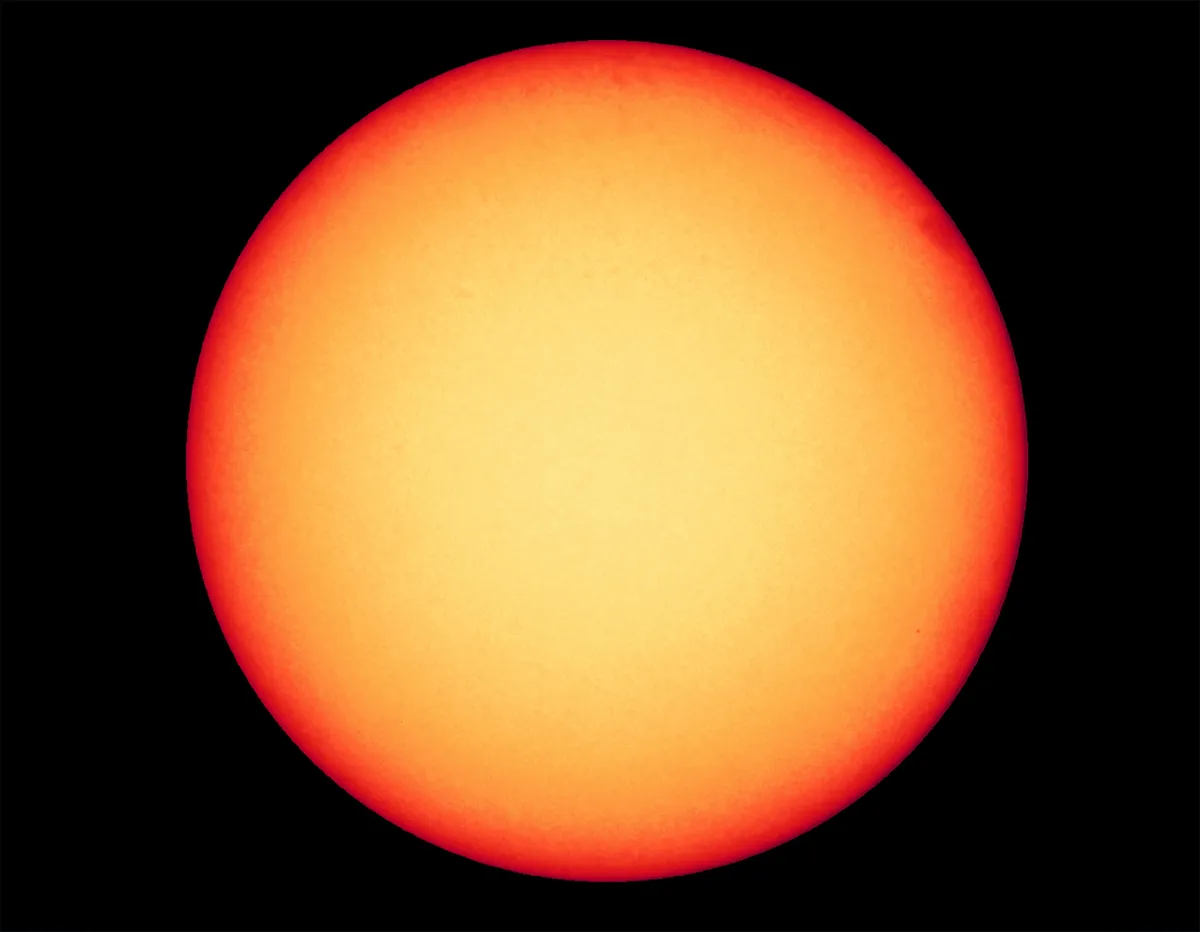

The European Space Agency has released the first images captured by its Solar Orbiter spacecraft, revealing unprecedented close-up views of the surface of our Sun and enabling solar scientists to analysis phenomena never before seen in such detail.

Solar Orbiter was launched on 10 February 2020 and carries 6 separate telescopes to image the Sun, plus 4 instruments to monitor how solar activity affects the environment in which the spacecraft is orbiting.

Comparing data from both sets of instruments allows scientists to learn more about the solar wind, a stream of charged particles that emanates from the Sun and whose influence is felt across the Solar System.

More on Solar Orbiter:

- Read our interview with mission scientist Pro Richard Harrison to find out how Solar Orbiter will study the surface of the Sun

- Find out about Solar Orbiter's journey in our expert guide written by space engineer Helen O'Brien

The images were captured using Solar Orbiter's Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) instrument on 30 May 2020, when the spacecraft was about halfway between Earth and the Sun.

This put it closer to the Sun than any other spacecraft before and allowed the study of features just 400km across. Solar Orbiter is due to get even closer as the mission progresses.

Solar Orbiter spots ‘campfires’

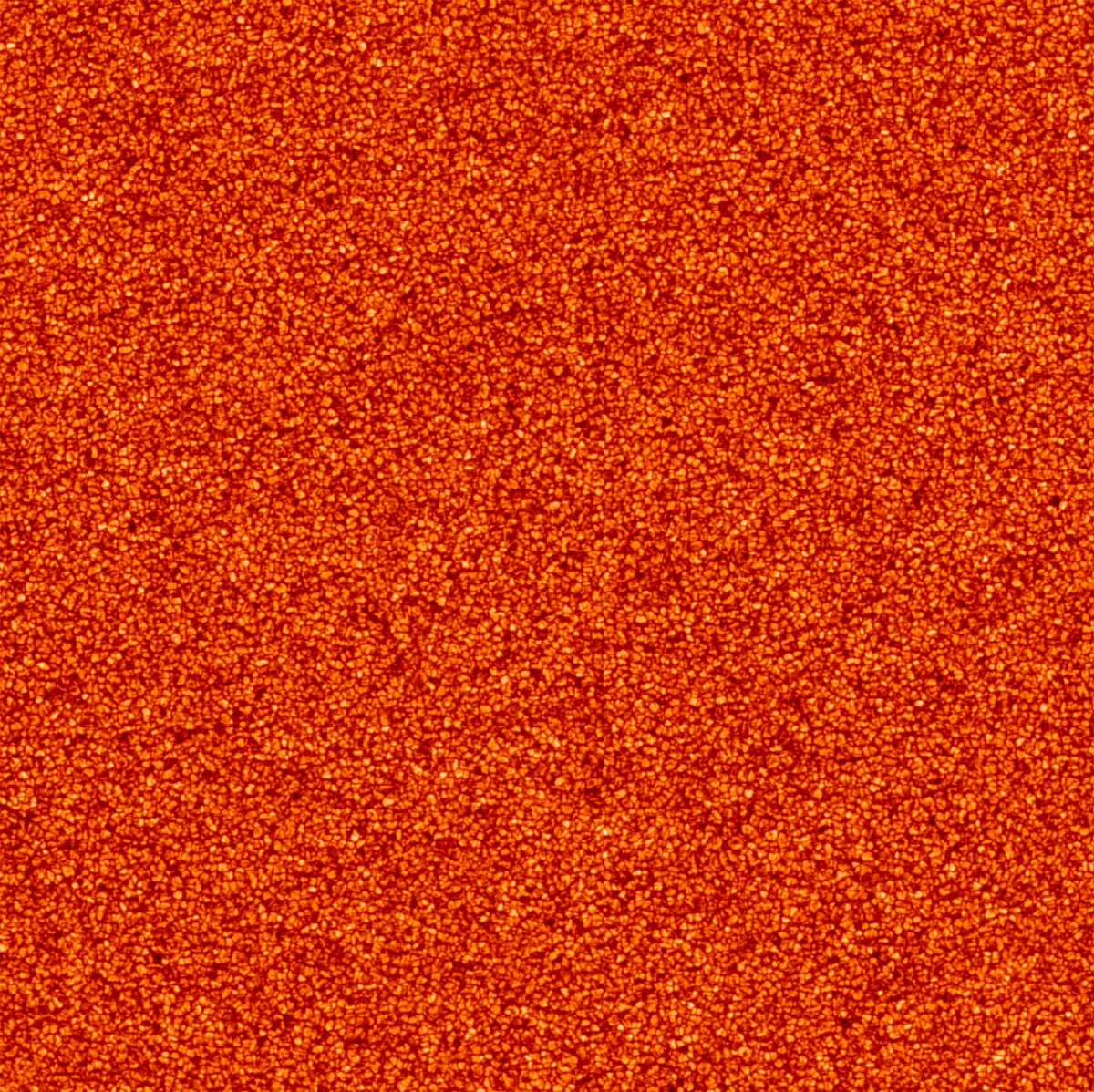

Solar Orbiter scientists have pointed out so-called ‘campfires’ in the spacecraft’s new images. These are miniature eruptions on the surface of the Sun captured by from a distance of just 77 million km.

"The campfires are little relatives of the solar flares that we can observe from Earth, million or billion times smaller," says David Berghmans , Principal Investigator of the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) instrument that captured these images.

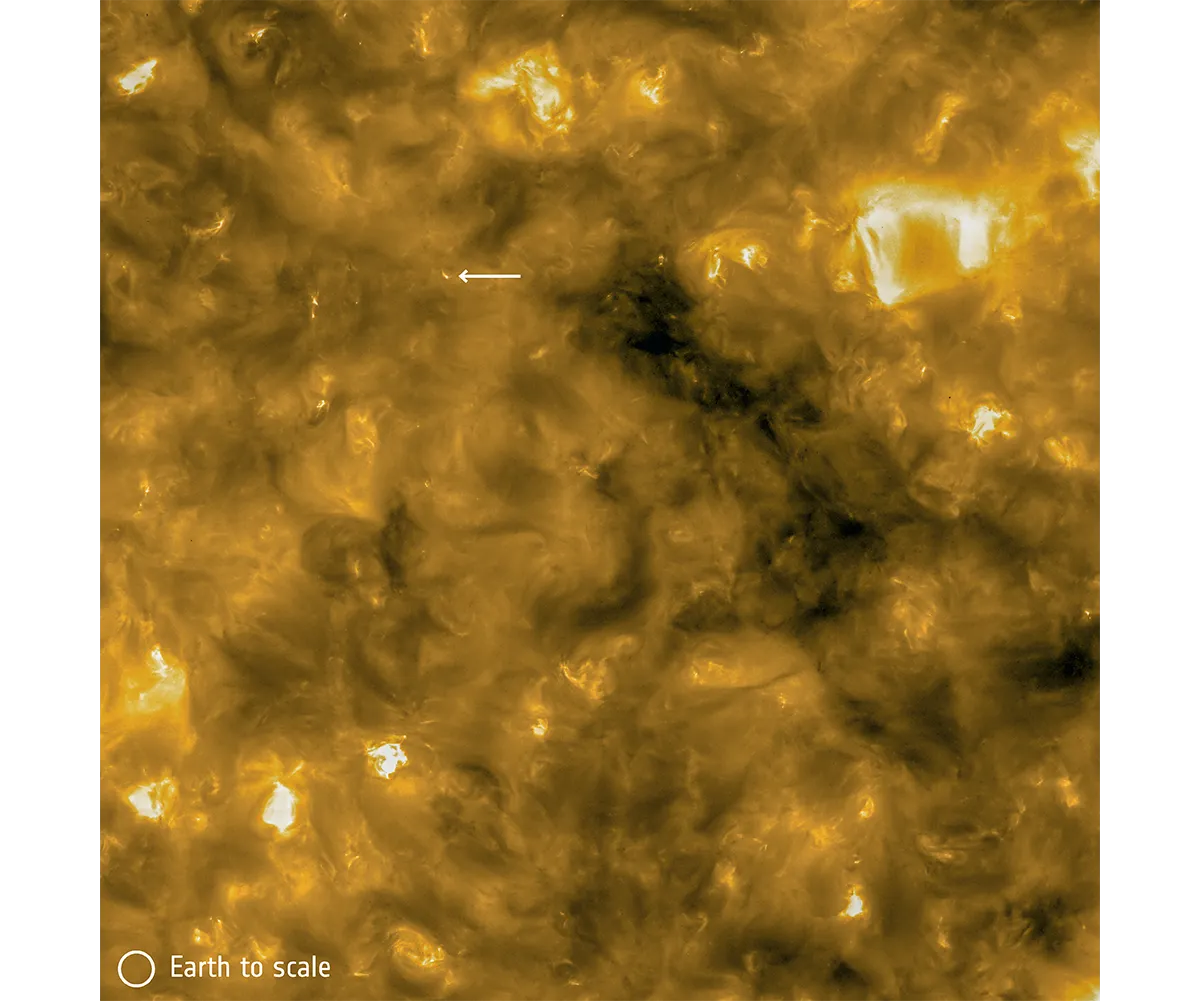

EUI takes hi-res pics of the solar corona, which is the outermost layer of the Sun's atmosphere and stretches millions of km into space.

The solar corona's temperature is over 1,000,000°C, much cooler than the surface of the Sun, which is 5,500°C.

Scientists are still unsure about the exact mechanisms that heat the corona, but Solar Orbiter's data could bring them a step closer to unlocking one of the biggest mysteries in solar science.

"The Sun might look quiet at the first glance, but when we look in detail, we can see those miniature flares everywhere we look," he says.

"These campfires are totally insignificant each by themselves, but summing up their effect all over the Sun, they might be the dominant contribution to the heating of the solar corona," says Frédéric Auchère, Co-Principal Investigator of EUI.

Capturing solar flares

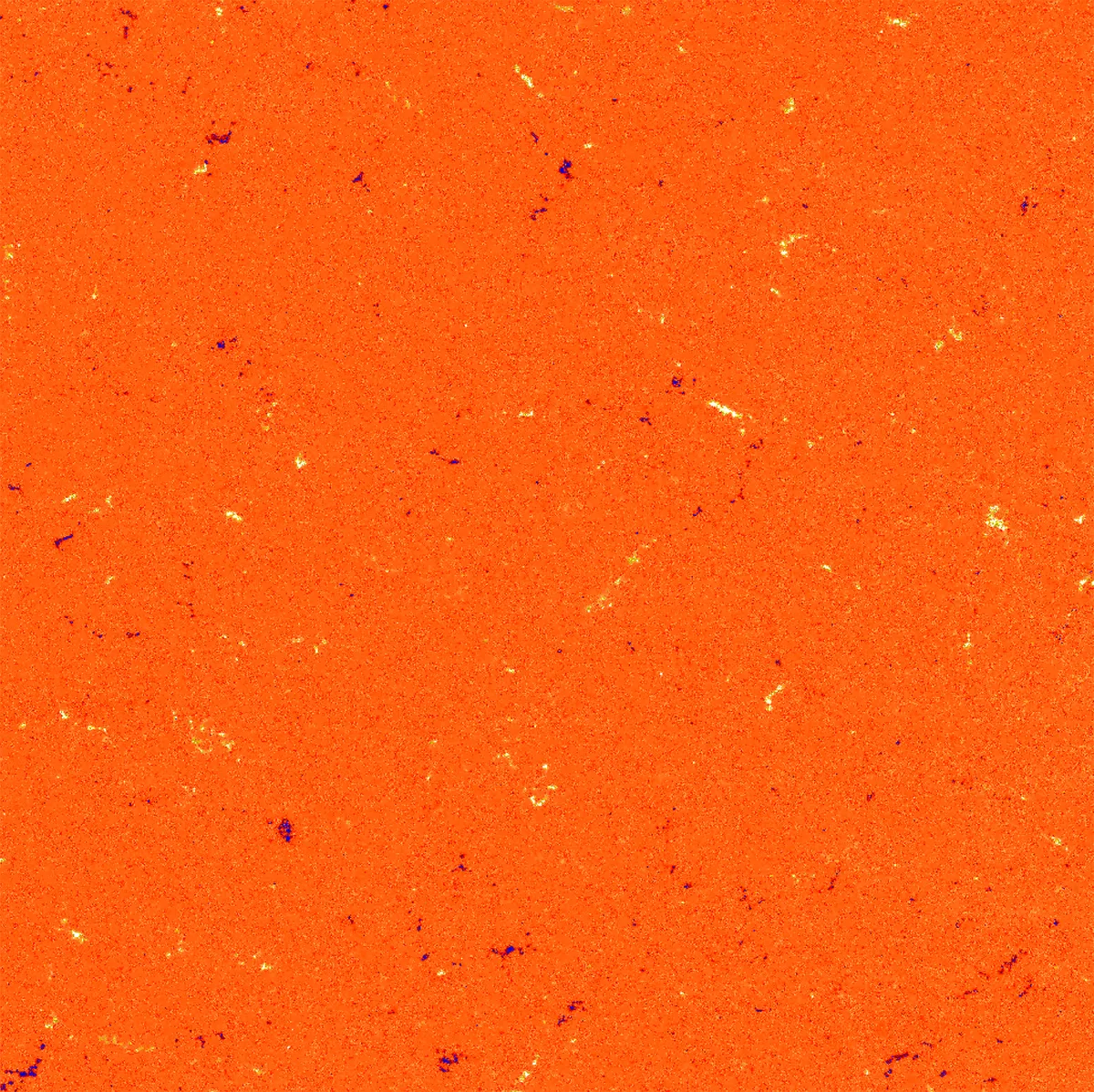

"Right now, we are in the part of the 11-year solar cycle when the Sun is very quiet," says Sami Solanki, Principal Investigator of Solar Orbiter's Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager (PHI) instrument.

For more on this, read Lucie Green's guide Understanding the Sun: the science of the solar cycle.

"But because Solar Orbiter is at a different angle to the Sun than Earth, we could actually see one active region that wasn’t observable from Earth. That is a first. We have never been able to measure the magnetic field at the back of the Sun."

The PHI measures the magnetic field lines on the surface of the Sun and can monitor active regions with strong magnetic fields that may produce solar flares.

During a solar flare, a burst of energetic particles emanates from the Sun into surrounding space.

These can even impact on life on Earth, interacting with our planet's magnetosphere and disrupting power grids and telecoms.

Analysing the solar wind

Solar Orbiters instruments are also able to analyse and characterise the solar wind as it passes the spacecraft, in situ.

"“Using this information, we can estimate where on the Sun that particular part of the solar wind was emitted, and then use the full instrument set of the mission to reveal and understand the physical processes operating in the different regions on the Sun which lead to solar wind formation," says Christopher Owen, Principal Investigator of the orbiter's Solar Wind Analyser.

"We are all really excited about these first images – but this is just the beginning.

"Solar Orbiter has started a grand tour of the inner Solar System, and will get much closer to the Sun within less than two years. Ultimately, it will get as close as 42 million km, which is almost a quarter of the distance from Sun to Earth."

Iain Todd is BBC Sky at Night Magazine's Staff Writer.