Does Earth have rings? As is so often the case in astronomy, this is one of those seemingly simple questions that actually has no simple, obvious answer.

Or at least, not one that tells the whole story, because there IS, of course, a simple, obvious answer readily available – that answer being no, Earth doesn't have rings.

For proof of that, just look up! Were Earth encircled, like Saturn, by rings of rock, ice and dust, you’d expect same to be visible with the naked eye at least some of the time… but there’s nothing there.

Discover more about our planet with our guides Why is Earth called Earth, How old is Earth, pictures of Earth from space and our guide to Schumann resonances, Earth's 'heartbeat'

Why do planets have rings?

We know planets do have rings. Saturn has rings. Jupiter has rings.

The James Webb Space Telescope captured an amazing image of Uranus's rings, and Webb even captured distant planet Neptune's rings.

J1407b is the first exoplanet discovered with rings.

Why some planets DO have rings is still a matter of some debate.

Some astronomers argue that Saturn’s rings are made of leftover material from the Sun’s protoplanetary disk that, for whatever reason, was neither drawn in by gravity to form the planet itself, nor to form a satellite in orbit around it.

A second theory suggests that the matter that makes up Saturn's rings did once form a moon, but that moon then disintegrated, either pulled apart by tidal forces from its host planet or smashed to smithereens in an impact by a comet or asteroid.

Either way, what we do know is that so far, it seems to be only gas giants that have rings, while rocky planets like Earth don’t.

Again, why this should be the case isn’t entirely clear: it may be something to do with gas giants’ much greater size and mass.

Or it may be connected to the fact that the gas giants formed at the Solar System’s outer limits while the rocky planets formed much closer to the Sun.

Did Earth ever have rings?

Whatever the cause of this observed phenomenon, you wouldn’t expect Earth to have rings.

And it doesn’t, although some astronomers who challenge the received explanation for the formation of the Moon (in which Earth was hit by a large, putative object called Theia) have suggested it may instead have coalesced from a ring of debris that was the result of not a single but multiple impacts.

So Earth may have had a ring or rings at one time – but it could also be argued that it has rings now.

Earth's space junk rings

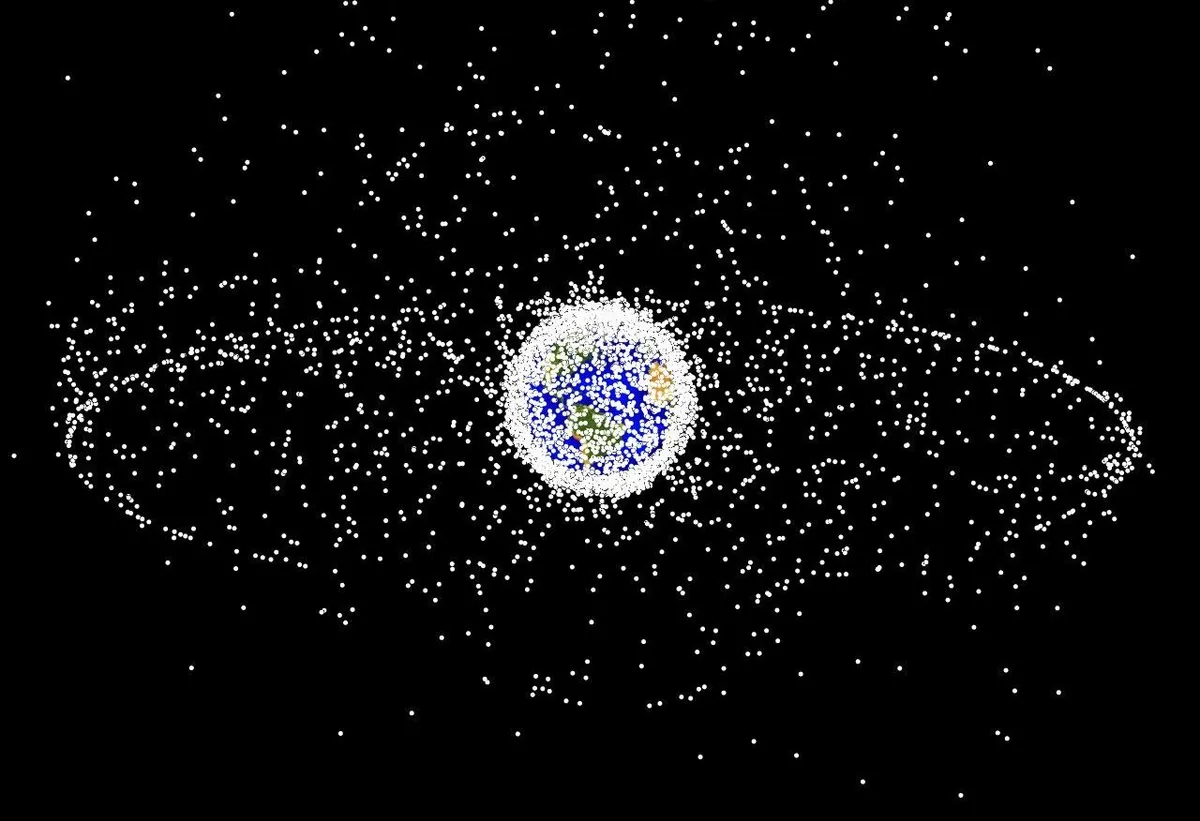

Over the course of the past 60-70 years, humanity has been busy sending out spacecraft to explore the Solar System, while putting several thousand satellites into orbit around Earth.

These satellites themselves form a ‘ring’ of sorts around a planet, while another has formed from all the small pieces of debris that those satellites and and spacecraft have strewn in their wake – a loose bolt here, a few flecks of paint chipped off by a micromeorite impact there, right up to larger items such as a spanner dropped by an astronaut during an EVA.

This ring of space junk isn’t visible, but it’s there around Earth.

NASA can track objects roughly the size of a softball and up, but such objects constitute less than 1% of the estimated 170 million pieces of debris that are in orbit around our planet.

And that’s a problem, because these objects are whizzing around Earth at an orbital speed of 35,400 km/h (22,000 mph), and any one of them could do serious damage to any spacecraft that it might crash into.

That’s something US scientists should probably have thought about in the early 1960s when they set about attempting to put a human-made ring into orbit around Earth deliberately!

Project West Ford

Project West Ford was an attempt by the US, at the height of the Cold War, to fortify Earth’s ionosphere – the layer of ionized hydrogen and oxygen that radio signals bounce off – as a means of guaranteeing reliable radio communications, in the event that undersea cables might be destroyed by the Soviet Union or its allies.

To do so, scientists proposed putting into orbit nearly half a billion tiny copper antennae – each just 1.78 cm (0.7in) long and, with a diameter of just 17-25 micrometres, no thicker than a human hair.

Indeed, attempts to do just this were made in 1961 and 1963, but the first failed.

The second saw some success – with radio signals successfully bounced off the new artificial ionosphere – but was swiftly abandoned following an outcry by non-US scientists, who quite rightly protested this deliberate pollution of our planet’s immediate environs (“USA dirties space,” read one headline in Soviet state newspaper Pravda at the time).

Most of the needle-like antennae launched in 1963 have since fallen back down to Earth but some are up there to this day, clumped together in balls which number among the pieces of space debris that NASA is, as discussed above, tracking closely – and that form what is as close to a ‘ring’ as Earth can currently be said to have.