Binary craters, also known as double craters, are something of a curiosity.

They’re much more than two craters that happen to have formed side by side.

Instead, double craters are believed to have been created simultaneously by the impact of a binary asteroid – a larger body being orbited by a natural satellite.

About 15% of all small asteroids are believed to be orbited by their own little moon, so dual craters, formed by the impact of both an asteroid and its moon at the same time, are actually relatively common.

Double craters and binary asteroids

As such, double craters can also tell us something very useful about the population of binary asteroids.

Binary asteroids in space are currently detected directly using radar, but this is only possible for the closest, near-Earth asteroids.

They can also be inferred from a periodic change in their brightness, measured by telescope observations.

But this only works well for binary asteroids with a small separation from each other, and the moon needs to be orbiting edge-on to Earth.

So these observational techniques suffer from significant biases in the sorts of binary asteroids they’re able to find.

Looking at binary craters formed when these twinned asteroids impact on planetary surfaces, however, reveals more information on the population of binary asteroids in the Solar System.

A recent study of Mars, for example, found 150 examples of binary craters.

Studying double craters

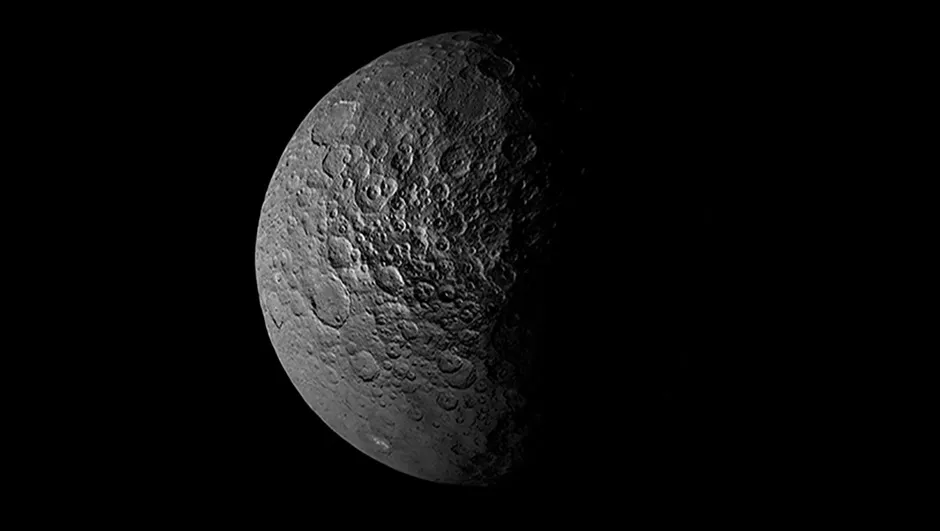

One study into double craters focuses on the surfaces of the two largest asteroids, Ceres and Vesta, which have been photographed and mapped at high resolution by NASA’s Dawn probe.

The team – led by Carianna Herrera, at the time a Masters student at Université Côte d’Azur, France – began with databases of almost 45,000 craters on Ceres and almost 12,000 on Vesta.

They looked for close-by craters that appeared to have formed at the same time, based upon the presence of a straight wall where the neighbouring craters contact each other, and upon the absence of signs that ejecta from one crater has partially filled the other.

Pairs of craters where one is visibly less well preserved, and therefore significantly older than the other, were also ruled out.

The team identified a set of 39 binary craters on Ceres and 18 on Vesta.

Then they studied the parameters of these binary craters, such as the separation between the two and the inferred sizes of the original impactor and its satellite.

They found these parameters to be similar to those found for binary craters on Mars.

But importantly, these binary-crater-forming objects are very different from the binary asteroid population known from observations.

The craters on Ceres and Vesta (and also Mars) indicate binary asteroids where the partners are roughly equal in size and relatively separated.

As we saw above, due to observational biases, the binary asteroids detected in the Solar System are often pairs significantly different in size and in a close orbit around each other.

And so the double craters studied by Herrera are the footprints left behind by objects that have long since vaporised.

They reveal a population of asteroids that has not yet been observed in space.

Lewis Dartnell was reading Binary Craters on Ceres and Vesta and Implications for Binary Asteroids by Carianna Herrera et al. Read it online at: arxiv.org/abs/2405.18460

This article appeared in the September 2024 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.