can become lofted into the atmosphere, although here they only experience a temporary excursion from the surface.

Could anything survive on Venus?

Louisa Preston, an astrobiologist at University College London’s Mullard Space Science Laboratory, notes that "just because the cloud deck on Venus could be habitable, doesn’t mean it is actually inhabited.

"And there would have to be some pretty hardy extremophilic microorganisms on Venus to be able to survive in it – ones that can survive in acidic conditions or have an iron- and sulphur-based metabolism, for example."

However, she also tells us that we should keep our minds open when we commence any search for life.

"There are undoubtedly many possibilities of extremophiles existing and thriving in ways we haven’t even imagined yet, and which could have the adaptations to survive this challenging environment."

Over the years, it has been suggested that such microbial life could be behind several currently unexplained characteristics of Venus’s atmosphere.

For example, the dark features observed in ultraviolet images of Venus could be explained if organisms are present that use (and thus absorb) these wavelengths as their energy source.

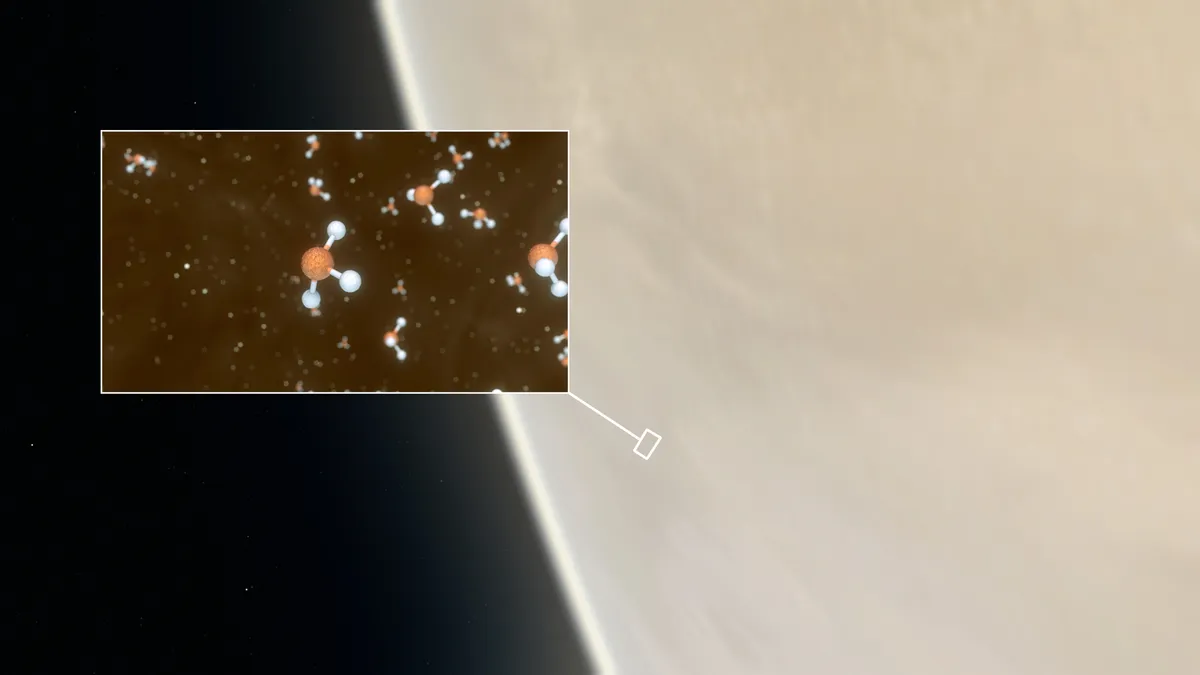

A tentative detection of the gas phosphine in Venus’s atmosphere in 2020 might also point to the presence of life, since phosphine on Earth is associated with life.

Since then, further studies have both confirmed and contradicted this detection of phosphine, with intense debate continuing to this day.

At the 2024 National Astronomy Meeting, it was also reported that ammonia, another molecule often linked to life on Earth, was also detected in the Venusian atmosphere.

Whatever the answer, finding phosphine is not definite proof of life being present in Venus’s clouds.

As Jane Greaves of the University of Cardiff, who led the report on the initial (and subsequent) detection of phosphine, explains: "We don’t know enough about how Venus’s atmosphere works to say exactly what rare gas molecules should be there, so there could be some purely chemical reaction making phosphine or ammonia."

Future missions to search for life on Venus

It’s clear that to definitively answer the question of habitability we need to send a mission dedicated to searching for evidence of life.

"We really do need to go there and drop a probe into the clouds," says Greaves.

"It could have instruments sensitive to chemicals being produced by organisms growing, or even be a microscope looking at droplets to see what’s in them!"

Currently, there are several missions dedicated to studying Venus being planned by space agencies:

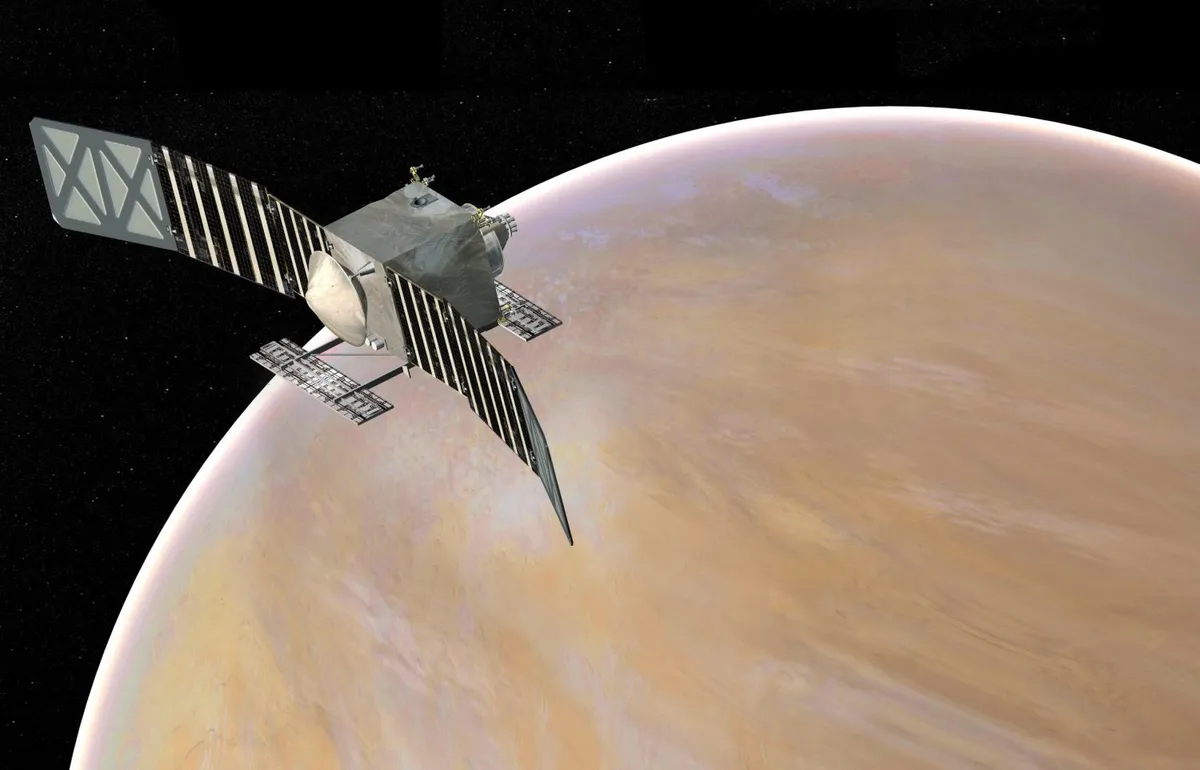

- VERITAS and DAVINCI (both NASA)

- EnVision (ESA)

- Venera-D (Roscosmos)

- Shukrayaan-1 (Indian Space Agency)

These aim to study the planet, its geology and its atmosphere, to understand how it became so different to Earth and whether it was once host to an ocean and even habitable.

All currently have scheduled launch dates beyond 2028, but there is another, private mission going there sooner.

Formerly referred to as the Venus Life Finder missions, the Morning Star Missions are a series of three spacecraft planned to investigate the Venusian atmosphere, measure any chemical biosignatures and determine whether it can or does support life.

The first, Rocket Lab Probe, is targeted for launch in 2025.

Upon reaching Venus, it will descend through the atmosphere, searching as it goes for the presence of complex organic molecules that could be related to life.

As Sara Seager, a planetary scientist at MIT who leads the Morning Star Missions, explains: "While it will not find signs of life, it is the first step in the process."

The spacecraft planned to follow, Venus Habitability Mission, will comprise a balloon which will fly among the cloud deck for one to two weeks, using a mass spectrometer to identify molecules so complex they may be associated with life.

Finally, in the further future, a Venus Atmosphere Sample Return spacecraft could bring a sample of Venusian atmosphere back to Earth, where it can be studied for signs of life, or even life itself, with far more complex instrumentation than we can put on a spacecraft.

While we wait for these missions, work is already underway in laboratories here on Earth to investigate whether or not any of the chemical compounds significant to life might be able to survive in the sulphuric acid clouds of Venus.

Seager tells us that her team "has found our 20 biogenic amino acids (with one exception) to be stable in concentrated sulphuric acid, with half being chemically modified."

Furthermore, "nucleic acid bases are stable" and "some lipids we tested can form tiny cell-sized spherical vesicles as they do in water".

These results suggest that more chemistry is possible in these sulphuric acid clouds than was once thought.

So all bets are off when it comes to predicting whether or not these future missions will find life around Venus.

Do you think we'll find life on Venus? Should we send spacecraft to such an inhospitable place? Let us know your thoughts by emailing contactus@skyatnightmagazine.com

This article appeared in the December 2024 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine